|

Pray don't talk to me about the weather, Mr. Worthing. Whenever people talk to me about the weather, I always feel quite certain that they mean something else. And that makes me quite nervous. - Oscar Wilde In the spring you can find our front door with your eyes closed. From the driveway, smell your way to the rose bush. A step or two later, pass between the narcissus blooms under the bird bath and the lavender, which has gone crazy since I planted it beneath the kitchen window box a few years ago. On the right, at the wall of blossoming jade, which started as a tiny clipping from the bush outside my former apartment, lift your foot for one, two, three steps. Here, open your eyes. Though you stand nose to twig at a wintery handmade wreath I found on Etsy a few months ago, there is no fragrance. I should probably find a new one for spring.

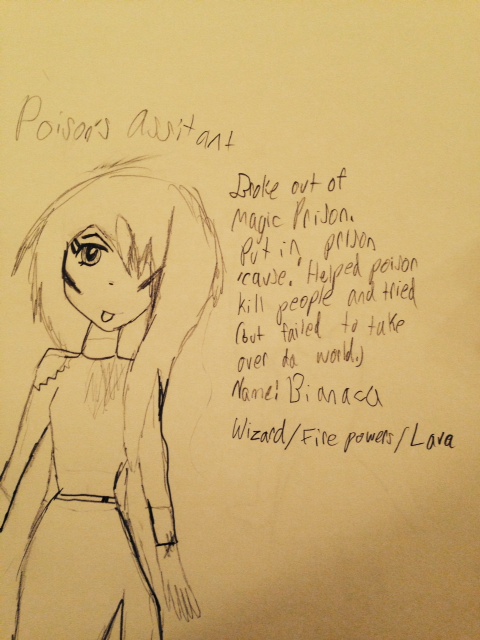

You'd better have a key ready, even if you hear voices clearly from within. Even if you knock, the door will not open without your effort. Even if you can report the very movie being watched on the other side. Even if you see through the window beside you the figure of a teenager as she passes from the living room through the dining room to the kitchen for a snack. You could try banging a hefty and frantic boom-boom, as she does every single time she comes home, but it's easier to just use your key. It's not as if you're in a rush: A whiff of orange blossoms floats over the roof from the backyard. Somewhere a finch sings. Inside, a barrage of new sensory input. The 13-year-old is in her chair three feet from the television, ten from the front door. You say "Hello!" in a cheery voice, imagining that perhaps she hadn't heard your car, your steps, the key. Her response is teenagery-dull. You pause for a moment to assess. The Matrix is on, 1, 2, or 3, you don't know (are there more?), but her head is bent over a sketch book. You attempt another greeting. "Whatcha watching?" as if you couldn't tell. "Whatcha drawing?" because sometimes she'll say. Maybe something radical like "How are you?" in another pleasant tone. The elements of simple communication that work so well with adults fall flat. "It's nice out this evening," you say, kicking off your shoes, knowing full well that she doesn't give a damn about the weather, the news, or connecting. I used to resent small talk. The low-hanging fruits of weather seemed only to pertain to the mindless, surface chatter of adults. It neither said anything nor did anything, I reasoned, and I suspect our 13-year-old feels the same, annoyed with the unsubstantial filler. There's an arrogance to her dullness. A judgement, I imagine, that raises her above petty niceties. Say something worthwhile or stop wasting my time. Like the writerly advice from Strunk & White: make every word count. Though she's more likely thinking, Just shut the fuck up. To her, I imagine small talk about the weather seems worth about as much as packing peanuts. Thirty gallons of the Styrofoam kind go for $9.27 at Walmart, so peanuts are basically worthless. Filler to brush away as you root around for the good stuff. Trash them or leave them to dissolve in the sink. They merely take up space and disappear. Like small talk. And yet, $9.27 is worth something, isn't it? People spend it gladly to cushion the good stuff. Olive oil. Porcelain. A vintage keyboard. Even our thirteen year old wouldn't think of shipping a delicate object unpadded to rattle around in a box, take every hit. I'm trying to think of something that's precious to her, an object to name here, but nothing comes to mind. She draws and writes, but appears to care little about anything else. Or this: she is precious; that gruff affect is her peanuts. The disdainful glances, dour responses. She's a newly-minted teenager, fresh out of childhood, en route to adulthood, jostled around at every bend. Her mood is her $9.27 of bubblewrap. It's the hard shell of chrysalid, because maybe she's gone completely to goo inside and needs a stern exterior to ensure her safety. It's scaffolding, because didn't you see the signs? Construction Zone! No trespassers! I get it as best as a forty-something-woman/former-girl with faulty memory can get it, but it's been a minute or two since I was thirteen. Thank the stars. Some day, when she's less gooey on the inside, I wonder if she'll see how stark the chasms can be between two individuals. How we've all been thirteen, all've been goo, but no two goos are the same, and how do we start from that? Humans might be a social species, but how on earth do two people who have been spinning in their own separate orbits all day long possibly begin to connect? Though I used to resent small talk, it's really kind of beautiful, isn't it? Those slender cords of niceties, weather. "Look at that rain": a rope thrown from one to another. It's a hefty job that a beautiful day commands. Wind, clouds, the jasmine in the air: Delicate as they are, their forces are greater than us. I don't know how your day is, nor do you know mine. So let's talk about the weather, enter carefully into each other's orbits, and look up at our shared sky. You drop your bags, prick your ears for the others. Music from the studio: Darby is working on a tune. A scrape on the stove: the 17-year-old is cooking. Meaty scents. It's hard to tell whose dinner, with vegetarian sausages lately so close to the real thing. You make your rounds greeting them, then duck into the bedroom for a quick costume change. The backdoor is open to the early evening. In an old Dr. Pepper bottle on the dresser, Darby's put a twig of orange blossoms, white blooms, green leaves.

