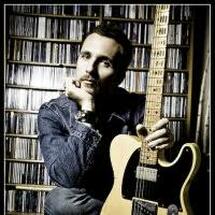

Shane Alexander Shane Alexander Last night after work, I drove out to Thousand Oaks for another pre-production meeting with Shane Alexander, who will be producing the record. If you don't work in music, the roles can sound mysterious. Using film as analogy: as songwriter, I'm like the writer of the screenplay. I craft a story in exactly the way I want to tell it, creating structure through the placement of every word and melodic motif. Since I'm also the artist -- the vocalist who performs and embodies the songs -- I'm like the lead actress, evoking emotion through my enunciation of the words and the timbre, volume, and expression of my voice. The rhythm of my guitar, whether it's strummed or finger-picked, with chords or individual notes, supports my voice and the story. The producer in a music project -- in this case, Shane -- is analogous to the director of a film. Listening to my vision and my particularness as an artist, Shane's role is to build the sonic world that will support and best showcase each song, my artistry, and the complete album as a whole. Last night, up at Buddhaland Studios, Shane and I more or less finalized the 7 songs for the album, plus discussed 1 or 2 other songs that might be released as separate bonus "single" tracks. Playing to a metronome, we ballparked the tempos and jotted down notes about Hammond organ, pedal or lap steel, shaker and tambourine, French horn or clarinet. As he said, I have a "rock bone," which is true, but a few of our favorites are definite ballads.

It's a funny thing to stand on the edge of a future with someone who you know will be important in your life. Songwriting, at least the way that I do it, is very personal. It's not just the lyrics of the song or the expression of the melody, but the backstory of what went into the song, the process of carving it into a shape, and the scraps left on the work table when it's done. It's also a lifetime of music rooted in the folk revival of the '60s, with long years of orchestral and renaissance ensemble playing, kirtan music, and puzzling out songs on my guitar. Shane and I have never before worked together. In our hours together these past two weeks we've been studying each other's artistry and work philosophy. To get to the final product, he and I will be engaged together in every step of the process. We need to know that we can trust each other, that we can communicate, and that aesthetically we're on the same page. I noticed last night that we're beginning to understand each other's language. Eventually, we'll know the shorthand, probably talk in music as much as words.

0 Comments

Last week, I caught one of those unwanted autumn colds that blows in unexpectedly just as the days warm for a quick Indian summer rebound. Being of hearty stock, I figured it would run its course and be gone by week's end. Instead, it settled into my chest, clenched my voice into a scratchy rasp, rifled through my schedule and canceled my weekend plans. Sunday and Monday were all tea and cough drops, but on Tuesdays I'm down at the college to teach, and by Wednesday my voice was entirely gone. Friday night had a gig scheduled, one that I'd been greatly anticipating not for its glamour (since, on the back patio of an urban bookstore, it certainly had none), but because I planned to sing new songs in front of an audience for the first time. With my voice shot, I couldn't rehearse, and as Thursday turned into Friday, I didn't even know if I'd have enough voice to sing on stage.

