|

In my early adulthood, with aspirations not for wealth but for creative fulfillment, I disciplined myself to live down to the bone. I nurtured thrifty tastes, saving my dimes for guitar strings and reeds. With my vegetarian diet, I shopped frugally, buying from the bulk bin, shopping in season and local, for a time splitting a $200 monthly rice and beans budget with a friend. I did not drink much alcohol, did not frequently dine out, did not indulge in fancy coffees or convenient sandwiches, did not buy frivolous clothes. Glad to finally enroll in what I fondly call Hogwarts School of Music, in my first semester at Berklee, instead of scrounging together $75 for a light-weight guitar gig bag, I drilled holes in my heavy hard-shell case and fashioned it with thick piano moving straps into something I could wear on my back. It was heavy, very heavy, particularly with my clarinet and laptop slung over my shoulders. I walked or took the T everywhere, and my back bent under the weight. In a recent newsletter to you, I wrote about raking up backyard leaves in a forgotten spot behind the garage, and my nascent vision of a cabin where I could practice my clarinet, try out song ideas, and work on essays and poems. It's been ages since I've had a room of my own, as Virginia Woolf wrote. I have long wished to sit in a windowed room and stare out the door at pale leaves as they unfurl into spring. I have wished for a room strong enough to withstand a thunder of ideas, because I have lately increasingly felt a rumble rolling through my heart, a heady mix of sound and emotion, art and media, questions and exploration. But I also wrote in that letter about fear of failure. I was worried about wasting money on something so specifically made by me for me. It felt a little arrogant: a playhouse for a grown woman who thinks she's got some talent or ideas worth the expenditure. What if I stepped into that arrogance, that audacity of hope (as Obama says), and nothing, in the end, comes? My fear might be rooted, in part, in an old Jewish superstition of the evil eye: If I do something so bold as build an artist studio just for myself, the heavens may train their unwanted attention on me, bringing tragedy to me or my loved ones. I should spit three times and hang a blue hamsa on the door. My frugality (always for my own desires, contrasted sharply, I hope, with my generosity for others) might also come from the valorization of parsimonious rationing in New England, where I lived for college and music graduate school, but whose culture I had admired since childhood. It suited the environmentalist in me: reduce, reuse, recycle. What throw-away materials might I re-fashion into use? How can I avoid purchasing newly manufactured goods, with their accompanying industrial waste and unneeded expense? But I bent beyond logic under the weight of that guitar case. I hadn't yet read Coleridge's The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, but I rued the albatross around my neck. The irony of it: that in my mid-twenties, finally glad to be at an incredible school and immersed in the study of music, I felt my instrument was a psychological curse I was tasked to bear. It took until my early thirties to examine the cliche of suffering for my art. Till then, I had accepted carte blance the stereotype of the starving artist. Looking back, I realize how easily I could have found $75 for a gig bag, saving my shoulders and neck a little of the physical pain that inevitably comes from the weight and repetitive motion of playing instruments. But I wanted so badly to be an artist, and from the stories I'd internalized, I thought suffering an essential part of a creative life. Fast forward to the past seven years, since Darby and the girls and I moved in together. It's a sweet house. Darby and I often say how glad we are that it isn't bigger. We want to stumble over each other, and engage with the teenagers even when they may prefer to sequester themselves in far off corners. The downside, though, is that I sometimes want to sequester myself away. As a musician, I need to make noise in order to get to the music. I am a lyrical writer, even in my prose, and tend to speak aloud every word as I write (even this, now). I've longed for a dedicated place where I can excavate my artist heart. A room of my own where I can throw ideas around, many ideas, because a good idea is not something that happens in isolation, but rather, comes out with dozens of bad-idea siblings. I've been yearning to throw spaghetti on the walls (I just love that phrase, don't you?) because something must eventually stick. Right? But what if nothing does? In this world of art as commerce, I have feared that the cost of building a little shed for myself won't find a return on the investment. And then I came across a passage in Elizabeth Gilbert's book Big Magic, where she writes, "Let me list for you some of the many ways in which you might be afraid to live a more creative life." This one struck hardest: "You’re afraid that someday you’ll look back on your creative endeavors as having been a giant waste of time, effort, and money." If a friend came to me with an idea, I would urge her to pursue it, to see where it will lead. In fact, after I wrote this post here, I heard from a number of you. Go for it! you said. The compounding encouragement was astounding. Your words amplified a desire deep inside me. So, this is all to tell you: I did it. It's a rule of cabins to have a name: Welcome to Seeds & Thunder, where on a daily basis I meditate, write, play music, and watch the pale leaves unfurl.

