The new Winter/Spring 2017 issue of Lunch Ticket came out a few days ago, and the next day I stepped down from my post as editor-in-chief and passed the baton to my successor. Still, after months of working on pulling together this issue, I'm not ready to walk away. There're so many fantastic interviews, poems, essays, translations, short stories... Start here with my Word from the Editor and then pop over to the magazine: I began drafting this essay at the end of the presidential election season, in light of what many of us thought would be a landmark historical moment: the United States’ election of our first woman president. On November 8, as we are all too aware, despite winning the popular vote by (as of this writing) over two million, the Electoral College results tallied in favor of her opponent. Spurred by a campaign rhetoric that relied on a cornerstone of violence, fear, and hatred, the president-elect continues to provoke considerable domestic and international criticism. Shocked by what this outcome revealed—that nearly half of voters responded positively to his rhetoric—, many say that it appears we have two Americas, red and blue. Like warring tribes, we’ve now turned away from each other and returned to our camps, separated by a modern Mason-Dixon line in the divided states of America. We curl up with our own news sources, revel in our own truths. The fissure is too deep, we say, and so draw a line that relieves us of reconciling our differences, scrutinizing root causes, or compromising our values. Fissure is just one analogy to describe the state of the (dis)union. We could, instead, look at our picture of this country and say that part of our view was obscured. As political theorist Andrew Robinson writes, “Any particular way of seeing illuminates some aspects of an object and obscures others.” With our sights set on equality, community, and eco-conservatism, we now realize that we missed a large segment of the picture. Feminist scholar Julie Jung calls this synecdochic understanding: using part of something to represent the whole. As it turns out, many of us—including every major newspaper and pollster—were looking at the U.S. through this device. The election results lifted the shroud. Now we’re squirming in discomfort about two new sources of awareness: that which was underneath the shroud and the shroud itself. As long as there’s a shroud, the former cannot be helped. But we should question why we didn’t investigate our blind spots, why we overlooked the shroud. Often writers think of revision as a task grudgingly—or happily—undertaken to perfect our work. We reread our words seeking moments of disconnect for the bits that don’t seem to belong, and we assess their worthiness to the story. We want our work to make sense, so we seek a narrative arc. If something doesn’t propel the narrative or make consistent sense for a character, it falls to the cutting room floor. Smooth out the wrinkles, wash out the stains, turn in the essay, get an A. But what if we revised revision? What if instead of smoothing out the wrinkles, we held them to a magnifying glass? In this approach, so-called flaws would not to be brushed away but, rather, probed. As writers, artists, and activists, can we approach our work so that revising—that process of looking closely at our work for moments of disconnect—is not a process of glossing over but of examining more closely? Instead of manipulating truth in service of a smooth narrative, we should examine our motives for creating a smooth narrative to begin with. In this light, revision becomes not an act of making something flawless but, rather, making it more whole. As Annie Dillard writes in Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, “Go up into the gaps. If you can find them; they shift and vanish too. Stalk the gaps. . . This is how you spend this afternoon, and tomorrow morning, and tomorrow afternoon.” Given this approach to revision, what cultural material have we rushed to brush away before truly exploring? In our attempts to move toward equality and understanding, it’s now apparent that we’ve not fully attended to the underlying bigotry, misogyny, and xenophobic ills that this election season oozed to the surface. We have a country half-peopled by those who either resonate with or can overlook narratives of distrust and resentment for “the other.” Although it feels for many that we’ve now taken six decades’ worth of steps back, perhaps the reason we need to do so is because our progressive vision glossed over too many foundational cracks. While we were moving forward, half the country planned a revolt. If we’re committed to walking our talk of inclusion, then we need to hunker down in this new climate to revise our understanding of the United States and build something more tenable. It was with these thoughts that I have been turning the pages of our tenth issue, which is my last as editor. It appears to me that what we’ve put together here is a multi-layered, multi-genre conversation about gaps in cultural narratives, moments of disconnect or desire for connection, and an attempt to, as Dillard wrote, stalk the gaps. If anything, the eighty-two pieces in this Winter/Spring 2017 issue, from interviews to art to new and translated work in fiction, poetry, and nonfiction, point to the value and necessity of open discourse, of reading the white space between words along with the words themselves. In her interview for our Lunch Special, Maggie Nelson says “every draft is slathered with self-deceptions,” which we must examine in order to get to honesty. In a separate interview, artist Harry Dodge responds to Nelson’s The Argonauts by reminding us that “any piece of art, whether nonfiction or otherwise, is a construction” and asks “whether language is able to do the work of describing fluidity, or anything really.” In his interview, poet Fred Moten talks about how writing should not suppress what he calls the monstrous, the strange, the radically disruptive fundamental aspects of life. And Susan Southard says of Nagasaki, a braided nonfiction narrative about the U.S. bombing in WWII, “I felt it was so important to bring [the survivors], still hidden from view in our country, into visibility.” This theme of visibility is stitched throughout the issue. We could say the stitches are like sutures, repairing cultural wounds, but the stitches are also like hand-sewn needlepoint, each threaded with its own palette, in its own frame, its own unique picture. Gabo Prize winner Jim Pascual Agustin’s poem Danica Mae is about the recent mass killings in The Philippines. Diana Woods Memorial Prize winner Sarah Pape’s CNF piece Eternal Father & The Other Army brings to light a nuanced experience of depression. Call to Arms, Marine Lieutenant Lisbeth Prifogle’s featured essay, is about the need for publishing “stories that could alleviate the fear, isolation, depression, and anxiety of joining the old world after a deployment.” Grace Lynne’s featured art collection, The Exploration Series, seeks to show “Black culture in a new light, and open people up to a side of my culture that they haven’t seen.” I could, without reservation, list every single one of the eighty-two pieces in this issue. It is a beautiful, heartbreaking, mind-expanding collection, and an honor to publish this one as my last. After three issues as editor, this is a bittersweet goodbye as I now step away from the journal. My studies in the Antioch MFA program and, recently, as a Post-MFA in Pedagogy student are nearly complete, and Lunch Ticket has and always will be student-run. My work leading the editorial and production staff, reading our submissions, developing relationships with our writers and artists, and connecting with literary and art lovers who come to our pages has been humbling, inspiring, and invaluable for my personal growth as a writer and as a woman in this world. Thank you for being here, for sharing your stories, for reading ours. And take good care, Arielle Silver Editor-in-chief, Lunch Ticket

