0 Comments

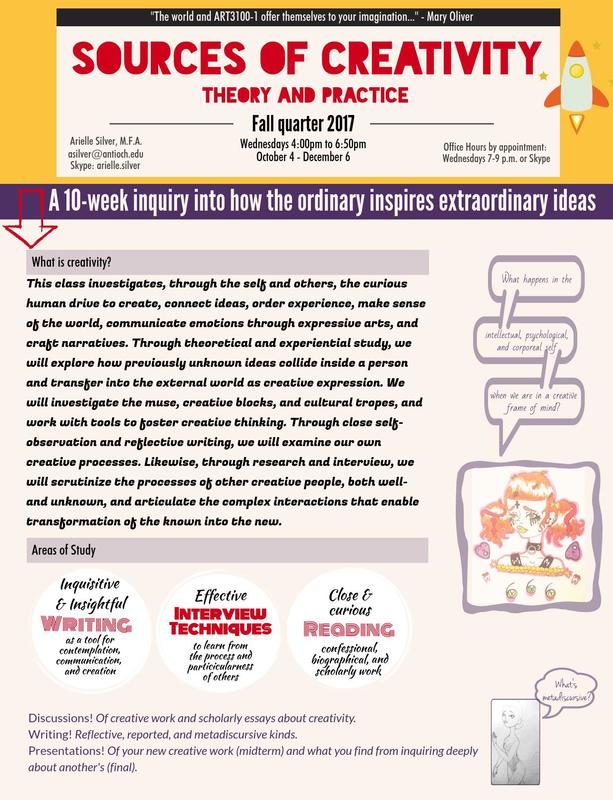

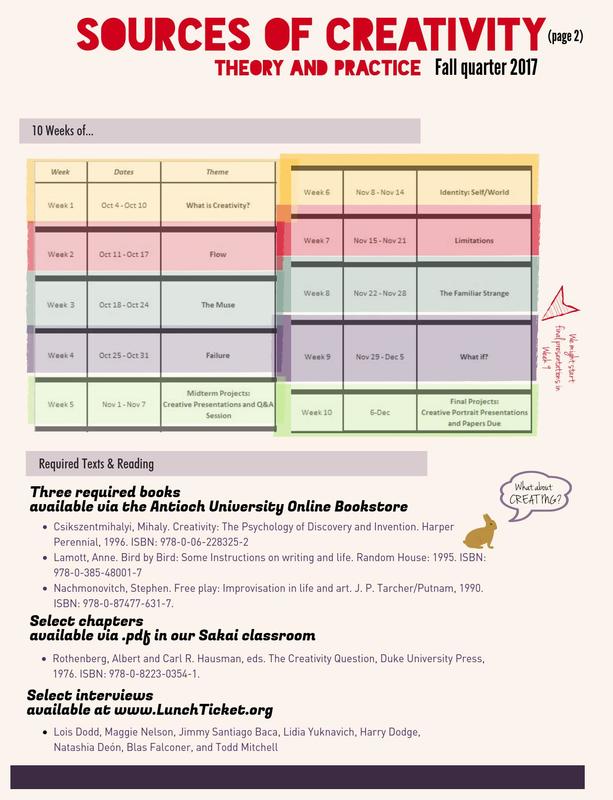

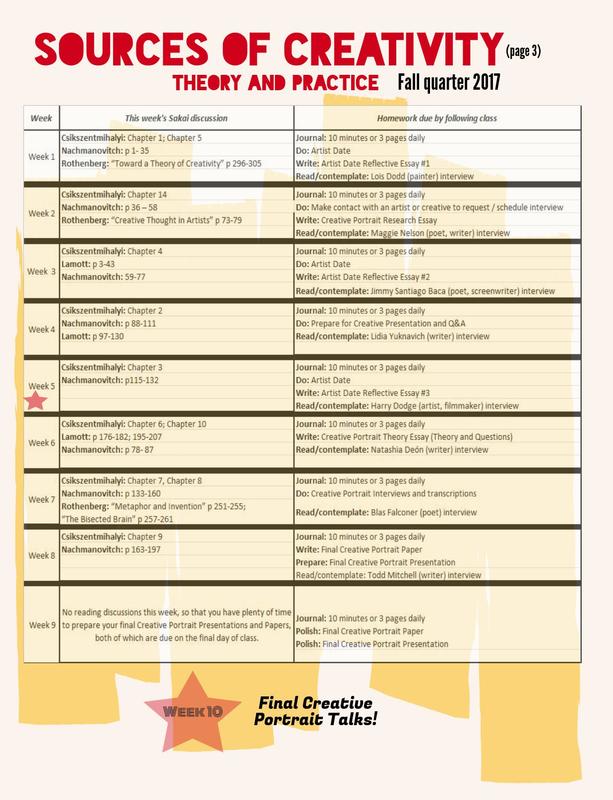

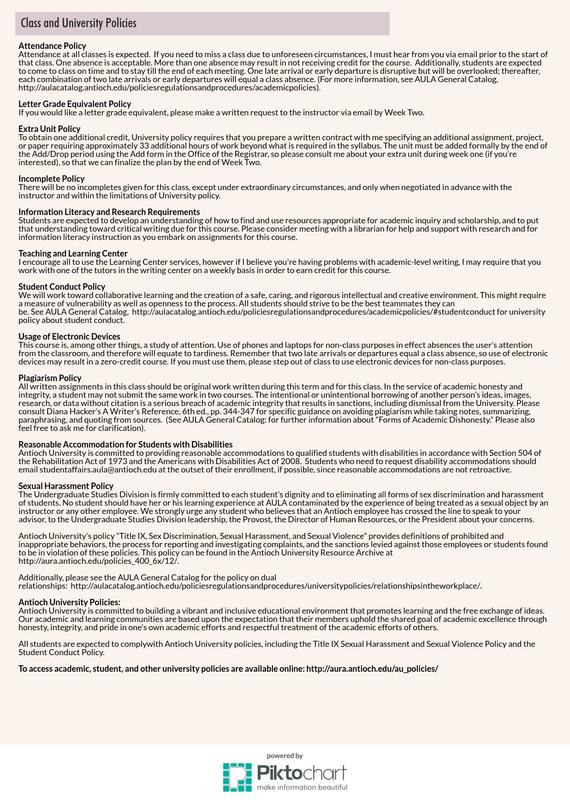

Last night was the first meeting of "Sources of Creativity: Theory and Practice," a course that I'm teaching this quarter in the BA program at Antioch University Los Angeles. The students come from a wide variety of backgrounds and with a broad array of creative experience, from poetry to visual art to acting, photography, coding, skateboarding, and scriptwriting. About midway through the three-hour class, as we reviewed the syllabus, a colorfully designed nine-pages with its outline of the quarter's assignments and midterm and final projects, dotted with drawings from my 13-year-old artist-stepdaughter, I sensed an unspoken concern in the room. How, I almost felt the students' thoughts, would this instructor evaluate our papers and projects - our creative work and our personal reflections on our process.