2 Comments

To calm my nerves and prep my mind for my performance tonight as part of the Los Angeles Lit Crawl, I invited my office colleagues into the pool room for a noontime 10-minute flash concert. It's actually the mail room, but a few years ago the company painted the walls Persian blue, put in new carpet, and installed a pool table and video game console. I'll deliver a song and a short story, I told them, and added that their presence would be a great service to me, as I haven’t performed in front of an audience in quite some time. It's actually been years since I've stood on stage and performed one of my songs. The invitation came from my hope to ease today's tension of what has been the duality throughout my life. On one side, my desire to sing, tell stories, and connect with an audience. On the other, nothing scares me more.

When: Today at Noon for 10 minutes Where: The Pool Room What: A Quick Practice Run of Tonight’s Song & Story Who: Me and You Why: Because, hey, it’s the entertainment business My earliest memories of singing are a collage: bath-time duos with my guitar-strumming dad; "Tomorrow" at the top of my lungs from the balcony at a Broadway show of Annie and, later, from the balcony of my grandparents' highrise; and, in Hebrew at my Jewish summer camp, "I'm Gonna Wash That Man Right Outta My Hair." Sometime between baths and camp, I learned shame and fear of being shamed. I internalized a philosophy that, at its essence, suggested that anything less than perfection was unworthy. Society? Parents? My own nature? Who is to say where I learned it. Stage fright is a bully. But I have songs and stories in my heart, and I am certain that if I don't answer their call, the incessant knocking will drive me mad. The anxiety was never as bad in orchestra and small chamber groups. I played classical and renaissance music from a young age through my mid-twenties, and frequently sat as first-chair in the college and community groups. In orchestra and wind ensembles, inevitably a solo line popped up here or there. I'd fret over those measures for minutes before they came, but I loved the sound of my singular clarinet soaring over the other winds and strings. Sitting in my formal black and white attire, I could be heard and not seen. When the momentary solo faded back into the wash of music, my nervousness calmed. I was just a vessel for the music amid the other players and a clutter of music stands. In my last year of college, I won a prestigious competition hosted annually by my university's music department. As the winner, I would be the featured soloist at the spring orchestra concert in an orchestral piece of my choosing: the Weber Concertino for Clarinet. Even more than the honor of winning, as soloist I had, for the first time, the opportunity to perform alongside an orchestra. Whereas in the past I'd only had piano accompaniment, for this I rehearsed alone and, later, in the concert hall with the full orchestra. In the throes of stage fright, I can never think clearly. I rehearse to perfection beforehand, in the hopes that in the moment I will be able to deliver a large fraction of that excellence. But rehearsal is not fear-proof. On the day of a performance, my stomach churns for hours, my legs feel numb. On stage, I sweat, I shake, I forget how to do the very thing I have practiced to flawlessness. But I fake it in the hopes that one day I will make it without fright. Unsurprisingly, as the days led up to the concerto performance, I was a wreck of jitters. I knew the concerto competition concert would be the most well-attended of the year. My parents and grandparents, none of whom later attended my college graduation, all flew in. A few days before the concert, I confessed my nervousness to my mentor, Sarah Mead, a beautiful viola da gamba player who had introduced me to Early Music my first semester and nurtured me through all four years like no one ever had. Sarah and I had both skipped grades in elementary school, and bonded over the lifelong sense that we'd missed some essential lesson only taught that particular year. She introduced me to the beautiful music books of the renaissance, with their four lines of music facing the four outer edges so that a family could sit around a table after dinner and play music together. Sarah knew I loved a challenge, and whenever our Early Music ensemble called for a new instrument, she gave me the task of learning: recorders, harp, krumhorns, flutes. Later, after