0 Comments

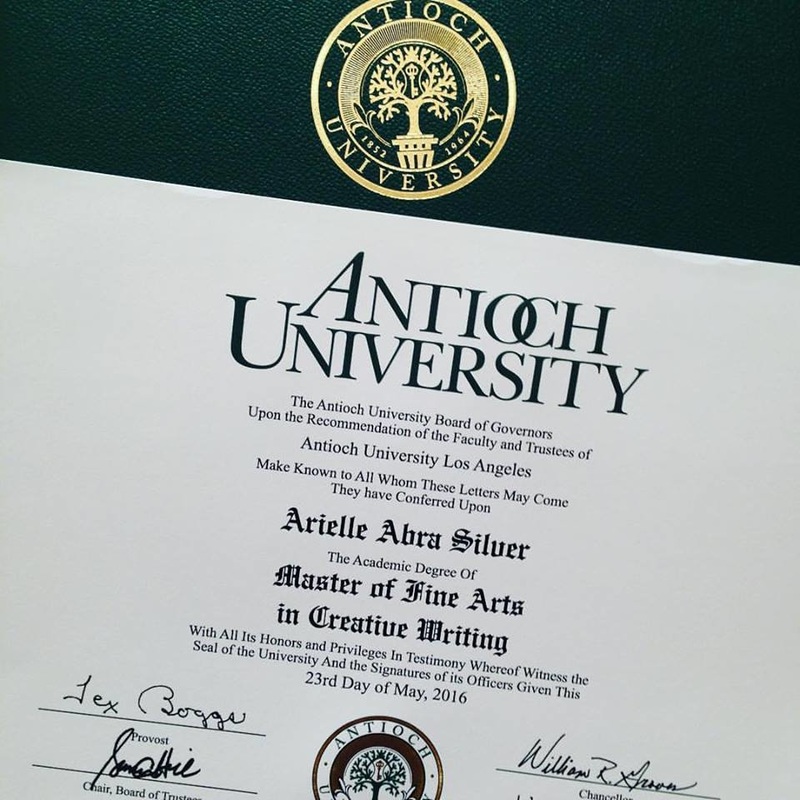

I ran off to Big Sur last week, and when I got home, this was waiting on the doorstep. I want to write a whole story about it - it's an MFA in Creative Writing, after all, and after 3 years' journey through my primary study in creative nonfiction and secondary in fiction and literary translation, I should be able to string together some delightful narrative. But, truth is, while I've earned the degree, I'm still in the story. This semester I'm concurrently enrolled in a Post-MFA Certificate in Creative Writing Pedagogy and a Professional Development Semester in online CW course development. And as long as this is CNF, let's be honest: I won't be done with my PMFA Certificate till June. Also, I'm still serving as editor-in-chief of Lunch Ticket (and completely honored to do so), and still deeply entrenched in grad school.