Ah, yes. This is where we need to start, every time, but especially in a setting like this one: a college classroom strewn with desks and chairs and whiteboards, all bright and muggy under the florescent lights. Especially when the students are all-too cognizant of the evaluations they will receive from me, their evaluator, at the end of the quarter. I looked up from the schedule of academic rigor, scholarly essays, and details of how I will assess their work, to get back to the essence of what it is I hope will happen in this class over the next ten weeks: I hope they will create. I hope they will dig through whatever resists that desire, and come out the other side. I hope that by doing this together as a class, interviewing artists in their world, reading scholarly theories by Csikszentmihalyi, anecdotes from Anne Lamott, and spiritual inquiry by Nachmanovitch, they will find themselves among creative spirit comrades, and feel inspired. Art is a process. Creative thinking is a process. Self-inquiry is a process. Exploration of the outside world is a process. Looking at the ordinary from a different angle... process process process. So is the development of a class syllabus. I'll write more on the process by which this one came to be, but for now I'll leave it at this: When the students saw this syllabus, colorful and chunked and so unlike the common-looking black and white 12-pt Times New Roman font Word doc, they smiled. SMILED at a syllabus. I keep smiling at it, too. If, like me, you're rather east-coast oriented, you would be surprised at how many north-south hours you can drive in California without crossing the state line. Even outside of Los Angeles rush hour, the southland continues for quite a while through beach towns, industry, and military land till you hit San Diego and, quickly after, the Mexican border. Meanwhile, your twin in Eastern time could tour all the New England states and maybe even hike Mt. Monadnock round-trip while you push 85 from San Francisco to Oregon, ignoring the celebrated and twisty path of Coastal Highway 1 that wends through eucalyptus and redwood forests and ocean views. Years ago, when my band got to California on the west coast leg of our national tour, we took the fast farmland-country Interstate 5 from LA to SF and beyond. Kerouac not withstanding, when you're traveling with others in a van for months on end, sometimes you just want to get there, and we always had a solid schedule to keep. Pacific Coast Highway 1, though, is the pretty one. You don't take it when you're in a hurry to get somewhere; you take it to gape wide-eyed at the beauty and imagine a different life. Darby and I have driven the PCH from Los Angeles north to Big Sur on the central coast many times, stopping for a complimentary (Darby composed music for their films) tour of the magnificent Hearst Castle, goggling the blubbery elephant seals piled up and jousting on the sand, and, finally, twisting through Big Sur's craggy beauty on our way to our favoriteglamping spot, TreeBones, perched high above the surf. This year, Big Sur is inaccessible from the south due to last winter's giant landslide over Highway 1. Sadly, it may be a few years before we again pitch our tent at TreeBones, browse the shelves at the Henry Miller Library, soak in Esalen's hot tubs, stuff ourselves on too much Big Sur Bakery bread, hike to the Tin House, and hunt through shells for jade. However, last week Darby and I had good reason for our first road trip far north of Big Sur: our friends' wedding in Davis put us already five hours north of LA. We decided to extend our trip and experience a new slice of the Golden State: Mendocino and Marin counties. With Al Franken's new book, Giant of the Senate, on audio, after the wedding we swung north up I-5 and then northwest on Route 20, motoring alongside Clear Lake (at 68 square miles, the largest freshwater lake wholly in the state) and through Jackson State Forest until we hit the coast. Then we scooted up a little along the northern slip of Coast Highway 1, and spent five days hiking, beachcombing, and eating a lot of cheese, as we made our way back south. We stayed at two Airbnbs along the way -- the first in Elk, just south of Mendocino, and the second in Bolinas, a quirky little town in Marin County with one bar, two restaurants, and no road signs pointing the way for travelers. Though we knew that the residents of the unincorporated community notoriously take down Bolinas road signs until the county finally stopped putting them up, we still fell for it and overshot the town by about 20 minutes. Our