I graduated, I couldn't bear to leave Sarah, so I continued to commute to campus for weekly rehearsals, until I finally moved away. The week of the concerto performance, Sarah told me about the first time her son Patrick played piano for an audience. He was around seven, and he was to play a solo piece as part of the university's celebration of composer and music department founder, Irving Fine. Sarah had worried about his nerves, but when she woke Patrick on the morning of the celebration, he sat up in bed with wide eyes and big grin. "Mommy," he said, "today's the day I get to play my song for everyone." That Sunday, while the orchestra played through the first half of the program, I sat in the green room smoothing my dress and repeating Patrick's words. "Today's the day I get to play my song for everyone." I thought over and over, my fingers shaking on my clarinet keys as I ran through arpeggios, my empty stomach clenching. "Today's the day I get to play my song." I heard the applause and walked onto stage. "Today's the day." I nodded to the conductor and he lifted his arms for the string opening. I am tempted to write more, to tell you how I wet the reed, how my first note rang in the hall, how playful the theme and variations felt tripping off my fingers, how the orchestra buoyed me, how the cadenza I'd written for the near-end felt like a braiding of my own music with Weber's. I am tempted, but I can't, because I don't remember any of it. I only remember feeling a profound sense of shame at the end. Nothing terrible had happened -- I didn't forget a line, my clarinet didn't squeak -- but I remember afterwards wanting to hide from the family and friends waiting in the hallway with bouquets in their arms. For years after that concert, I hid my accomplishment -- the competition, the performance -- convinced that I'd not deserved the recognition. Perhaps that year the competition had been slim. Perhaps I, a far cry from the winners of years past and future, was only the best they had that year. It should have been a glorious moment, a capstone to years of practice and study. But all I could think was that I'd had one chance for perfection, and I had not achieved it. Not long after, I packed away my clarinet. Meanwhile, sometime in college I started writing and singing songs. I wanted so badly for someone to listen, so after college I met my fright head on. I wanted to capture Patrick's joy at sharing something that he loved with others. Following the footsteps of my juggler boyfriend, I bought a busking permit at the Cambridge city hall and every weekend plugged my two-input amp into a car battery, laid out my guitar case for tips, and played for passersby in Harvard Square. When the air turned cold in early October, I donned a winter coat and fingerless gloves. When the Head of the Charles tourists left town, I turned to open mics at Club Passim, the Kendall Cafe, and other songwriter venues that have since closed. Over the years, I pulled together a band, I recorded, I toured. Stage fright still gnawed, but I fought it with a combination of coca cola and gin, and the frequency of performing forced my anxiety into a tenuous remission. And then, ten years ago, I stopped performing almost entirely, and stage fright became a thing I know about myself but didn't have to face on a daily basis. The songs no longer wanted singing, so I no longer needed a stage. My guitar joined my clarinet, and though I occasionally I strummed some chords, for the past ten years I've not felt any great urge to perform. Until now. I woke this morning with wide eyes and a smile. I cannot explain this excitement: I haven't felt it in years. My hands are shaking, and my stomach is churning, my legs are numb, and I'm afraid that despite my practice, I won't be perfect. But beyond all fear, tonight is the night I get to play my song, tonight is the night I get to read my story. Me in the pool room: This piece originally appeared in the online journal Lunch Ticket on September 12, 2014: http://lunchticket.org/courage-it-takes/ Sitting under a café umbrella recently, sipping iced tea with an MFA colleague, the conversation naturally, unsurprisingly, turned to writing. We’re both in our second semester of graduate school. As I’ve mentioned previously in this blog, I’m “Creative Nonfiction.” It’s a fact which never ceases to amuse my fiancé who takes it as an existential statement. My tea-sipping friend is “Fiction,” which amuses my fiancé even more.