But I want to sit still long enough to look at this degree in my hands, because I've worked my booty off these past almost 3 years. I've grown tremendously as a writer, editor, and teacher. I've written and rewritten a book-length manuscript four times, started work on a historical novel, studied French and translated a book and a half and some poetry into English, really studied the art and considerations of translation, have researched and written (and published) about the wicked stepmother trope, learned a great deal about the literary world and publishing an online journal, and have published a bit of my own work. I'm still fired up, and all of this is due to my incredible mentors and the support of the whole AULA MFA community. Never ending gratitude for the guidance and influence of these writers and teachers: Brad Kessler (Birds in Fall, Goat Song) Hope Edelman (The Possibility of Everything, Motherless Daughters) Dan Bellm (Practice, Description of a Flash of Cobalt Blue) Peter Selgin (The Inventors, Confessions of a Left-Handed Man) Peter Nichols (The Rocks, A Voyage for Madmen) Bernadette Murphy (who gets all the credit for getting me to apply to this program) (Harley and Me, Zen and the Art of Knitting) Sharman Russell (Diary of a Citizen Scientist, Teresa of the New World) Christine Hale (A Piece of Sky, A Grain of Sand) Jenny Factor (Unraveling at the Name) Audrey Mandelbaum and MFA program director, Steve Heller (The Automotive History of Lucky Kellerman), who for some reason continues to trust me with the keys to Lunch Ticket, And, lastly but most importantly, my dear husband Darby Orr, who served as my first editor, married me in the middle of this whole mess, and who has encouraged me every word along the way. "Trust in the synergy of the things that are coming together, and don't fret about the rest." – Amy Sage Webb My AULA creative writing pedagogy mentor, Amy Sage Webb, said the above last December in an exciting seminar I attended during that particular MFA residency. They say when the student is ready, the teacher appears; in that moment, I knew I would enroll in the Post-MFA Program in Creative Writing Pedagogy just to have the opportunity to study with Amy, who is also Co-Director of Creative Writing at Emporia State University in Kansas. What I didn't realize at the time was that it was a two-for-one deal with co-mentor, Tammy Lechner, a teacher and Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist - talk about synergy. Since mid-June, with Amy and Tammy and my small Post-MFA cohort comprised of six other writer-teachers, I've been in constant discussion about what makes a great teacher, what the best college teachers do to create engaging and stimulating learning environments, and how to bring these macro-ideas into the composition and creative writing classroom. We've discussing questions about authority, gender issues, learning theory, teaching philosophies, how to evaluate creative work, what higher education politics mean to our budding careers in academia, and how to develop learning objectives that foster discipline-related intellectual growth alongside personal growth in our students. Concurrently, I opted in for a double-wammy of enrolling in a Post-MFA Professional Development semester focused on book coaching and online creative writing pedagogy. With author and teacher Kate Maruyama, and writer and pedagogy specialist, Curt Duffy, alongside guidance from Amy and Tammy, I've been developing a community online writing course to teach later this autumn. The course idea comes from something I've been fired up about lately: weird writing structures, a/k/a lyric essay, a/k/a where poetry and prose meet. The course is meant to inspire first drafts of new work for seasoned and new writers alike, and will explore non-traditional forms to find inspiration from the mundane moments of every day. Since the course will be in feast-centered November, with my lifelong interest in cooking and food I couldn't resist adding a little twist. The course is called "Feasting on Form: Noodling Around with Experimental Creative Nonfiction." That whole month (the course is 4 weeks), we'll explore bite-sized ideas taken from grocery lists to lonely snacks to shared meals -- all ripe for narrative discovery -- and share brief essays that we write inspired by these moments. I believe some students will leave the class with solid drafts close to submission-ready for literary journals. I’ve frequently thought of Amy's words about synergy since receiving my MFA degree in June. As I query literary agents for my memoir, continue to lead the editorial team on Lunch Ticket, work through my Post-MFA courses, occasionally squeak out a new essay or a few words in my novel-in-progress, and plan the yoga and creativity retreat in January, I could wonder if my head-down work ethic blinds me to the viability of making a professional career of writing and teaching. After all, one agent who recently turned me down wrote, “I really like your writing—I really do!... but, I’ll be honest with you, I’ve had the shittiest time placing memoir lately.” But after repeating the synergy mantra since December, it comes unbidden now, and I truly believe it. I’m not fretting very much. I trust in the synergy of the things that are coming together – the retreat! My studies! My writing! It all feels too good to fret about. And in any case, I’m having fun. The other night, my writing group gathered for our twice-monthly meeting at my house. We've been meeting together for more than a year. Lately, my increased pedagogy coursework leaves little time for creative writing, so I depend on these friends to keep me accountable to my artistic side. This week I only had three pages of new work for them to read, but they were three pages I wouldn't have written otherwise. Inspired by my group’s feedback, I’ve already redrafted the piece and shipped it off to a literary contest. Before we settled into the meeting, one writer in the group confessed to me about feeling concerned about her future job prospects. She's about ten years younger but we've shared some similar life paths through music, writing, communal living, and honest day jobs. She asked me about the coursework I've been doing. Will it guarantee a job, she wanted to know. How can I answer that, after my strange career life: a touring musician, a chef, a photographer, an artist model, a newsstand clerk, an administrative assistant, a yoga teacher, a production supervisor at a music label? How do you answer a question like that in today's gig economy in which universities depend on adjunct faculty the same way for-profit companies avoid benefit payouts with outsourced consultants? But Amy Sage Webb’s words come back to me. I need to remember to share them with my writing group. “Trust," Amy says. By its nature, trust is about the unknowable, the uncertain. Trust is about things just out of sight, just beyond the bend, though not as far away as, perhaps, faith. Trust reminds me of the E.L. Doctorow quote, "Writing is like driving at night in the fog. You can only see as far as your headlights, but you can make the whole trip that way." When I’m stuck midway through a chapter of my novel and start fretting about where it might be heading, I think back to this quote. But it helps me even more when I lift my head from my school work. “Trust in the synergy of the things that are coming together.” The road is beneath the tires, I can see as far as November to the month-long writing course, and as far as January to the yoga and creativity retreat. Ten years ago, I didn’t have this kind of trust that things will work out fine, but perhaps, more than anything, that’s what the decade has taught me. This time next year? I have no idea. But I’m not fretting. Where we put our attention is how we define our reality. And like I said, I’m having fun. This piece first appeared in Lunch Ticket on June 5, 2015