friends' wedding coincided with our own second wedding anniversary, but life has been busy lately, so most of our plans were made last minute, finger-on-the-map style, asking each other only a week earlier, "Where can we stay?" and "Want to go here, doll?" However, there was one place we knew months ago that we would visit: Glass Beach in Fort Bragg. Nearly eight years ago, when Darby and I were still fairly new to each other, we drove "over the hill" for an afternoon stroll along a quiet beach near the intersection of our local stretch of the Pacific Coast Highway and the coastal tail of Topanga, one of the famous Los Angeles winding canyon roads. We slurped hot lemongrass soup at the Thai restaurant across the street, and then noticed the golden light of the nearly setting sun. After our soup, we froggered across four lanes of the PCH to the beach on the other side. It was probably a Sunday: Sunday was our day. A heart-shaped aluminum balloon floated above one of the restaurant tables, which I remember seeing and realizing that Valentine's Day was nigh. As we walked and talked along the water's edge, the sinking sun rouged our faces, and I scanned the sand for seaglass. Having spent more of my lifetime on lakes than seas, I have always particularly appreciated the subtle, cloudy beauty of those glass gems. Rarity is perhaps why I love it ("lake glass" doesn't have quite the allure). But though not the rarest, of all seaglass colors, I most love blue. However, I care not for any color - even blue - that is merely factory-tumbled and sold by the bagful. Like dilapidated barns with tree branches stretching from the inside out, I am fascinated by the unintentional collaborative effort between man and nature that renders these jeweled treasures from former trash. Seaglass, found and picked from among seaweed and shells, is worthless and priceless all the same. That afternoon, as the sun slid further toward the cliffs ahead and my hand remained empty of seaglass, I mentioned to Darby how I loved the stuff, and that blue was my favorite. "But you never find it," I added, because it's true: you never do. Nowadays, glass-bottled beverages tend to come in brown, green, or clear. That old light blue apothecary glass is just not used enough to end up back in the sea, breaking apart and tumbling smooth for new lovers combing the beach on a random Sunday, even on the cusp of Valentine's Day. A moment later, Darby plucked something out of the sand and placed it in my palm. "Sometimes you just need to say aloud what it is you're looking for." Since then, seaglass, and especially blue seaglass, has come to represent to us both the essential importance of being consciously aware of what we are looking for in this life. It is not enough to complain about a lack or to vaguely desire some unacknowledged change. As individuals and as partners, we have to communicate to ourselves and to each other what it is we are looking for. Frequently, whatever it is is simply there at our feet, waiting for our eyes to notice. Glass Beach, we read in an article years ago, is thick with naturally tumbled glass from the confluence of ocean currents, rocky coast, and last century's practices of dumping trash into the sea. In the pre-plastic era, much of that trash was glass that broke and tumbled in the waves. We hear that visitors could once take big pieces home by the bucketful, but everyone tells us, "It's not like that now." I'd love to tell you about the whole trip, but I'll end this letter here: Remembering Duke Ellington taking the train, Joni Mitchell and her ladies of the canyon, Kerouac and Cassady on the road, people always say the heyday is long past. It's hard to see the heyday when you're in it, I suppose. Yet, as musicians and writers, Darby and I have lived our whole lives hearing the pessimistic stories of naysayers who say the best days for [fill in the blank] are gone. I call it hogwash. The best moments go up in smoke when you let others douse your fire, whether you're burning for travel, career change, taking a chance on your art, or falling in love. Half the time, though, you've just got to get clear and say what it is you want in this life, write it down boldly, and speak it aloud to another. And then you've got to go to Glass Beach, metaphorically speaking or otherwise, because it's bound to be more abundant in seaglass than anything you've ever seen. We had a hunch it would be a wonder to behold. Glass Beach, Fort Bragg, CA (photo credit: Darby Orr) Mendocino, CA at sunset (photo credit: Arielle Silver)

|

Archives

May 2019

Categories

All

|