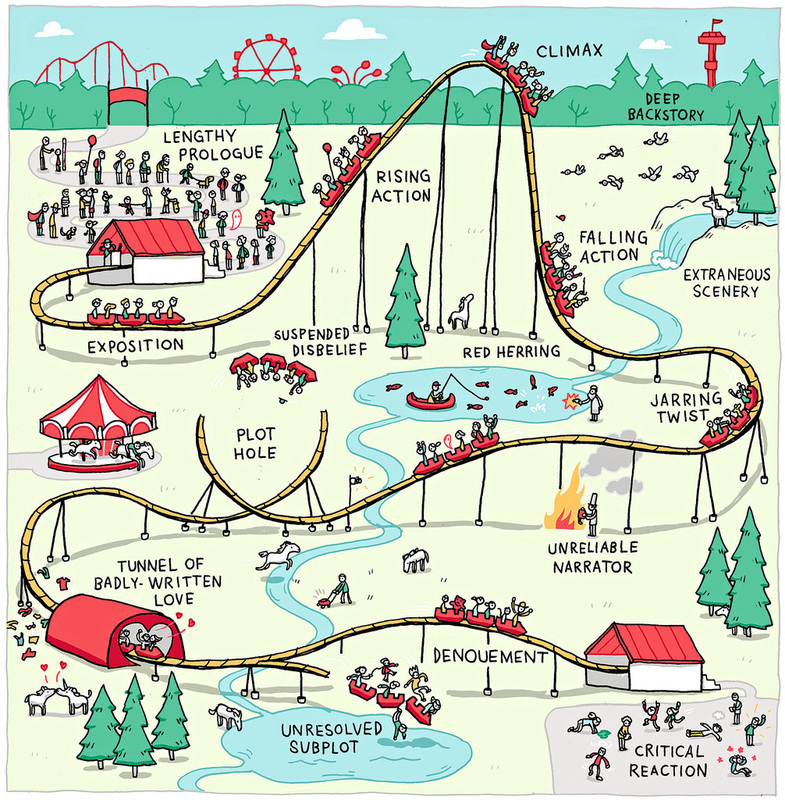

Regardless of fictive or nonfictive embodiment, my friend and I both agree that the monthly packets we are required to submit to our MFA mentors are very real. Troublingly so. My most recent packet of twenty creative writing pages and two book annotations was due to my mentor in mid-August. For two days afterwards I celebrated its completion by not writing a single word (status updates and margin notes inBehind the Beautiful Forevers, of course, aside). On the third day I intended to get back to writing, but—nearly a week earlier than expected—I received my mentor’s return email: a detailed letter, in-line track change comments, and lecture notes on a particular topic she suggested I study. I was paralyzed for a full week afterward. Could. Not. Write. Anything. I sat with my friend at the outdoor café during that time. It was one of those blazing hot Saturday afternoons when everything melts: ice in our drinks, lipstick in my purse, ego. We sat together, pulling our sweat-soaked shirts away from our backs, fanning cigarette smoke from the table next to ours. Inside the café, the A.C. was on full blast but the room was crowded with chatter, and she and I both had some things to get off our chests. She, too, had a hard time getting back to work after sending off her last packet. “I’m afraid of criticism,” she said. It was powerful to hear her express what I had been feeling. Of course criticism—particularly at the hands of a knowledgeable and supportive mentor—is meant to be helpful. Indeed, it’s a primary element of why we both came to this program: to receive critical feedback about our work. But the fear we associate with criticism is attached, I think, to shame. Shame that the basket we’ve put our eggs in is full of holes. Shame that we will fail. Shame that there is a right and wrong to writing and that, ultimately, it is just beyond our personal abilities to get it right. Fear that we are not capable of stepping into our highest creative self. My friend’s reflection of my own fears was enough to remind me of a time, years ago, when I had not allowed my fears to stop me. After years of studying classical music, sometime in college I ended up with an acoustic guitar and a book of folk songs. Joni Mitchell, Pete Seeger, etc. I had been raised on these songs by a guitar-strumming dad. My first concerts were folk festivals where my parents spread a blanket and we picnicked on my mom’s cold fried chicken and berry pies. The folk songs in the book hit a deeply personal spot from my earliest childhood memories. It was a place that classical music, as much as I loved it, had never tapped. The book was a doorway, and when I walked through it, I walked away from classical music, stepped onto a path of songs, and, shortly, started writing my own. Right away came the desire to sing for others. A moment later, my stomach clenched with fright. Stage fright, like fear of criticism, can be debilitating. It can also be exhilarating. I’m not a fan of roller coasters, but I wonder if the draw to them is similar. Do coaster-lovers shake in fear? Do they wonder if they can handle it? Do they get a rush from the courage it takes to ride? This is what it feels like, for me, when I send in my mentor packets. I silently beg, as I hit send, that my mentor’s feedback will be enough to kindly push my edge, an edge just shy of disablement. Often, to work out fears that arise in my new(ish) writing endeavors, I look back to my life in music. How did I overcome my life-long stage fright so that I could pursue my love of singing and songwriting? I showed up. Back then, I was up against all these same fears of failure and shame, but my desire to get better at my craft was larger than my fears. I knew the only way to improve was to do it. Perform. As much as possible. The solution? I joined the busking world. I didn’t have to wait for a club booker to let me in the door. I could pull up a piece of sidewalk and play every night, which I did throughout summer and fall until my fingers froze, and then again the following spring. There was a good community in my Boston busking world days—Amanda Palmer, Guster, Mary Lou Lord, and many others who passed through for a week or for years—but also, I learned to stand up in front of an audience. I learned to show up against my fears. After a few hours at the café, our iced teas were finished, our conversation spent, our backs sweaty. I drove my friend several blocks to where she had parked. “I made something for you,” she said as she unlocked her car. From the backseat she pulled out a pale green cotton bag with two wide shoulder straps and a red and white swath of cloth down the center. I can’t sew at all, but I appreciate the craft. Her stitches were perfect. The muted colors were imbued with my friend’s gentle spirit. The kindness was almost overwhelming. Fingering the stitches of my friend’s gift, I remembered something an old teacher used to say: How you do one thing is how you do everything. I haven’t read my friend’s writing, not yet. Nor has she yet read mine. But I am certain that when the day comes for us to exchange not just our trepidations but our art, we will find in each other’s writing the level of courage, commitment, and care that we bring to our other arts and crafts. As with everything, sometimes fear stops us for a few days or a week. But always, every time, our desire to do this—to explore questions, share stories, to write—leads us through the turnstile and back onto the ride. Today I am full of doubt.