http://lunchticket.org/a-third-path-in-the-mfa-v-nyc-debate/ When my brother was little, his bedroom was a minefield of broken things. He took stuff apart, wanted to see how it worked. Toy cars, radios. He was just as happy with hand-me-down junk from our grandparents’ basement as he was with something new from the store. It all had the same dismantling fate. Beware, bare feet. Bits of Hot Wheels in the plush carpet awaited a trespasser’s vulnerable step. The greatest gift to our family was a huge denim bag that closed with a bright red drawstring and, when fully opened, was laid flat in a gigantic circle. With the bag spread out on his floor like a round tablecloth, my brother could work happily for hours, and then our mom would cinch up the drawstring and stuff it in the closet. Easy clean-up and foot-friendly floors. There’s a debate in the literary world about the merits of attending an MFA program versus simply experiencing life and writing. (Here’s the book, a Slate piece, a New Yorker piece, New York Times,Salon, and a personal essay series on the topic at Zoetic Press.) I find the whole discussion fascinating, and it’s worthwhile not because there’s any right or wrong way to hone a craft, to develop an art, or to live a life, but because the robust discussion is like my brother’s parts-strewn bedroom floor. Working writers are taking apart their experiences, holding magnifying glasses to their lives, and offering advice to emerging writers. How did they build their writing life? Where did they learn to do what they do? What experiences gave the best bang for the buck? How do they make a living? What path do they recommend? So far, my eighteen months in AULA’s low-residency MFA program have been deeply gratifying. But, in my time here I’ve found a third path that offers invaluable experience for an emerging writer. If we’re talking about bang-to-buck ratio, hands down, the advice I’d give to any writer is the advice Antioch’s MFA program director, Steve Heller, offered to me in my first term when I came to his office and asked what I should be doing to support my interests in writing and teaching: find a literary journal, volunteer to do whatever needs doing. I’ve been serving on Lunch Ticket since a few months after that conversation, and do not intend to exit soon. I have found that the main qualities I seek in the MFA program—to develop as a writer, to develop skills and credentials for professional growth, and to connect with a community of writers—are deepened by serving on this journal. Lately I’ve been trying to sort out the reasons why. Here are a few: Develop as a writer. Like my brother with his toys, being a writer means taking things apart, trying to figure out how they work, or why they don’t. As a reader for the Creative Nonfiction submissions that come in, I’m always unscrewing sentences, holding a magnifying glass to the bits, shining a flashlight on myself, on my attention, on my reactions. While reading, I map the structure of a piece, take note of the style, voice, story. I discern levels of polish, and whether a piece feels complete, or if it still needs work. Reading for a journal is much different from reading already-published work. It offers the opportunity to read pieces from writers across a broad spectrum of skill and artistry. Much like how yoga is good cross-training for a runner, reading submissions is good cross-training for a writer. There’s as much to learn from pieces that don’t work as from pieces that do. Develop skills for professional growth. Like every shiny toy car that my brother dismantled, publications have a lot of moving parts. They’re all nuts and bolts on the inside, full of web pages and publishing schedules. I could have paid for a WordPress class, but being on the Blog team has provided hands-on learning. Being a reader on the CNF team has meant learning how to write clear analysis of a piece to back up my opinion of it, and to effectively discuss submissions with my co-editor and our assistant. Working with the copyeditors, and copyediting the Blog, has meant a sharper eye to typos, formatting, and grammatical issues. Being Blog Editor has helped me hone my developmental editing skills while working with the wonderfully varied voices of my fellow bloggers. Connect with a community of writers. Most literary journals are built and staffed just like Lunch Ticket—with writers. We all know the solo journey of writing, the lonesome company of sitting with our thoughts. Being part of a journal means having a lifeline to people grappling with their own solo paths. Here at Lunch Ticket, everyone struggles with time, how to balance art and life, how to write authentically, how to get over fears. We check in with each other, and every person on Lunch Ticketknows the hesitancy of a submissions button, the hope of an acceptance, the sting of rejection. We read each other’s work when it’s published, and share the links with our other communities. Corresponding primarily through email, half a year usually goes by before we see each other face-to-face. Still, we are connected, and we bolster our individual writing journeys through our shared work on the journal. Perhaps one of the most emotionally valuable benefits I’ve found is that working on a journal puts rejection in perspective. I imagine most journals want as many submissions as possible. We do too. Generally, the higher the quantity, the higher the quality. And yet the volume of submissions can be humbling. So many to read. And then I find an essay that floors me. I know the whole pile was so worth it just to find this one piece. I vote to publish it with a resounding YES, only to be countered by another reader’s tepid “hmmm.” We discuss it, and every time I am reminded that, when it comes to reading personal essays or poems or stories, there is no such thing as objectivity. What hits me with its beauty struck another as overwrought. Or my co-reader reminds me that we just accepted another similarly-themed piece a week ago. Sometimes, simple timing plays into the mix. So, too, does basic space limitation. We send the rejection letter, hoping that our careful wording buoys the writer more than it stings her ego. We are all that writer. We want to be buoyed up with hope, at least enough to send us back on that lonesome journey of sitting with our thoughts, writing them down, and sending them out. My little brother’s all grown up now. Like most older sisters, I am constantly shocked at how much taller he is than me. Who knows where that bag with the drawstring ended up. I imagine it was passed on to another kid when my brother outgrew it. I am tickled by the thought that now, decades later, the bag might be spread on some kid’s bedroom floor, holding all the components of a toy car so that after she tears it apart, it can be put back together. This is what I’m hoping for myself also, from my time atLunch Ticket. That this opportunity to unscrew other writers’ sentences helps me put together my own. That learning the nuts and bolts of this journal gives me courage to submit to others. And that long after I receive my MFA diploma, Lunch Ticket stays cinched together, continuing the community of writers, because we buoy each other up. These past five months I've been honored to serve on a literary journal - Lunch Ticket - as Blog Editor. This week, in particular, I am reflecting on how special the writer/editor relationship is, how much I've learned in this role, and how appreciative I am that my writers have been so willing to work with me (and each other) in this way. It is beautiful and humbling work.

All artists know the ego-challenge of handing their creation to someone who intends to review it with a critical eye. An editor searches for missing commas, redundant phrases, and awkward wording, but they're also reading closely to be sure all the sentences *belong*. Sometimes the opening line doesn't grab. Sometimes the last line is lukewarm. No matter how much time a writer has spent crafting it, sometimes an entire paragraph is simply in the wrong essay, the first page just a throat-clearing, a warm-up to get the ink and thoughts flowing. It's the editor's job to find these things, but not in the spirit of scorn or scolding. We are all flawed, and no one can know, without another's eyes on it, if the intent was successfully executed. We work in the privacy of our email exchanges and discussions in the hopes that by the time the piece is published, it is the best it can be. Both positions--writer and editor--feel vulnerable because both are invested in the work of helping the living-breathing-baby-creation-essay-story birth its way into the world. On the editor's side of it, working with writers of all different personalities and experience, I sometimes forget how fragile my own spirit gets when I'm in the writer's chair. And when I'm in the writer's chair, I sometimes forget what an honor it is that someone has spent so much time and thought reviewing my work. Neither chair is easy on the ego. It's hard to look at a work of art or writing -- really, someone's inner world becoming external -- with the mindset that it can very possibly be polished. And yet, this is the art and the craft. To say it not as an adjective/noun, but as a gerund/verb: growing pains. It is a spiritual journey of evolution, one essay at a time. This piece first appeared in Lunch Ticket on February 20, 2015:

http://lunchticket.org/translation-truth-writing-kids/ Things look different from here, on the step/parent side of life. Every day the light shifts and something else is illuminated. Sometimes I write about my kids to understand what shifted, where the shadows now fall on the world, and what the light has revealed of my heart. However, this is not an essay about those light and shadowy things. It is about when the people we love and care for end up in the stories we write. It is an essay about the translation of thoughts to words. It is about the intersection of truth and compassion. Even in our native tongue, everything is an act of translation. Against all odds, we seek to bridge the gap of different life experiences, varied perspectives, divergent opinions, particular regional understandings, distinct cultural affiliations, restricted vocabulary, limited linguilism. Our individual differences are never-ending. It is a wonder we can communicate with each other at all, so we practice the art of translating our inner world into outer expression. We write our thoughts, striving to convey precise meaning. We hope that our intention is successful despite the probability that something will slip through the cracks. There are, after all, so many cracks between the conception of a thought and the delivery of a sentence. We seek to bridge the gap that lies between us, so we sit in a quiet room alone with a laptop or a stack of papers, or on a porch with crows cawing from the neighborhood-laced telephone wires, or in a café with the hissing milk-frother, the droning espresso machine, and the latest Damien Rice playing from the speakers. We mumble to ourselves, group letters and words together, rearrange them, erase, rewrite, start over. We stare into space with glazed eyes, the outlines of everything fuzzy, our ears deaf to the song refrain and the voices that drift through the semi-permeable edges of our thoughts. We are desperate to make sense of things. We must write, because the very act deepens our understanding of the chasms we seek to bridge. We explore and excavate with whatever tool we can find—garden shovel, fingers, cutlery, lover, children, parents—and keep digging through the superficial layers until we hit solid bedrock. Until we hit clarity. Until we find true self-understanding. I’ve been writing for a few years, maybe three, about my kids. They are not twins, but my two girls came into my life at the exact same moment, six years ago, just after the Thanksgiving pie. It was abrupt, joyful, strange, and like most births, painful. They say there’s no way for a first-time parent to prepare; I found this to be true. It is also true that with every birth of something, there is a death of something else. Don’t misunderstand: I love my girls, and I love my life. Still, I need to understand being an adult in this world, and being a parent from a stepmother’s perspective. I need to know myself in the light of that role. Writing illuminates. We parents and stepparents need to read other parents’ and stepparents’ narratives to help us through our own, but I’ve often wondered–do we have the right to write about our kids? Like so many other aspects of kids’ lives, they have little say in what we do, what we write. They are busy trying to make their own sense of the world, and have no voice to give consent to their place in our essays. As adult writers we have insight, but that insight is not necessarily a perspective the kids agree with. Even if they did, the kids do not necessarily want the details of their lives to be exposed to an audience of readers. But our capricious kids do not necessarily NOT want the stories shared either. Earlier this week, writer Andrea Jarrell explored her own thoughts on this topic in her Washington Post essay on writing about kids. In it she asked, “Why do I think my parents are fair game for my work, but I draw the line with my children?” Although Jarrell has chosen not to write about her kids for reasons she states in her essay, her question has led me to the opposite conclusion. Parents and guardians. Every day, with our best judgment, we make a million decisions weighing the kids’ needs and our own. We sign field trip permission slips. Medical authorization forms. Roller rink liability contracts. Oatmeal or Frosted Flakes? Bedtime early or late? Bath on Tuesday or Wednesday? Cell phone or no phone? Playdate or homework? We weigh the kids’ priorities against our own, and approve a Redbox rental of Frozen so we can finish an essay, an hour of games on the iPad so we can figure out ACA health insurance, a bartered cup of frozen yogurt for a quiet afternoon of income tax expense sheets. I write about the kids, but really I write about myself trying to make sense of where I stand now: in the kitchen with my ten-year-old making brownies as a Valentine’s gift for her teacher, or behind the camera taking photos of my fourteen-year-old whose boyfriend just pinned a corsage on her wrist for the Winter Formal, or at the barn next to the girls’ mother because on Sundays the riding lesson is the location for the hand-off that happens every-other-day between households. From this grown-up ground is where I write about my kids. Here, truth and compassion stand side-by-side. Digging for my own truth, my own self-understanding, I want the words I write to be as loving as every decision I make about my girls. There is a Tibetan prayer that I’ve said for years as part of my yoga practice. If I have a guiding light as I translate my inner world into words for others to read, this is it: May I be at peace. May my heart remain open. May I know the beauty of my own true nature. May I be healed. May I be a source of healing in the world. After the essays and stories and books are all written, I hope that my thoughts have been translated precisely. It is a long, long road from one heart to another. There are so many fault lines to cross. I always want my daughters to feel that the stories they’ve been a part of are honest, good, necessary, and loving. This piece first appeared in the literary journal Lunch Ticket on 23 January 2015:

http://lunchticket.org/one-night-strunk-white/ When my fifth-grader returned home Saturday after a week at Outdoor Science School, she brought a twine necklace strung with acorns and colorful beads, an endless stream of facts about the natural world on the mountain, and several riddles she learned from her counselors. Her week at OSS was the first time she’d been away from home, and so when she ran into the house she was overflowing with excitement about her first trip. The cabins (top bunk!); her meals (dessert every day!); the animals (baby frogs and a corn snake!); the owl pellet she dissected (a mouse skull and a shrew bone!). All day, until she was tucked into her bed and finally lulled to sleep by the tap-tap-tap of raindrops against the window pane, the house was filled with her lispy, delighted, never-ending anecdotes. I try to be an involved parent. I try to ask the kids engaging questions, encourage them to dig deeper into the events of their day, reflect back to them what they say so they can hear it for themselves, and then allow them to enhance or revise or elaborate. But on Saturday, juggling good parent practices with my overwhelming stack of spring semester work? Let’s just say that while she happily shared her OSS adventures, I alternated between listening and musing on the phrase “what you resist persists.” Open on the table in front of me lay Strunk and White’s The Elements of Style. I had resisted it since high school. That I have not ever read this slim volume is a bit hard to justify. It takes a day to read, and afterwards not much space on the bookshelf. It’s available for free online in pdf format. Most importantly, though, for an MFA candidate with an affinity toward writing, teaching, and editing, it’s an essential tool that cannot be ignored. Eliminate three out of those four--MFA candidate, writer, teacher, editor--and it is still necessary. When I recently began serving as Blog Editor here at Lunch Ticket, I realized I cannot continue to ride on my grammar and copyediting intuition. I need the vocabulary to explain my editorial suggestions. I need clear reasoning for my choices. I need cold, hard, plain, simple, black and white—Strunk and White--guidance. Dry, right? Elements of Style, though, is not as much about boring rules as it is intelligent advice. All writers of any genre need to craft clear, effective, engaging, bold sentences. Whether novelist, memoirist, or blogger, not having a handle on these tips is a liability. In E.B. White’s introduction, he quotes from Strunk’s principle #17 (omit needless words): Vigorous writing is concise. A sentence should contain no unnecessary words, a paragraph no unnecessary sentences, for the same reason that a drawing should have no unnecessary lines and a machine no unnecessary parts. This requires not that the writer make all sentences short or avoid all detail and treat subjects only in outline, but that every word tell. “That every word tell,” I reread several times. It is a compelling statement. With the drawing and machinery comparisons, it hits home. Unnecessary words and unfocused structure are part of the first-draft process, but a discerning reader can tell a first draft from a polished piece. First drafts hem and haw. They clear their throats and hesitate over ideas. They meander. A discerning reader—an editor, say—may wade through, but a non-discerning reader won’t spend the time traversing rough spots to mine the gems. They will simply move on to another story. Strunk and White’s statement is, in four words, an argument for careful revision. The Elements of Style provides the writer a checklist for that process. The book begins with basic punctuation and grammar rules that any writer should inherently know, followed by a list of composition principles I wish every blogger, essayist, reporter, memoirist, novelist--even Facebook poster, dare I suggest—would consider. Structure of the parts, and of the whole. Clarity of expression. Parallel construction of ideas. Economy of words. Verb tense agreement. While I scratched notes into the margins, my kid bounced off the couch. “Do you like riddles?” she asked, stopping her dance mid-twirl, arms spread out wide. At ten, truly, all the world’s a stage. She is an effervescent joy to our family. She has super powers, has been writing a book since third grade, and has well-timed, absurdist humor. It seems, while she has watched her older sister navigate teenage dramas, she dug her heels into childhood, determined to hang on to simple pleasures until life insists on the inevitable next phase. I can’t say if it’s her jokes or her giggles, but at least once a week we all--even the teenager--end up laughing till we’re in tears. Here’s one of the riddles she brought home from OSS: Q: One night, a king and a queen went into a castle. The next day, three people came out. What happened? A: One knight, a king, and a queen went into a castle. Obviously, the homophone is the key. Night/Knight. Half-listening to her and half-studying Strunk and White led me to consider this riddle from a craft perspective, and I found two other tricks within it that are meant to confound the listener. Sleight of hand is a puzzler’s prized tool, and a riddle’s only goal is to hide an answer in plain sight. When this teaser is spoken aloud, you can almost hear the lack of comma between “a king and a queen”. A serial comma, as I inserted in the answer above, further helps to reveal the three people who emerged from the castle. The most cunning tricks, though, are the most subtle. As I turned this teaser over, a topic covered in Part II of The Elements of Style came to mind. This is a principle Strunk and White call “express coordinate ideas in similar form.” They write: This principle, that of parallel construction, requires that expressions similar in content and function be outwardly similar. The likeness of form enables the reader to recognize more readily the likeness of content and function. Exactly contrary to Strunk and White, this riddle utilizes non-parallel structure to help mask its solution.One k/night is followed by a king and a queen. This use of non-parallel structure is meant to trick the listener. Until now I’d never dissected a riddle. I suppose if you are a riddler, you might consider using non-parallel structure as a tool to disguise the solution. For other writers, however, our goal is not to confound the reader, but to write as clearly as possible. We puzzle in our process so there is no confusion in our final manuscript. We should always strive to give a reader the clearest expression of our thoughts. For parallel structure, we would write one knight, one king, and one queen or a knight, a king, and a queen. Parallel structure. Clarity of expression. Concise writing. As my joyful kid twirled her way through the afternoon, and I made my way through The Elements of Style, I found myself siding with past teachers who once waved their copy of this book to the class. Anne Lamott writes in Bird by Bird, “the only way I can get anything written at all is to write really, really shitty first drafts.” She goes on: You need to start somewhere. Start by getting something--anything--down on paper… [But] the third draft is the dental draft, where you check every tooth, to see if it’s loose or cramped or decayed, or even, God help us, healthy. Another joke from OSS: The present, the past, and the future walk into a bar. It was tense. With all those mixed tenses hanging out together, I am sure it was. Luckily, this and other things are covered in a beautifully quick read: The Elements of Style. What, you don’t have a copy? Get a copy here (or wherever you like to get books), or download a pdf version here. This post originally appeared in the journal Lunch Ticket on December 12, 2014: http://lunchticket.org/stand/