0 Comments

"I have only to break into the tightness of a strawberry, and I see summer – its dust and lowering skies." - Toni Morrison, The Bluest Eye

July has gone too fast, but isn't it human to eke out just a little more before the last grains of sand fall? A third of July I spent in the northeast, teaching a week of songwriting in Allentown, PA for the International Women's Writing Guild's annual conference at Muhlenberg College, and then visiting friends in White Meadow Lake, NJ, a place where as a child I once lived. When I think now about the conference and weekend after with old friends, I remember stories and clouds. There was a slice, though, of three hours, west of both Allentown and White Meadow Lake, that comes to me mostly as water. It was raining, harder than a drizzle, lighter than a storm, when I parked on the soft shoulder in front of my aunt's house, not far off Route 80. Having packed in ever-sunny Los Angeles a week earlier, I didn't think to bring a rain jacket or hat. My uncle, who sat beyond the porch overhang, who's lived all his life (as far as I know) in the PA clime, didn't have one either. I don't remember us saying much, and we didn't mention the weather. The other water: My uncle made some coffee, I stirred in sugar; I dabbed at my eyes with a tissue from the coffee table at the foot of the yellow couch where I sat with my Auntie Dish, in an art-filled room I vaguely recalled from my childhood; my aunt dabbed at her nose, where the tube of moist oxygen made it feel, she told me, like her nose is always running. It's lung, she said, because I thought it was stomach, which she did have once, along with breast, thyroid, and colon. "The only kind nonsmokers get," she said, without bitterness. I asked her how she felt, thinking both of her, on the edge of something I'm trying to understand, and of my grandmother, who is my aunt's twin, who will be left behind. If learning is a thing we do in school, I never learned to read. I emerged from the womb with a book in hand, like it was a road map to figuring out this life. In the back seat of the Volvo, my head bent to cloth-covered Bedknobs and Broomsticks and A Wrinkle in Time, left over from my mother's childhood, and cornflower blue hardbacks of The Bobbsey Twins. When I was six, we moved in with my Grandma Roro and grandpa in the duplex where my mother had been raised with her two sisters and, on the upstairs side, her three cousins, children of Dish and my rain-immune uncle. The two families propped open the door between homes so the six kids had free reign, like the Bobbsey Twins on steroids. The next year we moved to White Meadow Lake, into what I have recently learned Californians like to call a "cabin." (As far as I can tell, a "cabin," by Los Angeles terms, is a regular house with amenities like a garage door and an attic, but situated on a mountain. Since White Meadow Lake is located in New Jersey, we called it a "house.") I would fall asleep in my upstairs corner bedroom, pretending that I was a twin and my other slept a mattress away. Though I didn't have my own real twin, I took some solace in the rumor that non-identical twins run in families. None of my friends could tell them apart, but everyone in the family knew that Roro and Dish were sororal twins, with nearly identical strawberry blonde hairdos. Maybe what I didn't have, my future children would. Meanwhile, I would play both parts: I would be beautiful like Roro (I was loyal to grandma) and smart like Dish (I'd heard Dish sat for my grandma's math exams in school). Grandma Roro and Auntie Dish were tall, with narrow waists and pleated pants. Each raised three children, though Dish had a boy. My mother was the first of that new generation, and when I came along, Roro and Dish were still young at forty-four, nearly the age I am now. They would sun themselves in the summertime wearing glamorous bathing suits, and I danced around swinging their vintage umbrellas, singing Singin' in the Rain. As I sat on the couch with my aunt, I asked her about a framed photo on the coffee table from around that time, a black and white of her and my uncle side by side, a bottle of champagne chilling in a bucket on the table. The oxygen tank hushed softly in the background, the rain fell forgotten outside. She told me they were on a Paris dinner cruise along the Seine, celebrating their twenty-fifth anniversary, and pointed to a painting on the wall behind the couch that they bought right from the painter on that same trip. "The paint wasn't even dry," my uncle said from his corner of the room. In case you've got a picture in your mind of Dish as an old lady half-unhinged and dying, I can do better. Dish is a great-grandma now. I started calling her earlier this spring, because I'd heard she didn't have much time left, and I'd realized how much had gone by. I didn't know her as an adult, only as I had known her when I was a child, and I wanted to. So I called, and we talked about the other generations, my cousins and their children. Dish made no distinction between her step- and biological great grandchildren, which warmed my heart. It's not that she didn't know the difference, but that she didn't care. Like how I feel about my kids, my step-daughters, they were hers either way. On one wall, I saw a photo of her and Roro when they were near five, which made me think of her mother, my great-grandmother, whom I loved, and who died when I was in twelfth grade. Were they close, I asked. Yes, she said, but paused. "You know what I wish," she said. "I didn't like that she was a racist. It made us all uncomfortable. She'd say shvartze, and not in a good way." We stayed for three hours on the couch, me asking questions as best I could, her answering as best she could. I wondered if there is any way for me, in this vibrant moment of my life, to fathom the way time crawls at the end. I thought of mothers-to-be, in the last weeks of their pregnancy, wishing the baby would just come already. Is it that way at the end, too? The bookends of life, slow, between which we love and fight and worry about bank accounts and career choices, and try to make some meaning out of the arbitrary event of our being? When we are born, we survive from mother's milk, and spend the rest of our living days eating from Mother Earth. Maybe at the end it's just waiting, waiting, waiting to go back home. Before I left, I asked how she felt. I meant body, but also heart and mind. She told me she's ready to go, not in pain at all, but ready. However, she's concerned that Roro hasn't yet accepted that her lifelong companion will be leaving first. In my twin fantasies, it had never occurred to me that, as at birth, one always passes through the barrier first. A few days after I saw Dish, I heard that she'd stopped eating. That was two weeks ago. Her body no longer needs to sustain. Soon, Mother Earth will feed off her. I hear the hospice nurse rearranged the living room, and Dish has a bed there now, and a rotating watch, made of her daughters, Roro and my grandpa, my mother's sister, and my rain-immune uncle. They recently did a genes test and found that all these 87 years everyone was wrong: Roro and Dish, it turns out, are identical. Makes sense, since identicals don't run in families, and they're the only twins on that tree branch so far. I've been trying to figure out if I should go back for the funeral, whenever it happens. I think of Roro, and want to comfort her. But I think, too, of my daily plans here. Of the syllabus I need to write; of the long and expensive airline flight back east; of my meager days off from work, already in the red, and of the David Wilcox songwriting retreat a few weekends from now; of the work I like to do and want to do, because it gives my life meaning between, as Joni Mitchell says, the forceps and the stone. By the time we hugged good-bye, because Dish and my uncle had a doctor's appointment and I was heading to White Meadow Lake to reconnect with old friends, tears had choked my throat too tight for me to say anything. If I could have, I would have said Thank you and I love you. I think she knows that. Of course it was pouring, too, because that's the way the east coast does weather: When you are saying good-bye to your great aunt for the last time, the clouds don't hold back. I closed myself in the rental car and let myself sob, and when I could see through my tears, I turned on my wipers and pulled onto Route 80 heading east. Type 1 Diabetes is an autoimmune disease, genetically associated with other diseases in that category (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, etc.), and renders an individual insulin-dependent. The pancreas, which otherwise works fine, stops producing beta cells that store and release insulin, a hormone which breaks down sugar from any kind of carbohydrate, whether simple or complex, and allows the body to use it for energy.