The last time I lost my voice, it was metaphor. I could talk and sing, if I wanted to, but I lacked the desire. The sudden desire to not sing, after years of desiring the opposite, took me by surprise. I tested myself time and again, played a few gigs here and there, to see if I'd really lost it. Eventually I stopped trying; the desire was inexplicably gone. With nothing else to do, I practiced a lot of yoga and took up running. I noted with curiosity the cycles of fruit, leaves, and clouds in southern California's subtle shift of seasons. Those changes might have escaped my observation if life had been louder, and my quietude also revealed gaps in some of the foundational logic on which I'd built my life. My former marriage fell away. As inner listening tends to do, I developed new awareness of my own inner workings. I became accustomed to silence's hard questions, and learned to endure the disquieting geological time scale in which difficult answers are disclosed. Among other things, I discovered, for the first time, something in myself resembling trust or faith. I wondered, during those years of silence, if I would ever come back to writing songs, if I would ever again want to sing them. They say that the Universe will test you. It will throw obstacles in your path to check your dedication to the thing you appear to want. How bad do you want it? the Universe will ask, and if you crumble and skulk back to your room, the Universe will have proven its point. That's what I thought, it will say. But if you really want it, you dig deeper. You find a way to get over, get around, or work with the obstacles. And the Universe will sit back in its chair and say, Oh really? Now look at you, kid. Tenacious little thing, aren't you? After a long decade of weird absence, the desire to create music returned to me. Maybe I needed that time to attend to rebuilding my foundation. Maybe I needed to find some faith. While I did that, my voice had run off on sabbatical. It's reappeared now full of stories from its travels, and for the last few months I've been writing those stories into songs. When this cold swiped my voice, I considered canceling the gig. Especially on Thursday night, I began to contemplate how I might contend with things if my voice never returned (oh, how illness turns me pessimistic). But on Friday I woke hearing the Universe asking, How badly do you want it? The information age! What a difference it is, starting out as an indie musician (as I feel I am doing, once again) and being an indie musician in the '90s / '00s. Back when I started playing gigs, we collected names and street addresses for our mailing lists, and mailed out postcards (with stamps!) every month to our fans. The way people got "free" music back then was by riding the subway -- and hearing the buskers play on the platforms.

Lately I've been appreciating the number of resources that are now available to indie artists. It can be overwhelming, so I thought I'd share a few of the rabbit holes I've been running down lately. If you have others you think I should know about, email me and I'll check them out. WEBSITES / COACHING / SERVICES