Now, in the black and white font of this site you might take pity on me, or feel bored with this typical and on-going issue, or not care either way. The latter I cannot help, but regarding the pity, don't give my mind-chatter any moment of compassion. I'd rather it not be fueled by any attention whatsoever. The moment you engage, it's off to the races. I've heard mind-chatter described like a television channel or radio station, but I don't agree. Those boxes can be changed or turned off at will. You can turn down the volume. Walk out of the room. Mind-chatter is more like an eight-year old kid. Do you happen to have one around? If not, I'll tell you - they are on constant chatter. They bounce from topic to topic. They talk like drunks. The moment you open a book to read, they lay on top of it. They climb on the back of the couch, let Cheerios lay where they fall, and leave the box of crayons spilled across the couch even though they've moved on to choreographing a dance. They ask questions, and then shift gears the moment you try to answer. They are hungry, starving, and hate the casserole you've made. And did they tell you about the game they played at school? Yes? Okay, let them tell you again. There is no inner dialog for an eight-year-old that does not, without filter, become the outer dialog. Like the eight-year-old, the mind will chatter. Like the heart will beat, the lungs will breathe, the inner psyche will run on and on with an endless stream of story-line. The main difference between the heart and the mind is that while the heart beats regardless of the attention you bestow upon its actions, the mind wants attention and will try any and every way to gain it. "I am beautiful" is, apparently, not interesting dialog. There's no inner turmoil in that, no engagement, no drama. It turns out that simple love stories won't do. A thought like "I am beautiful" is tossed out as soon as it arises. But give me soap operas and I'll be hooked all afternoon. When I sit down to write, as I have done today, all I think is "I am boring", "I cannot do this thing", and "why bother trying - someone else can do it better". In light of my recent readings of Herman Melville and Virginia Woolf, it is so easy to go there. Their books are extraordinary, and so that's where my mind-chatter goes. Like the eight-year-old, the mind wants attention. It will use every trick in the book to get it. I texted Darby a few minutes ago: Me: "afraid to write. afraid of being boring or having poor judgment or telling a pointless story." him: "i totally understand. what you write might be all of those things... or not. you just gotta write. it's not your last piece. nothing rides on it. some hits some misses. and brooke just brought over some yummy donut creation. if you write, you can have some..." I'm not above coercion, or anything doughnut related, but what I would give for useful mind-chatter. How about something helpful like "ah, this is how we will develop the structure". I mean, shouldn't my mind and I be on the same team? A good-natured chat like, "hey, Arielle, there's a cool simile - come on, try it out" would be very welcome. So I've been thinking - practice makes perfect, right? Well, it seems I've perfected saying to myself things I would never think to say to someone else. Sure, I make mind-quieting meditation a regular practice in my life. That has helped me calm down, be present, let go. But today I'm starting a new practice. This one is not a practice of quieting the mind - it's a practice of writing my own script. I'm going to start small - just as I did with the mind-quieting meditation six years ago. Two minutes. Two minutes by the clock of meditating on a new mantra, in plain, simple English. I am talented. I am extraordinary. I have a talent for storytelling. I have a way with words that the world wants to hear - through stories, through songs, through teaching. I need more stories like these chattering away in my mind, so I am going to start practicing them today. After all, I am a writer, aren't I? I write a lot about doubts because I have so many. I spent the first half of my life -- actually, perhaps the first two-thirds -- accidentally incorporating other peoples' fear-based beliefs into my own psyche. Metaphorically, in a right-handed world I was a lefty who was taught, and later bought, the story that right-handedness was the way I should be. An artist must struggle, according to the lore I was handed, and can either starve or give up the art. I tried both of those options for years before I became suspect about the credibility of my source.