In the early months of 2015, as some of you know, our little one quickly got frightening skinny, was listless, insatiably thirsty, got up every two hours at night to use the bathroom. She was skinny because her body was starving and consuming all her body fat -- it couldn't process the sugar from food and use it for energy. She was listless because the brain depends on energy from sugar to properly function. She was thirsty because her blood sugar was way too high, and her body was trying to flush out the toxins. She had to pee, because she was drinking too much water. She couldn't sleep because she was in 5th grade and concerned she'd wet the bed. Her diagnosis, done easily with her pediatrician's prick of the finger to test her blood sugar levels, kicked off a full day of tests and T1D education for her and her four parents at Los Angeles Children's Hospital. She was pale, weak, frightened, and henceforth, until transitioning to an insulin pump later that autumn, on a every-three-hours glucose testing regimen (day and night) and 7-10 insulin shots a day. In equipment terms, that's 7-10 syringes daily, two types of insulin in two different vials plus backup in the event of emergency (e.g. earthquakes), 8-16 testing strips daily, alcohol swabs, a glucose testing monitor, many doctor visits, glucagon and an emergency kit in case she passes out from low blood sugar and can't ingest juice or another simple sugar by mouth. Since that autumn, she no longer needs regular shots because now she has a catheter with an inset stuck to alternating hips, changed every three days. The inset connects directly to a pump that looks like a pink pager hooked to the waistband of her clothes. Since the insulin is a constant drip, she doesn't need shots anymore in the arm or thighs, but we still have the back-up syringes in case the battery-operated pump fails. None of this addresses the depression that she entered the day she was diagnosed and didn't come out of for most of the year. Nor does it take into account the missed school days, because she was exhausted from bouncing blood sugar levels as the doctors tried to find the right ratios, and the public schools in our town, due to tight budgets, all share a nurse, who was only at her school periodically, and our girl was frightened that no knowledgeable adult was there to consistently help in case she needed it. It doesn't address the fact that she *did* need it, and so frequently just stayed home, and now, though money is tighter, goes to a Waldorf school with a class size less than a third of her public class, even with combined grades. It doesn't address how, for most of that first year, she didn't know how to eat because food was both necessary and a poison to her body. It doesn't address the mindless waiter who, just last week, brought her a regular Coke instead of diet, which shot her blood sugar sky high. And it doesn't address the lifetime of medical care and equipment that she will need just to manage this disease, to keep her healthy as she is right now, due to medical research, technology advances, JDRF advocacy and education, and Dr. Fisher and her incredible team at Children's Hospital Los Angeles. But, it does address the recent House vote to repeal and replace Obamacare with a system that does not protect those with previously diagnosed conditions, like T1D. If you know someone with T1D --- for example, our girl, now 13, --- consider sending this letter, which asks Congress to Consider Type 1 Diabetes Patients when the Senate looks to Reform the American Healthcare System. Feel free to use any of our story as part of your letter. https://www2.jdrf.org/site/Advocacy?cmd=display&page=UserAction&id=458 http://www.jdrf.org/press-releases/jdrf-issues-statement-opposing-revised-healthcare-legislation/ Last year, Shiloh's dad, her mom, her stepdad, and I spent Ash Wednesday with her at Childrens Hospital LA, because in the 6 weeks prior, this little one had become thirsty beyond words and had gotten too skinny too fast. She failed the easiest test in the world: a prick of blood from her finger. We found out that her beta cells had crapped out on their only job: to make insulin.