PODCASTS

In my early adulthood, with aspirations not for wealth but for creative fulfillment, I disciplined myself to live down to the bone. I nurtured thrifty tastes, saving my dimes for guitar strings and reeds. With my vegetarian diet, I shopped frugally, buying from the bulk bin, shopping in season and local, for a time splitting a $200 monthly rice and beans budget with a friend. I did not drink much alcohol, did not frequently dine out, did not indulge in fancy coffees or convenient sandwiches, did not buy frivolous clothes. Glad to finally enroll in what I fondly call Hogwarts School of Music, in my first semester at Berklee, instead of scrounging together $75 for a light-weight guitar gig bag, I drilled holes in my heavy hard-shell case and fashioned it with thick piano moving straps into something I could wear on my back. It was heavy, very heavy, particularly with my clarinet and laptop slung over my shoulders. I walked or took the T everywhere, and my back bent under the weight. In a recent newsletter to you, I wrote about raking up backyard leaves in a forgotten spot behind the garage, and my nascent vision of a cabin where I could practice my clarinet, try out song ideas, and work on essays and poems. It's been ages since I've had a room of my own, as Virginia Woolf wrote. I have long wished to sit in a windowed room and stare out the door at pale leaves as they unfurl into spring. I have wished for a room strong enough to withstand a thunder of ideas, because I have lately increasingly felt a rumble rolling through my heart, a heady mix of sound and emotion, art and media, questions and exploration. But I also wrote in that letter about fear of failure. I was worried about wasting money on something so specifically made by me for me. It felt a little arrogant: a playhouse for a grown woman who thinks she's got some talent or ideas worth the expenditure. What if I stepped into that arrogance, that audacity of hope (as Obama says), and nothing, in the end, comes? My fear might be rooted, in part, in an old Jewish superstition of the evil eye: If I do something so bold as build an artist studio just for myself, the heavens may train their unwanted attention on me, bringing tragedy to me or my loved ones. I should spit three times and hang a blue hamsa on the door. My frugality (always for my own desires, contrasted sharply, I hope, with my generosity for others) might also come from the valorization of parsimonious rationing in New England, where I lived for college and music graduate school, but whose culture I had admired since childhood. It suited the environmentalist in me: reduce, reuse, recycle. What throw-away materials might I re-fashion into use? How can I avoid purchasing newly manufactured goods, with their accompanying industrial waste and unneeded expense? But I bent beyond logic under the weight of that guitar case. I hadn't yet read Coleridge's The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, but I rued the albatross around my neck. The irony of it: that in my mid-twenties, finally glad to be at an incredible school and immersed in the study of music, I felt my instrument was a psychological curse I was tasked to bear. It took until my early thirties to examine the cliche of suffering for my art. Till then, I had accepted carte blance the stereotype of the starving artist. Looking back, I realize how easily I could have found $75 for a gig bag, saving my shoulders and neck a little of the physical pain that inevitably comes from the weight and repetitive motion of playing instruments. But I wanted so badly to be an artist, and from the stories I'd internalized, I thought suffering an essential part of a creative life. Fast forward to the past seven years, since Darby and the girls and I moved in together. It's a sweet house. Darby and I often say how glad we are that it isn't bigger. We want to stumble over each other, and engage with the teenagers even when they may prefer to sequester themselves in far off corners. The downside, though, is that I sometimes want to sequester myself away. As a musician, I need to make noise in order to get to the music. I am a lyrical writer, even in my prose, and tend to speak aloud every word as I write (even this, now). I've longed for a dedicated place where I can excavate my artist heart. A room of my own where I can throw ideas around, many ideas, because a good idea is not something that happens in isolation, but rather, comes out with dozens of bad-idea siblings. I've been yearning to throw spaghetti on the walls (I just love that phrase, don't you?) because something must eventually stick. Right? But what if nothing does? In this world of art as commerce, I have feared that the cost of building a little shed for myself won't find a return on the investment. And then I came across a passage in Elizabeth Gilbert's book Big Magic, where she writes, "Let me list for you some of the many ways in which you might be afraid to live a more creative life." This one struck hardest: "You’re afraid that someday you’ll look back on your creative endeavors as having been a giant waste of time, effort, and money." If a friend came to me with an idea, I would urge her to pursue it, to see where it will lead. In fact, after I wrote this post here, I heard from a number of you. Go for it! you said. The compounding encouragement was astounding. Your words amplified a desire deep inside me. So, this is all to tell you: I did it. It's a rule of cabins to have a name: Welcome to Seeds & Thunder, where on a daily basis I meditate, write, play music, and watch the pale leaves unfurl. Just some music things I've been into:

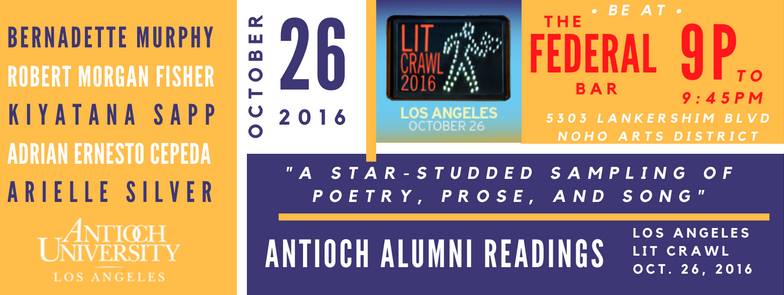

Podcasts: I'm super excited about 3 music-inspired podcasts: Song Exploder dissects the writing/production process. Check out their episode list or skip right to St. Vincent dissecting "New York." If you like to get super nerdy over lyric/music prosody, check out Switched on Pop (try the episode on Kacey Musgraves's Butterflies). And though the solitary episode of Broken Record, with Rick Rubin and Malcolm Gladwell, makes me wonder if it was a publicity stunt, Eminem is a master of phonology, and I loved listening to him talk with DJ Double R, and Gladwell as they dig into Walk on Water. Bands: I'm With Her is a bluegrass super group. For years I've been a fan of Sara Watkins, Sarah Jarosz, and Aoife O'Donovan as individual players, so couldn't be happier to hear their lush, earthy harmonies all together. Check out their website to see their NPR Tiny Desk Concert. For more on the band, read this. To calm my nerves and prep my mind for my performance tonight as part of the Los Angeles Lit Crawl, I invited my office colleagues into the pool room for a noontime 10-minute flash concert. It's actually the mail room, but a few years ago the company painted the walls Persian blue, put in new carpet, and installed a pool table and video game console. I'll deliver a song and a short story, I told them, and added that their presence would be a great service to me, as I haven’t performed in front of an audience in quite some time. It's actually been years since I've stood on stage and performed one of my songs. The invitation came from my hope to ease today's tension of what has been the duality throughout my life. On one side, my desire to sing, tell stories, and connect with an audience. On the other, nothing scares me more.