These options -- to either starve or give up -- are not the only possibilities. That emperor has no clothes. There is actually nothing to support that narrative except the perpetuation of that story. When I moved to Los Angeles seven years ago, the city itself cracked open the false front of that narrative. It is a fear-based and limited story, and Los Angeles reveals the ridiculousness of it every day. This city is built on and by creative artists of all types. L.A. is a testament to the power of vision. You can talk about the smog or the traffic jams or the sky high real estate prices, but if you really want to talk about the essence of L.A., you've got to talk about dreams, and that dreams come true. In sixth grade I participated in my class's lip sync contest, bouncing around the gym in colorful '80s leg warmers, mouthing the words to the Starship hit song that year: We built this city on rock and roll. I've rarely thought about that song since. Were they singing about Los Angeles? The other day in the Breath and Writing workshop, we focused on the physical act of breathing, and also the way that breath comes across in writing. Then, after two minutes of matched inhales and exhales, we put pen to page and were asked to write about the thing that resides in the deep, hidden folds of our breath. I found myself bored with fear and doubt. I've written enough about those things. Instead, I flipped the coin over and explored a new story. My pen tested out another line of thought, one about possibility, limitless and authentic expression, accepted and applauded vision. There's a story I sometimes talk about in my yoga classes about a man walking down the street and falling into a pothole. Perhaps you've heard it before. A man walks down the street, and everyday stumbles into the same pothole. One day the man walks down the street, and while he stumbles into the pothole, he sees it first. This is his awakening. He still falls, but he is aware for the first time that the pothole is his pattern. Later, the man walks down the street, and sees the pothole before he stumbles. That day he instead has the consciousness to walk around the pothole. In the final piece of the story, he eventually takes a different road entirely. I am not yet on a different road. I've been writing about the pothole, still often stumbling in, sometimes able to walk around it. Sometimes I end up circling it for days on end, peering into its depths. In the Breath workshop this week I took a test stroll down another street. It was sloppy and I felt the pull back to my old familiar territory. Doubt and faith are bedfellows that cannot occupy the same space. I've been sleeping with doubt for too long, but faith is still a new companion. Seven years in Los Angeles, and every year I find a little more faith. Who would have thought that this city of heathens would teach me this, but it is, and as time unfolds I learn more. Here is a David Whyte poem that I always remember, nearly every day when I am gripped with self-doubt. I am thinking of it again today. FAITH I want to write about faith, about the way the moon rises over cold snow, night after night, faithful even as it fades from fullness, slowly becoming that last curving and impossible sliver of light before the final darkness. But I have no faith myself I refuse it even the smallest entry. Let this then, my small poem, like a new moon, slender and barely open, be the first prayer that opens me to faith. -- David Whyte Naturally, after years of northeast city living, I walk fast. Last night, soaked from head to foot after a spin class, I slowed my pace. My car (utilitarian, dirty) was in a lot (street level, gated, manned), same place I parked for Monday's class. I noticed the unusually warm November air, and the pitch black sky (no stars, no moon), and the lights ablaze on the backside of a three-story concrete apartment building at the far side of the lot. It's common knowledge that to be a writer one needs to slow down and notice things.