Ash Wednesday was day 1. Shy was paler than white as we learned how to administer the insulin shots that she'd need 6-10 times daily. A dietitian who looked like she needed a dietitian showed us with dirty rubber food toys how to measure carbs for a kid who'd never heard of the Atkins diet. A kind nurse who showed us her pregnant belly and told us that she'd been diagnosed with Type 1 Diabetes when she was 13 drew pictures on a white board of beta cells and sugar molecules and charts with arrows that pointed to optimal blood glucose levels. Only later, I realized why many of the hospital staff had smudges on their foreheads. I don't know much about the holiday except that it comes after a time of carnival, filled with carbohydrates that we, as of that day, needed to count carefully and measure in ratios of 1:14, 1:17, 1:15 against the insulin that, we were shown as Shy folded over the waistband of her pants, would be injected into whatever fat we could find on her skinny little body. That night Darby and I went home and drank a lot of wine because Shy went to her mom's house for the first night with T1D. The next day, she didn't go to school, or the day after, or many of the days -- 40%, perhaps? -- of the rest of the school year. She stayed with her mom for those first few nights. Darby spent the days over at his ex's house, the first time he'd had to spend so much time with her since 2006 when they realized that they didn't like spending so much time together. I, the stepmother, didn't go. Instead I went crazy at home wanting to see my sick kid who is another mother's kid. When Shy came back to our home, the every-three-hour blood sugar tests started. Darby took midnight, I took 3 a.m. Eventually Shy learned to sleep through them as we swabbed her finger with alcohol and pressed the tiny needle till a drop of blood squeezed out. In those first few weeks, she was starved -- literally. Her body had been starving without insulin to process the energy-giving sugars from food. She watched the clock and asked for a snack or meal every two hours, plates full of food. We shot her with needles and her spine and hipbones softened, but Little Miss Sunshine now had a body that no longer worked in concert with her mind. She fell into months of depression, angry at the new normal, questioning mortality, wishing she had not been born. Her older sister felt scared, at first, and then angry at how we all stood in the kitchen with calculators, adding up a cup of cereal and five strawberries and a quarter cup of soy milk, and how many carbs do you think this banana has, anyway? We pulled the insulin through the syringe while Rose had a tantrum because she was trying to tell us about something that happened at school, and Shy had a tantrum because she was sick of always getting shots, especially the ones at night that stung so bad we couldn't understand. We set the timer on our phones and Shy listened to her stomach grumble and watched Roo eat whatever she found in the cabinet, as she waited 15 minutes before eating the cereal and strawberries. By then she was hungrier than she thought she'd be, or not hungry enough to finish, but she'd already received the insulin and so had to eat exactly what was on her plate. Shots and finger pricks and tantrums and carb counts, Easter and her 11th birthday and then September came and the doctor called to say that on Rosh Hashanah we should all come to Childrens Hospital to learn how to use the insulin pump. On the Jewish new year, a nurse taught us how to insert and change the catheter every 3 days that would replace the syringe shots. The pump was hot pink, chosen by Shy for its color, which, we realized later, matched her school backpack and Luna Lovegood Halloween costume. We wanted to love the pump, but the insulin-carb ratios were wrong, and we didn't know that when Es fell into another depression, barely noticeable because she'd not really come out of the first one, it was due to her blood sugars riding too low. Though she tried to smile, she sat on the couch for most of our wedding celebration in September, didn't have cake, couldn't enjoy the company of the other kids. A few weeks later, the doctor adjusted the ratios and we saw the light come back to her eyes, the roses return to her cheeks. In her latest photos, you can see her new medical alert bracelet -- she went through three or so, but they all broke. The pump is clipped to the top of her pants. I'm now looking at a photo from a month after the wedding, 5 or 6 weeks after she got the pump, and one of the first days of smiling, which she does now frequently. Next week, instead of Childrens Hospital, we'll take her to Disneyland. She wants to celebrate a year since her diagnosis, which might sound strange to someone who hasn't witnessed her journey firsthand, but it's not strange to me. She should celebrate. She should be proud. These words don't really capture what Shy has been through, but though there's currently no cure for T1D, she has gotten through this grueling first year, and is healthy and thriving. We have a funny/aggravating situation at my house that should be filed under "tiny problems", but that is a problem nonetheless. Our side of the street is all single-family homes, but diagonally across is an apartment building with an unusual tenant theme: all tenants must own pets. Most, of course, have dogs, though I know of a few cat- and bird-only tenants there. The building doesn't have a lawn, so multiple times every day we see the dog-tenants out walking their dogs. It's a parade of all shapes and sizes, and we sit at our dining room table watching them go by through the front window. Irish wolfhounds. Pugs. Labs - golden, black. A beautiful St. Bernard that I want to hug every time. There's also a dog we call "the rat dog" who lives in the house on the north-side of our property and rarely has an owner accompanying his walks. Our lawn is the first accessible one the dog walkers encounter upon leaving their building. They make a beeline from their front door to our yard, let their dogs do their business, continue on. Most owners carry bags. Some do not. The rat dog, lacking opposable thumbs, an owner, and kind neighborly manners, does not even try. On the occasion that he is accompanied by our neighbor, she too doesn't try. Our lawn is a minefield. You never know where an unsavory sample has been deposited. We have tried different tactics over the years in an attempt to convey the message to our neighbors that we do not appreciate stepping in their unpleasant surprises. We've moved deposits from our lawn to the sidewalk, written messages in sidewalk chalk, offered bags to walkers, complained to everyone. Still, walking across our lawn (or simply getting out of a car) has been a gamble. This weekend we embarked on a new level of Operation Save-The-Yard. We could put in a fence, but we're plant-lovers, so we dug up a foot-and-a-half strip of lawn along the sidewalk and a bit up the sides as well, added paver bricks, planted a succulent garden and a few lavender plants, and fenced it all with a flimsy little roll-out fence that we'll probably take down when the plants grow taller. We still have the side between our house and the rat-dog's to border in lantana hedges, but meanwhile it's fenced off as well. All yesterday we watched from the dining room as canine by canine walked past our yard with nary a glance. One lady remarked, "Where will our dogs go to the bathroom if they can't get to your yard?" Hmmmm, we replied, as if we'd never considered the inconvenience to the dog walkers. It was two days of good work in between rain (and hail!) showers. We're proud of our work, so pleased with the way it looks, and so far, no rat dog to be seen. Poor south-side neighbors, though. Now theirs is the first available lawn... This piece first appeared in Lunch Ticket on February 20, 2015:

http://lunchticket.org/translation-truth-writing-kids/ Things look different from here, on the step/parent side of life. Every day the light shifts and something else is illuminated. Sometimes I write about my kids to understand what shifted, where the shadows now fall on the world, and what the light has revealed of my heart. However, this is not an essay about those light and shadowy things. It is about when the people we love and care for end up in the stories we write. It is an essay about the translation of thoughts to words. It is about the intersection of truth and compassion. Even in our native tongue, everything is an act of translation. Against all odds, we seek to bridge the gap of different life experiences, varied perspectives, divergent opinions, particular regional understandings, distinct cultural affiliations, restricted vocabulary, limited linguilism. Our individual differences are never-ending. It is a wonder we can communicate with each other at all, so we practice the art of translating our inner world into outer expression. We write our thoughts, striving to convey precise meaning. We hope that our intention is successful despite the probability that something will slip through the cracks. There are, after all, so many cracks between the conception of a thought and the delivery of a sentence. We seek to bridge the gap that lies between us, so we sit in a quiet room alone with a laptop or a stack of papers, or on a porch with crows cawing from the neighborhood-laced telephone wires, or in a café with the hissing milk-frother, the droning espresso machine, and the latest Damien Rice playing from the speakers. We mumble to ourselves, group letters and words together, rearrange them, erase, rewrite, start over. We stare into space with glazed eyes, the outlines of everything fuzzy, our ears deaf to the song refrain and the voices that drift through the semi-permeable edges of our thoughts. We are desperate to make sense of things. We must write, because the very act deepens our understanding of the chasms we seek to bridge. We explore and excavate with whatever tool we can find—garden shovel, fingers, cutlery, lover, children, parents—and keep digging through the superficial layers until we hit solid bedrock. Until we hit clarity. Until we find true self-understanding. I’ve been writing for a few years, maybe three, about my kids. They are not twins, but my two girls came into my life at the exact same moment, six years ago, just after the Thanksgiving pie. It was abrupt, joyful, strange, and like most births, painful. They say there’s no way for a first-time parent to prepare; I found this to be true. It is also true that with every birth of something, there is a death of something else. Don’t misunderstand: I love my girls, and I love my life. Still, I need to understand being an adult in this world, and being a parent from a stepmother’s perspective. I need to know myself in the light of that role. Writing illuminates. We parents and stepparents need to read other parents’ and stepparents’ narratives to help us through our own, but I’ve often wondered–do we have the right to write about our kids? Like so many other aspects of kids’ lives, they have little say in what we do, what we write. They are busy trying to make their own sense of the world, and have no voice to give consent to their place in our essays. As adult writers we have insight, but that insight is not necessarily a perspective the kids agree with. Even if they did, the kids do not necessarily want the details of their lives to be exposed to an audience of readers. But our capricious kids do not necessarily NOT want the stories shared either. Earlier this week, writer Andrea Jarrell explored her own thoughts on this topic in her Washington Post essay on writing about kids. In it she asked, “Why do I think my parents are fair game for my work, but I draw the line with my children?” Although Jarrell has chosen not to write about her kids for reasons she states in her essay, her question has led me to the opposite conclusion. Parents and guardians. Every day, with our best judgment, we make a million decisions weighing the kids’ needs and our own. We sign field trip permission slips. Medical authorization forms. Roller rink liability contracts. Oatmeal or Frosted Flakes? Bedtime early or late? Bath on Tuesday or Wednesday? Cell phone or no phone? Playdate or homework? We weigh the kids’ priorities against our own, and approve a Redbox rental of Frozen so we can finish an essay, an hour of games on the iPad so we can figure out ACA health insurance, a bartered cup of frozen yogurt for a quiet afternoon of income tax expense sheets. I write about the kids, but really I write about myself trying to make sense of where I stand now: in the kitchen with my ten-year-old making brownies as a Valentine’s gift for her teacher, or behind the camera taking photos of my fourteen-year-old whose boyfriend just pinned a corsage on her wrist for the Winter Formal, or at the barn next to the girls’ mother because on Sundays the riding lesson is the location for the hand-off that happens every-other-day between households. From this grown-up ground is where I write about my kids. Here, truth and compassion stand side-by-side. Digging for my own truth, my own self-understanding, I want the words I write to be as loving as every decision I make about my girls. There is a Tibetan prayer that I’ve said for years as part of my yoga practice. If I have a guiding light as I translate my inner world into words for others to read, this is it: May I be at peace. May my heart remain open. May I know the beauty of my own true nature. May I be healed. May I be a source of healing in the world. After the essays and stories and books are all written, I hope that my thoughts have been translated precisely. It is a long, long road from one heart to another. There are so many fault lines to cross. I always want my daughters to feel that the stories they’ve been a part of are honest, good, necessary, and loving. This piece first appeared in the literary journal Lunch Ticket on 23 January 2015:

http://lunchticket.org/one-night-strunk-white/ When my fifth-grader returned home Saturday after a week at Outdoor Science School, she brought a twine necklace strung with acorns and colorful beads, an endless stream of facts about the natural world on the mountain, and several riddles she learned from her counselors. Her week at OSS was the first time she’d been away from home, and so when she ran into the house she was overflowing with excitement about her first trip. The cabins (top bunk!); her meals (dessert every day!); the animals (baby frogs and a corn snake!); the owl pellet she dissected (a mouse skull and a shrew bone!). All day, until she was tucked into her bed and finally lulled to sleep by the tap-tap-tap of raindrops against the window pane, the house was filled with her lispy, delighted, never-ending anecdotes. I try to be an involved parent. I try to ask the kids engaging questions, encourage them to dig deeper into the events of their day, reflect back to them what they say so they can hear it for themselves, and then allow them to enhance or revise or elaborate. But on Saturday, juggling good parent practices with my overwhelming stack of spring semester work? Let’s just say that while she happily shared her OSS adventures, I alternated between listening and musing on the phrase “what you resist persists.” Open on the table in front of me lay Strunk and White’s The Elements of Style. I had resisted it since high school. That I have not ever read this slim volume is a bit hard to justify. It takes a day to read, and afterwards not much space on the bookshelf. It’s available for free online in pdf format. Most importantly, though, for an MFA candidate with an affinity toward writing, teaching, and editing, it’s an essential tool that cannot be ignored. Eliminate three out of those four--MFA candidate, writer, teacher, editor--and it is still necessary. When I recently began serving as Blog Editor here at Lunch Ticket, I realized I cannot continue to ride on my grammar and copyediting intuition. I need the vocabulary to explain my editorial suggestions. I need clear reasoning for my choices. I need cold, hard, plain, simple, black and white—Strunk and White--guidance. Dry, right? Elements of Style, though, is not as much about boring rules as it is intelligent advice. All writers of any genre need to craft clear, effective, engaging, bold sentences. Whether novelist, memoirist, or blogger, not having a handle on these tips is a liability. In E.B. White’s introduction, he quotes from Strunk’s principle #17 (omit needless words): Vigorous writing is concise. A sentence should contain no unnecessary words, a paragraph no unnecessary sentences, for the same reason that a drawing should have no unnecessary lines and a machine no unnecessary parts. This requires not that the writer make all sentences short or avoid all detail and treat subjects only in outline, but that every word tell. “That every word tell,” I reread several times. It is a compelling statement. With the drawing and machinery comparisons, it hits home. Unnecessary words and unfocused structure are part of the first-draft process, but a discerning reader can tell a first draft from a polished piece. First drafts hem and haw. They clear their throats and hesitate over ideas. They meander. A discerning reader—an editor, say—may wade through, but a non-discerning reader won’t spend the time traversing rough spots to mine the gems. They will simply move on to another story. Strunk and White’s statement is, in four words, an argument for careful revision. The Elements of Style provides the writer a checklist for that process. The book begins with basic punctuation and grammar rules that any writer should inherently know, followed by a list of composition principles I wish every blogger, essayist, reporter, memoirist, novelist--even Facebook poster, dare I suggest—would consider. Structure of the parts, and of the whole. Clarity of expression. Parallel construction of ideas. Economy of words. Verb tense agreement. While I scratched notes into the margins, my kid bounced off the couch. “Do you like riddles?” she asked, stopping her dance mid-twirl, arms spread out wide. At ten, truly, all the world’s a stage. She is an effervescent joy to our family. She has super powers, has been writing a book since third grade, and has well-timed, absurdist humor. It seems, while she has watched her older sister navigate teenage dramas, she dug her heels into childhood, determined to hang on to simple pleasures until life insists on the inevitable next phase. I can’t say if it’s her jokes or her giggles, but at least once a week we all--even the teenager--end up laughing till we’re in tears. Here’s one of the riddles she brought home from OSS: Q: One night, a king and a queen went into a castle. The next day, three people came out. What happened? A: One knight, a king, and a queen went into a castle. Obviously, the homophone is the key. Night/Knight. Half-listening to her and half-studying Strunk and White led me to consider this riddle from a craft perspective, and I found two other tricks within it that are meant to confound the listener. Sleight of hand is a puzzler’s prized tool, and a riddle’s only goal is to hide an answer in plain sight. When this teaser is spoken aloud, you can almost hear the lack of comma between “a king and a queen”. A serial comma, as I inserted in the answer above, further helps to reveal the three people who emerged from the castle. The most cunning tricks, though, are the most subtle. As I turned this teaser over, a topic covered in Part II of The Elements of Style came to mind. This is a principle Strunk and White call “express coordinate ideas in similar form.” They write: This principle, that of parallel construction, requires that expressions similar in content and function be outwardly similar. The likeness of form enables the reader to recognize more readily the likeness of content and function. Exactly contrary to Strunk and White, this riddle utilizes non-parallel structure to help mask its solution.One k/night is followed by a king and a queen. This use of non-parallel structure is meant to trick the listener. Until now I’d never dissected a riddle. I suppose if you are a riddler, you might consider using non-parallel structure as a tool to disguise the solution. For other writers, however, our goal is not to confound the reader, but to write as clearly as possible. We puzzle in our process so there is no confusion in our final manuscript. We should always strive to give a reader the clearest expression of our thoughts. For parallel structure, we would write one knight, one king, and one queen or a knight, a king, and a queen. Parallel structure. Clarity of expression. Concise writing. As my joyful kid twirled her way through the afternoon, and I made my way through The Elements of Style, I found myself siding with past teachers who once waved their copy of this book to the class. Anne Lamott writes in Bird by Bird, “the only way I can get anything written at all is to write really, really shitty first drafts.” She goes on: You need to start somewhere. Start by getting something--anything--down on paper… [But] the third draft is the dental draft, where you check every tooth, to see if it’s loose or cramped or decayed, or even, God help us, healthy. Another joke from OSS: The present, the past, and the future walk into a bar. It was tense. With all those mixed tenses hanging out together, I am sure it was. Luckily, this and other things are covered in a beautifully quick read: The Elements of Style. What, you don’t have a copy? Get a copy here (or wherever you like to get books), or download a pdf version here. This post originally appeared in the journal Lunch Ticket on December 12, 2014: http://lunchticket.org/stand/