Last night over dinner, after a discussion with our ninth-grader about some challenges she’s grappling with in her personal life, our fifth-grader suddenly asked, “What’s your super power?” I glanced over to her smiling, mischievous face. One of our fifth-grader’s own super powers is the ability to bring levity to difficult moments. She flipped open a sketch book as I thought of our ninth-graders’ worries and wondered if the fifth-grader’s super power will withstand her own impending adolescence. “Here,” she said, clicking her mechanical pencil for more lead. “I’ll tell you the choices.” In shaky cursive she wrote a list. Water, Fire, Magic, Weather, Nature. “Nature means you can talk with animals,” she explained. This is another super power of our fifth-grader. At the barn where she takes riding lessons, she is a veritable Dr. Doolittle. She’s a calming presence among the horses, miniature donkeys, cats, goats, and dogs. There’s even a llama named Ginger who comes when she calls. Our ninth-grader leaned on the table to get a closer look at the list. “I’m fire. Definitely fire.” I exhaled a laugh. Even our ninth-grader chuckled. It’s true, she is fiery. Language has never been a shortcoming for either girl, but our ninth-grader’s eyes easily flash with lightning and her tongue lashes quickly when she senses an attack on her ego or an injustice in her world. Though these girls are not related to me by blood--they are my stepdaughters--I remember being exactly like our ninth-grader in this regard when I was her age. “I’ll tell you the characteristics that go with fire,” the fifth-grader said. In a professorial voice, she cheerfully wrote the words on her sketch pad as she spoke. “Fire: Angry. Destructive. Fighting. EVILLLLL!!!!!” She giggled with mock terror. Our ninth-grader nodded, “Yep. That’s me. Definitely fire.” Her face was neutral, as if this latest trouble had finally doused her fight, and a bit sleepy because it had been a long Monday. “I’m water,” I volunteered. “I can drink enough water to save a city from a flood. I could’ve saved New Orleans from Hurricane Katrina.” I don’t know when I started with the water thing, but it’s been at least since high school that I’ve carried some wherever I go. I only buy purses if they can hold a bottle, and panic a little if there’s no place to refill. “Katrina!” The fifth grader cried with excitement. “That’s her superpower too!” Suddenly I realized what we were talking about. These are the superpowers of the main protagonist and her all-female posse in the book our fifth-grader has been writing and illustrating since third grade. The book was inspired by a game she and her friends used to play at recess. They don’t play it anymore, but recently she informed me that she’s on the second draft of the story. Sitting at the table with the girls, I was suddenly struck by the present moment, and how the three of us held such different awareness of it. The fifth-grader will do almost anything to keep a positive atmosphere. The ninth-grader is invested in protecting her point-of-view. I am mostly interested in doing whatever I can to help these kids navigate their early years so that they grow to be the best version of themselves. As the conversation shifted back to the ninth-grader’s recent challenge, I asked a question here and there, partly to help me understand the events, but mostly to help her clarify them for herself. Right now, of course, it is the end of the world. She struggles because she doesn’t quite know who she is becoming, and has no perspective of the process. At fourteen she’d like all the gates open so she can rush forward, but she has no idea what she’s rushing to. As parents, we try to monitor the gate, regulate the speed, and pull her back in when things are going too far and too fast. The last time I participated in conversations like these, I was the teenager. The beauty of being on the parent side is that time has bestowed perspective. On the cusp of forty I have, at the very least, the wisdom to listen and question, and the experience to consider perspectives other than the limited teenage point-of-view. Lately I’ve been reading essays-in-progress. Some of them are from the Lunch Ticket submission box, others from my colleagues in the MFA program, some from friends who have asked for my feedback. Many of us writers use the page to explore events of our past, and childhood and early adulthood are particularly rich mines. What I’ve noticed as I read through these works-in-progress is that many pieces limit themselves in perspective, despite the wisdom and intelligence of the writer. I imagine that these writers have carried their pain of long-ago events for so many years that they believe the catharsis will come from simply writing their story down. The fact is, we are all the recipient of time’s gift of perspective. Perspective is the power--super power, if you will--of being a writer. As the old saying goes, if you find yourself in a hole, stop digging. While my ninth-grader wallows in her somber thoughts, I, long past those teenage years, can see the hole she’s digging for herself. I can see the holes I dug for myself at that age. As a writer, thinking back to my own childhood events, it is much more healing—and as a reader, light-years more interesting–to go beyond the teenage perspective. As I read these essays-in-progress I sometimes find myself silently begging the author, “What do you, the narrator, think of this now?” Instead of using the pen to only relive childhood events, insert adult insight into those baffling, emotionally-wrought experiences. Let the grown-up wisdom comingle with teenage emotions. As 13th century German theologian Meister Eckhart wrote, “A human being has so many skins inside, covering the depths of the heart… Go into your own ground and learn to know yourself there.” Know what power I wish I had at fourteen? The power to simultaneously hold both the child experience and the adult perspective. Alas, that comes with age. But after living these years, why, when writing our own stories, would any writer eschew this great power? The pen is perhaps the most powerful tool any of us has. How can we communicate or enact change in the world if we cede our own self-understanding? Go ahead, write down those untamed childhood experiences, but lasso them with the perspective of time. When we read your insights, we too transform. Tell me your story of then, from where you stand now. Back East we had storms like "Andrew", "Bertha", "Katrina". Here on the West coast things are a bit less understated. We have the Pineapple Express. It roared into Los Angeles station around ten last night, right on schedule, creaking branches and roofs as it blew, throwing trash cans into the road, putting out traffic lights. I was up half the night huddled under three layers of bedcovers listening to the clanging wind chimes until Darby braved the downpour and took them down. The other half of the night I was awake in antsy anticipation for the first day of the new semester. Here, finally, I am.

Colleagues are trickling into the break room where I again sit blogging. It's a ritual now. I plan my daily arrival for an hour prior to the first seminar and type away. I wonder if this is partly my introverted way of eeking out a bit of non-social time in the morning before diving into twelve-hour clusters of interaction. The idea originated from a self-curiosity. At the start of my first residency last December I was interested to chronicle my MFA experience to see how my mindset changed over the course of the program. Now, on my third residency intensive (with at least another two to go), I wondered if I should bother with the early morning blog session. After all, we sit for such long seminar hours. Even in the rain, perhaps this time would be better spent walking. Or, now that my introverted self has grown accustomed to the faces and rooms, perhaps I could venture into early morning conversation. I wondered this aloud to a colleague as we picked up our registration packets and walked together to the break room. "I don't know. At this point your blogging is a tradition," she said. Ah, the magic word, tradition. Or, in Topol's voice, TRADITION!!!!!! Welp, it's true. So here I am. In the break room. Day 1 of the residency. Welcome back, Antioch. Today's schedule: Writing about illness Researching the 3rd semester academic paper Genre writing workshop (CNF) Evening graduating student readings This piece originally appeared in the online journal Lunch Ticket on September 12, 2014: http://lunchticket.org/courage-it-takes/ Sitting under a café umbrella recently, sipping iced tea with an MFA colleague, the conversation naturally, unsurprisingly, turned to writing. We’re both in our second semester of graduate school. As I’ve mentioned previously in this blog, I’m “Creative Nonfiction.” It’s a fact which never ceases to amuse my fiancé who takes it as an existential statement. My tea-sipping friend is “Fiction,” which amuses my fiancé even more.