When: Today at Noon for 10 minutes Where: The Pool Room What: A Quick Practice Run of Tonight’s Song & Story Who: Me and You Why: Because, hey, it’s the entertainment business My earliest memories of singing are a collage: bath-time duos with my guitar-strumming dad; "Tomorrow" at the top of my lungs from the balcony at a Broadway show of Annie and, later, from the balcony of my grandparents' highrise; and, in Hebrew at my Jewish summer camp, "I'm Gonna Wash That Man Right Outta My Hair." Sometime between baths and camp, I learned shame and fear of being shamed. I internalized a philosophy that, at its essence, suggested that anything less than perfection was unworthy. Society? Parents? My own nature? Who is to say where I learned it. Stage fright is a bully. But I have songs and stories in my heart, and I am certain that if I don't answer their call, the incessant knocking will drive me mad. The anxiety was never as bad in orchestra and small chamber groups. I played classical and renaissance music from a young age through my mid-twenties, and frequently sat as first-chair in the college and community groups. In orchestra and wind ensembles, inevitably a solo line popped up here or there. I'd fret over those measures for minutes before they came, but I loved the sound of my singular clarinet soaring over the other winds and strings. Sitting in my formal black and white attire, I could be heard and not seen. When the momentary solo faded back into the wash of music, my nervousness calmed. I was just a vessel for the music amid the other players and a clutter of music stands. In my last year of college, I won a prestigious competition hosted annually by my university's music department. As the winner, I would be the featured soloist at the spring orchestra concert in an orchestral piece of my choosing: the Weber Concertino for Clarinet. Even more than the honor of winning, as soloist I had, for the first time, the opportunity to perform alongside an orchestra. Whereas in the past I'd only had piano accompaniment, for this I rehearsed alone and, later, in the concert hall with the full orchestra. In the throes of stage fright, I can never think clearly. I rehearse to perfection beforehand, in the hopes that in the moment I will be able to deliver a large fraction of that excellence. But rehearsal is not fear-proof. On the day of a performance, my stomach churns for hours, my legs feel numb. On stage, I sweat, I shake, I forget how to do the very thing I have practiced to flawlessness. But I fake it in the hopes that one day I will make it without fright. Unsurprisingly, as the days led up to the concerto performance, I was a wreck of jitters. I knew the concerto competition concert would be the most well-attended of the year. My parents and grandparents, none of whom later attended my college graduation, all flew in. A few days before the concert, I confessed my nervousness to my mentor, Sarah Mead, a beautiful viola da gamba player who had introduced me to Early Music my first semester and nurtured me through all four years like no one ever had. Sarah and I had both skipped grades in elementary school, and bonded over the lifelong sense that we'd missed some essential lesson only taught that particular year. She introduced me to the beautiful music books of the renaissance, with their four lines of music facing the four outer edges so that a family could sit around a table after dinner and play music together. Sarah knew I loved a challenge, and whenever our Early Music ensemble called for a new instrument, she gave me the task of learning: recorders, harp, krumhorns, flutes. Later, after I graduated, I couldn't bear to leave Sarah, so I continued to commute to campus for weekly rehearsals, until I finally moved away. The week of the concerto performance, Sarah told me about the first time her son Patrick played piano for an audience. He was around seven, and he was to play a solo piece as part of the university's celebration of composer and music department founder, Irving Fine. Sarah had worried about his nerves, but when she woke Patrick on the morning of the celebration, he sat up in bed with wide eyes and big grin. "Mommy," he said, "today's the day I get to play my