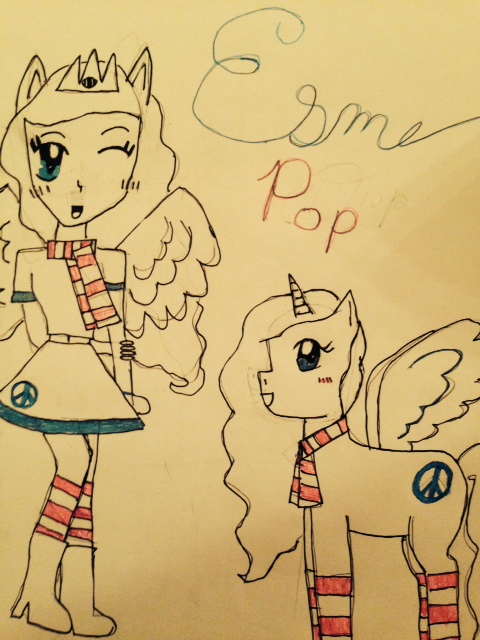

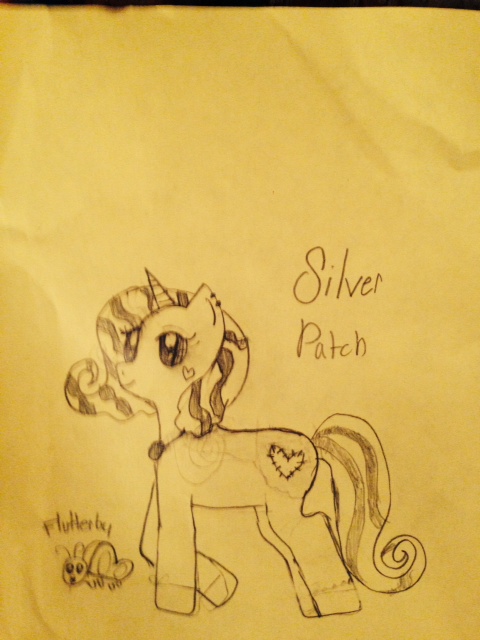

Last night over dinner, after a discussion with our ninth-grader about some challenges she’s grappling with in her personal life, our fifth-grader suddenly asked, “What’s your super power?” I glanced over to her smiling, mischievous face. One of our fifth-grader’s own super powers is the ability to bring levity to difficult moments. She flipped open a sketch book as I thought of our ninth-graders’ worries and wondered if the fifth-grader’s super power will withstand her own impending adolescence. “Here,” she said, clicking her mechanical pencil for more lead. “I’ll tell you the choices.” In shaky cursive she wrote a list. Water, Fire, Magic, Weather, Nature. “Nature means you can talk with animals,” she explained. This is another super power of our fifth-grader. At the barn where she takes riding lessons, she is a veritable Dr. Doolittle. She’s a calming presence among the horses, miniature donkeys, cats, goats, and dogs. There’s even a llama named Ginger who comes when she calls. Our ninth-grader leaned on the table to get a closer look at the list. “I’m fire. Definitely fire.” I exhaled a laugh. Even our ninth-grader chuckled. It’s true, she is fiery. Language has never been a shortcoming for either girl, but our ninth-grader’s eyes easily flash with lightning and her tongue lashes quickly when she senses an attack on her ego or an injustice in her world. Though these girls are not related to me by blood--they are my stepdaughters--I remember being exactly like our ninth-grader in this regard when I was her age. “I’ll tell you the characteristics that go with fire,” the fifth-grader said. In a professorial voice, she cheerfully wrote the words on her sketch pad as she spoke. “Fire: Angry. Destructive. Fighting. EVILLLLL!!!!!” She giggled with mock terror. Our ninth-grader nodded, “Yep. That’s me. Definitely fire.” Her face was neutral, as if this latest trouble had finally doused her fight, and a bit sleepy because it had been a long Monday. “I’m water,” I volunteered. “I can drink enough water to save a city from a flood. I could’ve saved New Orleans from Hurricane Katrina.” I don’t know when I started with the water thing, but it’s been at least since high school that I’ve carried some wherever I go. I only buy purses if they can hold a bottle, and panic a little if there’s no place to refill. “Katrina!” The fifth grader cried with excitement. “That’s her superpower too!” Suddenly I realized what we were talking about. These are the superpowers of the main protagonist and her all-female posse in the book our fifth-grader has been writing and illustrating since third grade. The book was inspired by a game she and her friends used to play at recess. They don’t play it anymore, but recently she informed me that she’s on the second draft of the story. Sitting at the table with the girls, I was suddenly struck by the present moment, and how the three of us held such different awareness of it. The fifth-grader will do almost anything to keep a positive atmosphere. The ninth-grader is invested in protecting her point-of-view. I am mostly interested in doing whatever I can to help these kids navigate their early years so that they grow to be the best version of themselves. As the conversation shifted back to the ninth-grader’s recent challenge, I asked a question here and there, partly to help me understand the events, but mostly to help her clarify them for herself. Right now, of course, it is the end of the world. She struggles because she doesn’t quite know who she is becoming, and has no perspective of the process. At fourteen she’d like all the gates open so she can rush forward, but she has no idea what she’s rushing to. As parents, we try to monitor the gate, regulate the speed, and pull her back in when things are going too far and too fast. The last time I participated in conversations like these, I was the teenager. The beauty of being on the parent side is that time has bestowed perspective. On the cusp of forty I have, at the very least, the wisdom to listen and question, and the experience to consider perspectives other than the limited teenage point-of-view. Lately I’ve been reading essays-in-progress. Some of them are from the Lunch Ticket submission box, others from my colleagues in the MFA program, some from friends who have asked for my feedback. Many of us writers use the page to explore events of our past, and childhood and early adulthood are particularly rich mines. What I’ve noticed as I read through these works-in-progress is that many pieces limit themselves in perspective, despite the wisdom and intelligence of the writer. I imagine that these writers have carried their pain of long-ago events for so many years that they believe the catharsis will come from simply writing their story down. The fact is, we are all the recipient of time’s gift of perspective. Perspective is the power--super power, if you will--of being a writer. As the old saying goes, if you find yourself in a hole, stop digging. While my ninth-grader wallows in her somber thoughts, I, long past those teenage years, can see the hole she’s digging for herself. I can see the holes I dug for myself at that age. As a writer, thinking back to my own childhood events, it is much more healing—and as a reader, light-years more interesting–to go beyond the teenage perspective. As I read these essays-in-progress I sometimes find myself silently begging the author, “What do you, the narrator, think of this now?” Instead of using the pen to only relive childhood events, insert adult insight into those baffling, emotionally-wrought experiences. Let the grown-up wisdom comingle with teenage emotions. As 13th century German theologian Meister Eckhart wrote, “A human being has so many skins inside, covering the depths of the heart… Go into your own ground and learn to know yourself there.” Know what power I wish I had at fourteen? The power to simultaneously hold both the child experience and the adult perspective. Alas, that comes with age. But after living these years, why, when writing our own stories, would any writer eschew this great power? The pen is perhaps the most powerful tool any of us has. How can we communicate or enact change in the world if we cede our own self-understanding? Go ahead, write down those untamed childhood experiences, but lasso them with the perspective of time. When we read your insights, we too transform. Tell me your story of then, from where you stand now. This piece was reprinted at the fabulous online mag RoleRoot on June 2, 2014. http://www.rolereboot.org/family/details/2014-06-cant-attend-middle-schoolers-graduation/ It's a good name - "middle" school. They're not quite who they used to be, and not quite yet who they're becoming. We were so haughty at 6th grade orientation three years ago - we thought we knew our girl. But middle school is somewhere and nowhere at once, and like a tilt-a-whirl it shakes you up and spins you silly till you want to puke. Then it spits you out, wobbling on the street, in an dazed aftershock.