My new book bag arrived in the mail yesterday. Last night after spin, not exactly at their request, I gave Darby and the girls individualized tours of the (let's count together) sixteen (or did we miss one?) pockets. There are pockets within pockets and it gets very confusing, but the most important thing is that there's space for my (printed out, three-hole-punched, three-ring-bindered) reading materials and (new) laptop. In addition to the bag and the laptop, a few weeks ago I went to the eye doctor for the first time in six years and am now wearing new glasses (Prada like the devil). Also, I have more student loan debt. Apparently I am going back to school. Do I look smarter? Am I more organized? Will my new bag and laptop and everything make me focused, disciplined, witty, and desirable in smart, creative, insightful ways? Dammit, will these new specs and my sixteen (or seventeen) pocket book bag help me achieve all my professional, creative, and life desires, which include a charming, perfectly-sized house in a small town with agreeable weather (some rain, plenty of sun, cool enough for layers, warm enough for bare feet), beloved students and colleagues, published books and essays, and plenty of time with Darby to explore exotic and familiar places where we can be both adventurous and lazy? Ah, welcome, mind-chatter. Of course. Have a seat, set up shop. Like my new book bag, there are pockets within pockets, and there's always room for more worried inner-dialog. One thing my mind chatter does not refute is that I am an attentive listener. One of my past writing teachers always insisted on grounding details right from the start. Let the reader know who, what, where, when, and how, she would urge, but look at me here. Even with the MFA acceptance letter, new glasses, and book bag, I cannot hide from the fact that I will fail. I have already forgotten the grounding details. Who: Yours truly, the timid and fierce dreamer in residence. What: MFA in Creative Writing with a focus on Creative Non-Fiction (but explorations and possible semester in Fiction). Low Residency program. Where: Antioch University Los Angeles. When: Beginning in a few weeks on Thursday December 5 at 6:00 p.m. How: With a good amount of anguish, I suppose. The low residency format of this MFA means I will be on campus for ten days each semester, for four or five semesters. Ten days on campus attending workshops and seminars, followed by five months of 'project period' in which I will write and submit, among other things, twenty pages monthly to my mentor. In preparation for one of the upcoming December residency seminars, I re-read a passage in Anne Lamott's book Bird By Bird. In her chapter titled The Moral Point of View she writes,"The core, ethical concepts in which you most passionately believe... telling these truths is your job." Sorry about the profanity, but Dammit, Jim. What are the core, ethical concepts in which I most passionately believe? Lamott is not asking for a superficial answer about what I like, or to what I am agreeable, but that which I most passionately believe. She writes later, "Reality is unforgivingly complex." Hell right it is. Is there a closet to hide in, because this stuff is pretty intense. How do you unravel your passions enough to get at Truth, with a capital T? Can I not just live in keeping with my values, hopefully bring that to my yoga students and my kidlets? Doesn't she know that the Prada glasses are just a ruse? Apparently not. Lamott is saying Arielle, dear timid and fierce dreamer in residence, you can quietly live whatever life you want, but if you are going to write about it, you need to step up to the plate. And, by the way, you're the one who put the application in the mail to Antioch, with an excerpt from the book you are writing about the time you toured the country for five months with your band. You went to one of the top music schools in the country despite unholy cries from your nuclear family about how you cannot and should not pursue the life of an artist. YOU HAVE DISMANTLED YOUR LIFE EVERY TIME YOU FOUND IT WAS INAUTHENTIC AND REBUILT THE FOUNDATION FROM SCRATCH. Yeah, Ms. Lamott. I guess stepping up to plate is kinda my modus operandi anyway. I just wish I could do it with a little less commentary from the inner critic peanut gallery. In the shower this morning, I held the bar of lavender soap and closed my eyes, trying to find the words to describe the sensation in my hands. No words came, so I simply washed my face. I pressed my fingers against my closed eyelids till sparks of color and geometric lines lit up against the darkness. How would I describe this? I thought, and wondered if it looks the same to everyone. Again, no words. It's one thing to slow down and notice. It's entirely another thing to have the skills of phrase. Language art. And then, beyond that, to actually say something of substance. Express that which I most passionately believe. Perhaps this MFA is just an expensive way to confirm that you are not gifted in this realm, says my inner voice. Given this lifetime of dialog between us, I'm thinking I should consider giving my inner voice a name. Like Syd or Pup or Marcia. Yes, Syd, perhaps this MFA is just an expensive foray into failure. Meanwhile, Syd, it's still morning. I've got my coffee to drink, and if you don't mind sitting over there quietly for a while, I will journal for a page or two to clear my mind, and then I intend to sit here at my new laptop for a bit. After all, if you're done talking, I'm in for another day of writing. I was taken off my yoga mat the other day mid-class to find my phone and jot down a note. My mat was rolled out in the front row at the far end of the studio room, the furthest I could be from the cubbies where we students stash our belongings. As everyone else lifted up into a warrior pose, I crossed in front of twenty or thirty mats to dig out my iPhone. I couldn't have been more distracting. One of the practices of yoga is clearing thoughts from the mind, but I didn't want to risk losing this one.