song for everyone." That Sunday, while the orchestra played through the first half of the program, I sat in the green room smoothing my dress and repeating Patrick's words. "Today's the day I get to play my song for everyone." I thought over and over, my fingers shaking on my clarinet keys as I ran through arpeggios, my empty stomach clenching. "Today's the day I get to play my song." I heard the applause and walked onto stage. "Today's the day." I nodded to the conductor and he lifted his arms for the string opening. I am tempted to write more, to tell you how I wet the reed, how my first note rang in the hall, how playful the theme and variations felt tripping off my fingers, how the orchestra buoyed me, how the cadenza I'd written for the near-end felt like a braiding of my own music with Weber's. I am tempted, but I can't, because I don't remember any of it. I only remember feeling a profound sense of shame at the end. Nothing terrible had happened -- I didn't forget a line, my clarinet didn't squeak -- but I remember afterwards wanting to hide from the family and friends waiting in the hallway with bouquets in their arms. For years after that concert, I hid my accomplishment -- the competition, the performance -- convinced that I'd not deserved the recognition. Perhaps that year the competition had been slim. Perhaps I, a far cry from the winners of years past and future, was only the best they had that year. It should have been a glorious moment, a capstone to years of practice and study. But all I could think was that I'd had one chance for perfection, and I had not achieved it. Not long after, I packed away my clarinet. Meanwhile, sometime in college I started writing and singing songs. I wanted so badly for someone to listen, so after college I met my fright head on. I wanted to capture Patrick's joy at sharing something that he loved with others. Following the footsteps of my juggler boyfriend, I bought a busking permit at the Cambridge city hall and every weekend plugged my two-input amp into a car battery, laid out my guitar case for tips, and played for passersby in Harvard Square. When the air turned cold in early October, I donned a winter coat and fingerless gloves. When the Head of the Charles tourists left town, I turned to open mics at Club Passim, the Kendall Cafe, and other songwriter venues that have since closed. Over the years, I pulled together a band, I recorded, I toured. Stage fright still gnawed, but I fought it with a combination of coca cola and gin, and the frequency of performing forced my anxiety into a tenuous remission. And then, ten years ago, I stopped performing almost entirely, and stage fright became a thing I know about myself but didn't have to face on a daily basis. The songs no longer wanted singing, so I no longer needed a stage. My guitar joined my clarinet, and though I occasionally I strummed some chords, for the past ten years I've not felt any great urge to perform. Until now. I woke this morning with wide eyes and a smile. I cannot explain this excitement: I haven't felt it in years. My hands are shaking, and my stomach is churning, my legs are numb, and I'm afraid that despite my practice, I won't be perfect. But beyond all fear, tonight is the night I get to play my song, tonight is the night I get to read my story. Me in the pool room: Ten years ago I stepped off the stage, packed up my guitar, and sat beside the Chesapeake Bay with a skein of yarn and circular needles. I had no idea how to knit, and I had no idea how to live with or without music as the central focus of my life. For those 6 weeks, KT Tunstall and the click of my needles were my soundtrack. I took walks on the empty beach and dragged giant driftwood logs back to the house. I tried writing a song or two, and drenched my guitar with tears. I knitted eleven purses. I listened to KT, a rockin' folker / folksinging rocker, a woman exactly my age who had less fear and more energy. I found some comfort that she was "making it" just as I was stepping away, almost like we were alternate versions of the life i once wanted. I never went back to performing, not in a full hearted way, but she's still killing it, and last night at the Fonda she rocked my world.