Although I can be sentimental, here at the end of middle school the only sadness I truly have about these past few years is that today my middle schooler moves on, and I won't be at her graduation. In an old-fashioned twist of cold shoulder policy, each graduating child gets exactly and only two tickets for today's ceremony. Only her mom and dad will go. No stepmoms. Her sister, her stepdad, and her godmother won't be there either. Over all, no recognition of the village, or the times, or the tremendous accomplishment that, somehow, all of us survived middle school. Q: How many middle schoolers does it take to screw in a light bulb? A: One -- she holds it in place and lets the world spin around her. Or is it: None -- they're all on Snapchat. The middle school years, with the sky-high and death-valley mood swings, was challenging to us all. The love-is-all and hate-you-all sway; testing rules and parents and pretty much anything from anyone over 30 or without a catchy chorus. These few years have been the toughest of step-parenting so far. Meaning: they have been gloriously rewarding. As a step-parent, I have the dual role of managing my relationship with the kids and managing my relationship with the kids as influenced by their other household. I've tried to keep my eye on the long road -- I have a vision of us ten years from now, sharing a bottle of wine in front of a campfire, shooting the shit, sharing stories. I try not to get caught up in the weather at any particular bend -- even when it has blown in gales from the other household and poured down directly on me. Luckily I have a steady and wise companion. He's known our middle schooler since birth, and he knows the other household well. Like all of us, he's navigated the middle school years without a north star, but when I've gotten close to rocky shore he's shined a light to help me back to calmer seas. There's a sweetness our middle schooler used to have that still peeks out, and I think it will re-emerge more fully as the years go by. The snarkiness that jokingly showed its face 3 years ago became almost malicious through 6th and 7th grade, but lately, mostly, has tapered. She's more self-controlled. More compassionate. More discerning. She's fiercely driven. She gets incredibly frustrated, and is slowly figuring out how to work through her difficulties rather than throw up her hands in feigned apathy. Me too. While she was learning algebra, I learned patience. While she was navigating her social dramas, I navigated dual household dynamics. While her moods were swinging like Madagascar monkeys, I learned to be kinder, more steady, open. She didn't do well on every test. Neither did I. High school, they say, is tougher. But I'm not looking at high school yet. Right now I'm looking at a girl who is almost my height. With blond hair, blue eyes, and slender figure, she's a knock-out, and she looks nothing like me. I wasn't there the day she was born. I missed her first nine years. I didn't help her learn to read, and sadly, never sang songs to her in the bath. But: I measure her height on the kitchen doorpost. I help her with homework, band aids, boys. I am sometimes, when lucky, her sounding board. And when I am unlucky, I feel her fury. She tells me her dreams. She asks me to help her visualize them. She is my oldest daughter. She's big as a grown-up now, but every night we still read bedtime stories. She giggles until tears pour down her cheeks about a line from her favorite book in the Laura Ingalls Wilder Little House series, Farmer Boy. When the lights are turned out, I give her massages to work out the tense muscles from horseback riding and dramas at school. I cover her with a blanket and a hug. I tuck her in. So, I won't be at graduation. I'll hear about it, like so many things, second-hand. I'll see the diploma later, maybe, and the photos of her graceful walk across the stage. But, we'll have a celebration dinner this weekend and begin to settle into the languorous days of summer. We'll discuss plans for the next few months - sleep away camp, time at the barn, Disneyland, camping, bike rides. Of course, if it's anything like last summer, these next few months are bound to hold plenty of drama, especially after camp. It'll be interesting to watch how it plays out. I suspect, though, that it will be a grass-blade's-width easier. She is more polished for the rub of middle school. Ah, don't you know, we all are. Yesterday was the last day of my first residency. While I was at school, Darby and the girls gussied up the house for the holidays. They hung their red and hot pink with gold lame handmade stockings over the fireplace screen. They draped white lights over Ganesha on the mantle. Our old friend, the styrofoam snowman, was planted back in the soil of the potted plant where he sits every winter. The handful of holiday cards we've received so far this season were set up on display. The girls assembled our vintage two-foot-high aluminum tree, hung their ornaments, and plugged in the accompanying color light wheel by the fireplace where the money tree used to be before the roots rotted from my over-zealous watering earlier this year. Hanukah's been over for a while but we tend to pack the holiday decorations all together. Darby made a centerpiece of two plastic dreidels, a cactus, and a frosty-the-snowman cookie tin for the silver thread dining room tablecloth. I walked in the front door at 5 p.m. to a living room bedazzled with glitter and tinsel. It's beginning to look a lot like Christmas.

This must be what Rip Van Winkle felt like when he awakened from his slumber of a hundred years. On the top shelf of our fridge is a sweet potato I baked before school started. I suppose I should compost it, but a part of me still doesn't believe two weeks have passed. I missed Emerson's holiday choir concert, and Esme's acting class presentation. I missed the newest batch of released music, the primary project I oversee at my day job. I've missed emails, New York Times headlines, and Facebook updates. I've missed details never to be recalled about Darby's life. But what would have been missed had I not folded into this MFA program? There’s a lot that’s in theory right now, but I’m pretty sure that once I sit down and actually start writing (I don’t know if this almost stream-of-conscious blog counts) I’ve got a new set of awareness and inspiration to work with. I’ve blogged before about 40-day transformation practices. If I consider these ten days as the beginning of another set of forty, I wonder by mid-January how my writing practice will have changed. It is nearly 9 a.m. and I am sitting here at the table, writing by the light of day streaming through the dining room windows. Faint but distinct synth chords and a melody that Darby has been working on come floating down the hall. The girls are watching Hairspray, both wrapped up in their comforters munching on Honey O's cereal, and I am typing to a little dance number featuring John Travolta in a pink sequin dress. This morning, before the coffee, before the disco music, before I even opened my eyes to the morning light, Darby held me in his arms and whispered over and over, "I got my woman back, I got my woman back, I got my woman back." |

Archives

May 2019

Categories

All

|