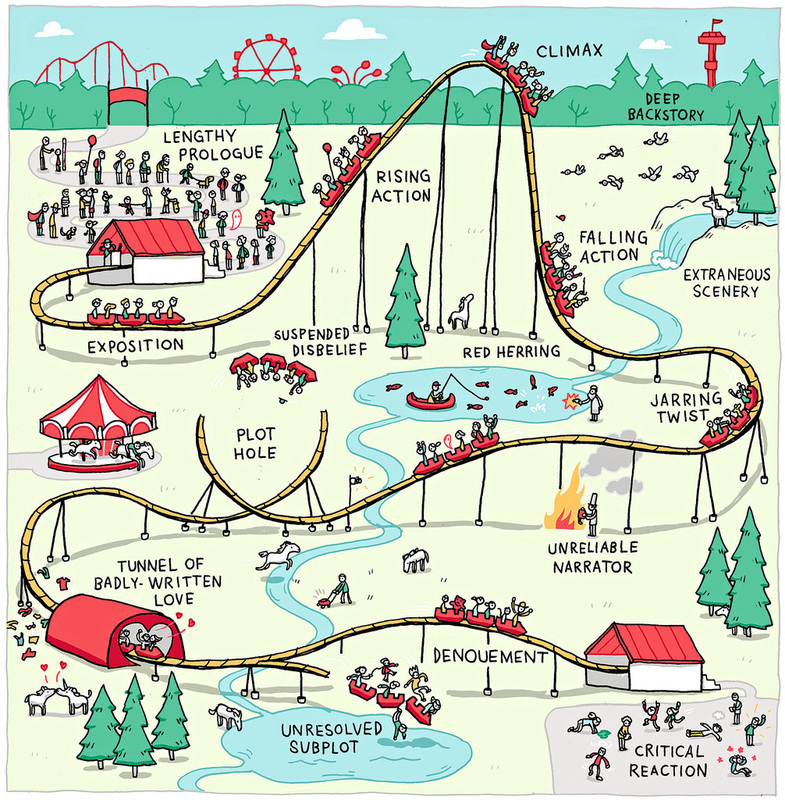

Regardless of fictive or nonfictive embodiment, my friend and I both agree that the monthly packets we are required to submit to our MFA mentors are very real. Troublingly so. My most recent packet of twenty creative writing pages and two book annotations was due to my mentor in mid-August. For two days afterwards I celebrated its completion by not writing a single word (status updates and margin notes inBehind the Beautiful Forevers, of course, aside). On the third day I intended to get back to writing, but—nearly a week earlier than expected—I received my mentor’s return email: a detailed letter, in-line track change comments, and lecture notes on a particular topic she suggested I study. I was paralyzed for a full week afterward. Could. Not. Write. Anything. I sat with my friend at the outdoor café during that time. It was one of those blazing hot Saturday afternoons when everything melts: ice in our drinks, lipstick in my purse, ego. We sat together, pulling our sweat-soaked shirts away from our backs, fanning cigarette smoke from the table next to ours. Inside the café, the A.C. was on full blast but the room was crowded with chatter, and she and I both had some things to get off our chests. She, too, had a hard time getting back to work after sending off her last packet. “I’m afraid of criticism,” she said. It was powerful to hear her express what I had been feeling. Of course criticism—particularly at the hands of a knowledgeable and supportive mentor—is meant to be helpful. Indeed, it’s a primary element of why we both came to this program: to receive critical feedback about our work. But the fear we associate with criticism is attached, I think, to shame. Shame that the basket we’ve put our eggs in is full of holes. Shame that we will fail. Shame that there is a right and wrong to writing and that, ultimately, it is just beyond our personal abilities to get it right. Fear that we are not capable of stepping into our highest creative self. My friend’s reflection of my own fears was enough to remind me of a time, years ago, when I had not allowed my fears to stop me. After years of studying classical music, sometime in college I ended up with an acoustic guitar and a book of folk songs. Joni Mitchell, Pete Seeger, etc. I had been raised on these songs by a guitar-strumming dad. My first concerts were folk festivals where my parents spread a blanket and we picnicked on my mom’s cold fried chicken and berry pies. The folk songs in the book hit a deeply personal spot from my earliest childhood memories. It was a place that classical music, as much as I loved it, had never tapped. The book was a doorway, and when I walked through it, I walked away from classical music, stepped onto a path of songs, and, shortly, started writing my own. Right away came the desire to sing for others. A moment later, my stomach clenched with fright. Stage fright, like fear of criticism, can be debilitating. It can also be exhilarating. I’m not a fan of roller coasters, but I wonder if the draw to them is similar. Do coaster-lovers shake in fear? Do they wonder if they can handle it? Do they get a rush from the courage it takes to ride? This is what it feels like, for me, when I send in my mentor packets. I silently beg, as I hit send, that my mentor’s feedback will be enough to kindly push my edge, an edge just shy of disablement. Often, to work out fears that arise in my new(ish) writing endeavors, I look back to my life in music. How did I overcome my life-long stage fright so that I could pursue my love of singing and songwriting? I showed up. Back then, I was up against all these same fears of failure and shame, but my desire to get better at my craft was larger than my fears. I knew the only way to improve was to do it. Perform. As much as possible. The solution? I joined the busking world. I didn’t have to wait for a club booker to let me in the door. I could pull up a piece of sidewalk and play every night, which I did throughout summer and fall until my fingers froze, and then again the following spring. There was a good community in my Boston busking world days—Amanda Palmer, Guster, Mary Lou Lord, and many others who passed through for a week or for years—but also, I learned to stand up in front of an audience. I learned to show up against my fears. After a few hours at the café, our iced teas were finished, our conversation spent, our backs sweaty. I drove my friend several blocks to where she had parked. “I made something for you,” she said as she unlocked her car. From the backseat she pulled out a pale green cotton bag with two wide shoulder straps and a red and white swath of cloth down the center. I can’t sew at all, but I appreciate the craft. Her stitches were perfect. The muted colors were imbued with my friend’s gentle spirit. The kindness was almost overwhelming. Fingering the stitches of my friend’s gift, I remembered something an old teacher used to say: How you do one thing is how you do everything. I haven’t read my friend’s writing, not yet. Nor has she yet read mine. But I am certain that when the day comes for us to exchange not just our trepidations but our art, we will find in each other’s writing the level of courage, commitment, and care that we bring to our other arts and crafts. As with everything, sometimes fear stops us for a few days or a week. But always, every time, our desire to do this—to explore questions, share stories, to write—leads us through the turnstile and back onto the ride. |

Archives

May 2019

Categories

All

|