A writer friend of mine recently shared a video about self-publishing. In the tumult of a changing literary industry, among writers, traditional publishing versus self-publishing is a constant conversation.

Having not yet completed even writing a full-length manuscript for publication-consideration, perhaps my two-cents is a little premature. Yet, as a former (and possibly future) recording and touring musician, I would encourage any writer to think critically when considering whether self-publishing is the way to go for their own work. I applaud those who, now or later, answer "yes" to that question. I imagine it's a brave and exciting path into new territory, particularly if the endeavor is successful. But I would argue, based on my career as an independent recording artist, that there are compelling reasons to forgo the independence, and spend the time and effort seeking agent and publishing house representation. While these questions of self- or traditional-publishing are relatively new to the literary world, they have been going on in the music industry for a while. In the seven years between the recording of my first album and ending my last tour, I recorded, promoted, and toured without help from a major record label. The first album was on my own LionsRoar Records, and the other two were with a small, wonderful Boston-based label called Passion Records. The benefit of working independently was that, from an artistic perspective, I retained all control of my music. I still hold 100% of both writer and publishing shares of the copyright, and no one ever sent one of my songs to the chopping block. Of course, as an old music business teacher once told me, 100% of nothing is still nothing. In fact, after all the recording, promotion, and tour expenses, 100% ownership came to less than nothing. It turns out, credit card statements don't stop when the tour ends. As a musician without the distribution, radio-influence, clout, or marketing campaigns of a major label, I lived in a van with my band, drove from small venue to small venue, sold discs from the edge of the stage, slept wherever I could score a spot. Sometimes it was in a relative's spare bedroom, many times at club-owners' houses, a time or two with "fans" a/k/a strangers we met during the soundcheck, occasionally in the bartender's cigarette smoke-filled living room, and once, in Milwaukee, on the beer-soaked carpet of the very club we had played earlier that evening. That was the touring. Weekends, holidays, vacation time, and, in the last year, when we mustered the courage to quit our jobs and go out full time. The recording was another matter. It was done after-hours, in the tired times between full time jobs and school. I learned Photoshop so I could design the CD covers. I learned how to make press kits, and stopped at the post office on my way home to mail them to radio, magazines, and venues. What I am saying is that being an independent artist trying to make a viable career is ridiculously hard work. Every independent artist is inventing their own wheel. While I wouldn't trade my life experiences for the world, I wouldn't do it again. It's a 20-something game, not a 30- or 40- or (holy crap) 50-something game. If songwriting was the art I loved, it was also the thing that got squeezed out between radio promotion campaigns, all the waiting between soundcheck and load out, and the long drive home. The whole endeavor of being an independent artist means a lot of hustling for a little money and, more importantly, a small listening audience. The question is, is the goal to be published or to be read? As a songwriter, I wanted to be heard, but for a long time confused this with wanting to simply perform and record. It took a long time before I realized that there is a difference. As writers, do we want to be published? Or read? We're all just figuring it out, one song, one word, one piece of advice from a trusted source at a time. Unless you're in line for medical school, there is generally no one path to achieving a professional goal. But it seems that emerging writers who are not celebrities, who are not already established authors, or who do not already have a wide fanbase of readers, probably don't have the marketing power and industry wits comparable to even a small publishing house. I'm not saying it can't be done. I believe everything can be done. But from here, of the two very difficult paths to gaining readership, the self-publishing path looks to be the harder one. Of course I haven't gotten that far yet. I'm just beginning the second draft of my book-length manuscript. But right now, from the safety of my desk which is beautifully free of rejection letters, I believe the time and energy we invest in querying literary agents and mailing out manuscripts is a worthwhile investment. If we can't get our books read by prospective agents, we'll have an even harder time getting them read by reviewers and the general public. The point of the initial gatekeepers is so that, once they accept us, they represent us to the next level of gatekeepers. Each rejection we receive from an agent is an invitation for possible revision of our work, hopefully strengthening it as we go. This is not to imply that those of us who choose the traditional route won't undertake marketing efforts. We will. Twitter. Facebook. Instagram. Reddit. Tumblr. Oy. That's another popular conversation/lament among writers. But it won't be a solo effort as in that of a self-published writer. The publishing house will effort on our behalf. The gatekeepers beyond our reach might be reached. And from where I sit-- which is across the room from my guitar, a stack of left over tour posters peeking out from under the coffee table for the kids' art projects--the support of an agent and a publishing house looks glorious. This piece originally appeared in the online journal Lunch Ticket on September 12, 2014: http://lunchticket.org/courage-it-takes/ Sitting under a café umbrella recently, sipping iced tea with an MFA colleague, the conversation naturally, unsurprisingly, turned to writing. We’re both in our second semester of graduate school. As I’ve mentioned previously in this blog, I’m “Creative Nonfiction.” It’s a fact which never ceases to amuse my fiancé who takes it as an existential statement. My tea-sipping friend is “Fiction,” which amuses my fiancé even more.