That was Sunday, and now it's the middle of the week. In these between days I've felt a tightening, like a bag I keep cinching closed. I've distracted myself with snacks and articles and jewelry designer websites, but like a kitten scratching at the bedroom door for breakfast, as much as I try to go back to sleep, the idea still lingers. There are other ideas too -- integration, which is something I've been thinking a lot about, and Lovember, which is an idea/project/mindfulness practice that I am embarking on this month -- and I'd rather write about them. Alas, Sunday's yoga interruption is the one caught in the bottle neck. Nothing else can come out until this one does. Here, then, is my attempt at loosening this bag, at softening around the idea I've tried to tie shut, at releasing some of the lurking darkness. There was a viral youtube video that went around a few years ago. It first emerged in 2007. Perhaps you saw it? It was an experiment arranged by the Washington Post for one of the world's most talented violinists, Joshua Bell, to perform incognito during rush hour in a Washington D.C. train station. For one day, the virtuoso was virtually unknown. Spoiler alert: he was mostly ignored. For here I'm a tad more interested in what happened on Sunday (but you should really read this excellent Washington Post piece about what happened that day in the train station). My sweetheart Darby teaches the yoga class. He's a well-loved teacher, and it's a popular class. Throughout a regular Sunday there is laughter, some groaning, a few f*bombs, a lot of sweat, and occasional cathartic weeping. A sense of camaraderie has developed among the students. We are all human, we are all perfectly imperfect, the class seems to say in a collective sigh. Sundays are less about silent meditation and more joyful celebration. On this particular day, as we moved through prasarita padottanasana (wide legged forward fold) and some standing twists, Darby talked about awareness. He mentioned the recent Banksy stunt in NYC in which the elusive graffiti artist set up a stall near Central Park and sold (via an unknown gentleman) authentic Banksy prints for $60 - and had only three buyers. Oh, whoops. Spoiler alert. Darby was pretty much asking us to wonder, how often do we rush by things of beauty, interest, poignancy? How much do we miss? He also mentioned the Joshua Bell experiment. As various articles about this ask, "If we do not have a moment to stop and listen to one of the best musicians in the world playing the best music ever written, how many other things are we missing?" Well, that's a good discussion, if you're considering the viewpoint of the passersby. In fact, more often than not, we are the passersby. But what about when you're the busker? In fact, this conversation on Sunday hit home because I was the busker. In the mid/late '90s I stood with my guitar on the gusty train platforms and sidewalks of Harvard Square, offering my art to anyone who had the time. Much like the Joshua Bell event, my busking was also an experiment. I loved writing music. I loved singing. What I didn't like was the gut-wrenching, finger-numbing, throat-tightening anxiety that gripped me every time I stepped on to a stage. I wanted to love performing, and the best way to do it, I thought, was to perform as much as possible. I bought an amp with two inputs for voice and guitar, a boat battery to power the amp, and a bright red dolly to lug it all out to the street in a compact package on wheels. The good times were when it wasn't too cold, and someone sat down on the sidewalk to listen, say a kind word, or put money in my guitar case. More than fifteen years later I still recall the night a man handed me one hundred dollars - five twenties, actually - and told me to record my songs, and the afternoon one of my local idols, folksinger Catie Curtis, stopped to listen for a few songs. There were times of encouragement, but mostly it was a practice of ignoring being ignored. Joshua Bell and I have at least this in common. When I look back on those busking days, I remember a few people resting nearby to listen, but I mostly remember the passersby. Until this week, I had almost forgotten that getting over stage fright had been my main reason for the busking. As it turns out, my experiment mostly worked. The anxiety never entirely went away, but it certainly lessened. Yoga helped with the rest. But until this writing, when I've thought back on those busking years, I've mostly remembered them through the lens of failure. It would take a heart of steel to overlook the hundreds of people who never knowledge the music. That's what gripped me the other day in yoga. In addition to Banksy and Bell, Darby mentioned another incident of an overlooked artist: the band U2. Years and years ago, before U2 was known by anybody here, a friend of Darby's shot a few photos of them. They were performing live at a club in Dallas as the act between wet t-shirt contests. Unlike Banksy and Bell, they were not famous at that time. Maybe they were ignored because they were unknown, or because the club patrons were only there for the other shows. Possibly they were ignored because they weren't any good. The point, I realized, is that it doesn't really matter. What matters is that they didn't stop there. The band didn't let past failures be the measure of their future success. This is what I had walk across the yoga studio to write down: Do not base the possibility of future success on the memory of past failures. Too often I look at my past in an attempt to predict my future. After all, we are the only case study any of us really have. More often than not, I consider something a failure if it didn't meet the high expectations (and generally short time frames) I set myself. I've looked back instead of forward. I put lack of success on a pedestal and declared it The End instead of resting it on the side of the road and continuing the journey. Too many times, I've rubbernecked disasters instead of keeping my eye on the road. So here we are. November 1. This is going to be an interesting month. For a long time now I've been looking forward and setting measurable goals. I did get into the MFA program. I did finish the marathon under five hours. I did book the gigs. This month of November I've renamed Lovember. I'm dedicating it to a different sort of growth, one with no measures. There's going to be a lot less rushing around, because Lovember is not about check lists. Lovember is about kindness. Joy. It is about showering the man I love with love, and writing because I love to write. This Lovember I am keeping my eye on the things I hold at the center of my heart's bullseye, and not letting past failures be anything other than one lens through which to look at history. |

Archives

May 2019

Categories

All

|