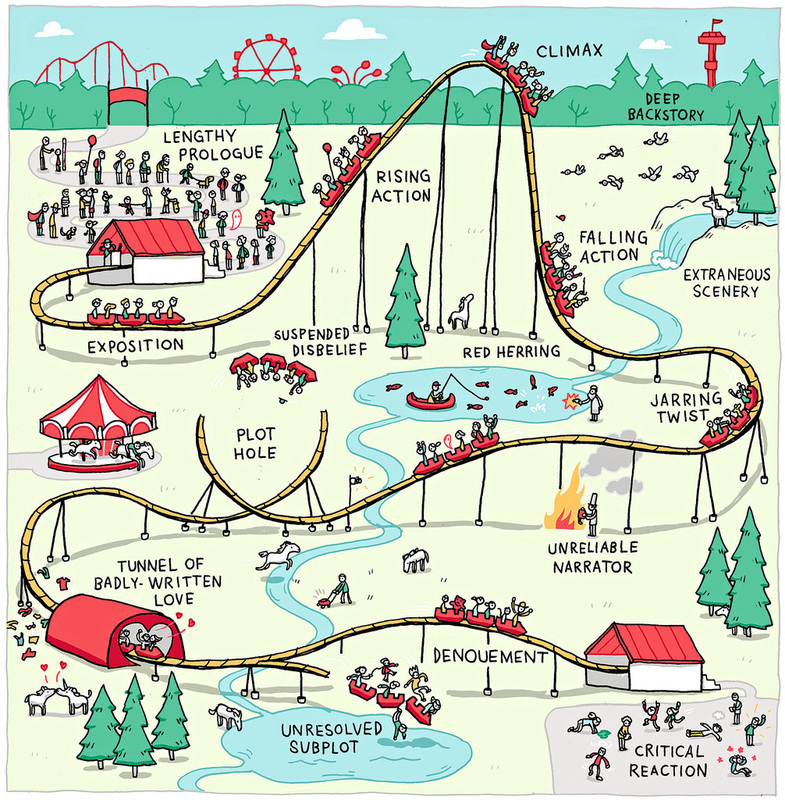

Regardless of fictive or nonfictive embodiment, my friend and I both agree that the monthly packets we are required to submit to our MFA mentors are very real. Troublingly so. My most recent packet of twenty creative writing pages and two book annotations was due to my mentor in mid-August. For two days afterwards I celebrated its completion by not writing a single word (status updates and margin notes inBehind the Beautiful Forevers, of course, aside). On the third day I intended to get back to writing, but—nearly a week earlier than expected—I received my mentor’s return email: a detailed letter, in-line track change comments, and lecture notes on a particular topic she suggested I study. I was paralyzed for a full week afterward. Could. Not. Write. Anything. I sat with my friend at the outdoor café during that time. It was one of those blazing hot Saturday afternoons when everything melts: ice in our drinks, lipstick in my purse, ego. We sat together, pulling our sweat-soaked shirts away from our backs, fanning cigarette smoke from the table next to ours. Inside the café, the A.C. was on full blast but the room was crowded with chatter, and she and I both had some things to get off our chests. She, too, had a hard time getting back to work after sending off her last packet. “I’m afraid of criticism,” she said. It was powerful to hear her express what I had been feeling. Of course criticism—particularly at the hands of a knowledgeable and supportive mentor—is meant to be helpful. Indeed, it’s a primary element of why we both came to this program: to receive critical feedback about our work. But the fear we associate with criticism is attached, I think, to shame. Shame that the basket we’ve put our eggs in is full of holes. Shame that we will fail. Shame that there is a right and wrong to writing and that, ultimately, it is just beyond our personal abilities to get it right. Fear that we are not capable of stepping into our highest creative self. My friend’s reflection of my own fears was enough to remind me of a time, years ago, when I had not allowed my fears to stop me. After years of studying classical music, sometime in college I ended up with an acoustic guitar and a book of folk songs. Joni Mitchell, Pete Seeger, etc. I had been raised on these songs by a guitar-strumming dad. My first concerts were folk festivals where my parents spread a blanket and we picnicked on my mom’s cold fried chicken and berry pies. The folk songs in the book hit a deeply personal spot from my earliest childhood memories. It was a place that classical music, as much as I loved it, had never tapped. The book was a doorway, and when I walked through it, I walked away from classical music, stepped onto a path of songs, and, shortly, started writing my own. Right away came the desire to sing for others. A moment later, my stomach clenched with fright. Stage fright, like fear of criticism, can be debilitating. It can also be exhilarating. I’m not a fan of roller coasters, but I wonder if the draw to them is similar. Do coaster-lovers shake in fear? Do they wonder if they can handle it? Do they get a rush from the courage it takes to ride? This is what it feels like, for me, when I send in my mentor packets. I silently beg, as I hit send, that my mentor’s feedback will be enough to kindly push my edge, an edge just shy of disablement. Often, to work out fears that arise in my new(ish) writing endeavors, I look back to my life in music. How did I overcome my life-long stage fright so that I could pursue my love of singing and songwriting? I showed up. Back then, I was up against all these same fears of failure and shame, but my desire to get better at my craft was larger than my fears. I knew the only way to improve was to do it. Perform. As much as possible. The solution? I joined the busking world. I didn’t have to wait for a club booker to let me in the door. I could pull up a piece of sidewalk and play every night, which I did throughout summer and fall until my fingers froze, and then again the following spring. There was a good community in my Boston busking world days—Amanda Palmer, Guster, Mary Lou Lord, and many others who passed through for a week or for years—but also, I learned to stand up in front of an audience. I learned to show up against my fears. After a few hours at the café, our iced teas were finished, our conversation spent, our backs sweaty. I drove my friend several blocks to where she had parked. “I made something for you,” she said as she unlocked her car. From the backseat she pulled out a pale green cotton bag with two wide shoulder straps and a red and white swath of cloth down the center. I can’t sew at all, but I appreciate the craft. Her stitches were perfect. The muted colors were imbued with my friend’s gentle spirit. The kindness was almost overwhelming. Fingering the stitches of my friend’s gift, I remembered something an old teacher used to say: How you do one thing is how you do everything. I haven’t read my friend’s writing, not yet. Nor has she yet read mine. But I am certain that when the day comes for us to exchange not just our trepidations but our art, we will find in each other’s writing the level of courage, commitment, and care that we bring to our other arts and crafts. As with everything, sometimes fear stops us for a few days or a week. But always, every time, our desire to do this—to explore questions, share stories, to write—leads us through the turnstile and back onto the ride. |

Archives

May 2019

Categories

All

|