The new Winter/Spring 2017 issue of Lunch Ticket came out a few days ago, and the next day I stepped down from my post as editor-in-chief and passed the baton to my successor. Still, after months of working on pulling together this issue, I'm not ready to walk away. There're so many fantastic interviews, poems, essays, translations, short stories... Start here with my Word from the Editor and then pop over to the magazine: I began drafting this essay at the end of the presidential election season, in light of what many of us thought would be a landmark historical moment: the United States’ election of our first woman president. On November 8, as we are all too aware, despite winning the popular vote by (as of this writing) over two million, the Electoral College results tallied in favor of her opponent. Spurred by a campaign rhetoric that relied on a cornerstone of violence, fear, and hatred, the president-elect continues to provoke considerable domestic and international criticism. Shocked by what this outcome revealed—that nearly half of voters responded positively to his rhetoric—, many say that it appears we have two Americas, red and blue. Like warring tribes, we’ve now turned away from each other and returned to our camps, separated by a modern Mason-Dixon line in the divided states of America. We curl up with our own news sources, revel in our own truths. The fissure is too deep, we say, and so draw a line that relieves us of reconciling our differences, scrutinizing root causes, or compromising our values. Fissure is just one analogy to describe the state of the (dis)union. We could, instead, look at our picture of this country and say that part of our view was obscured. As political theorist Andrew Robinson writes, “Any particular way of seeing illuminates some aspects of an object and obscures others.” With our sights set on equality, community, and eco-conservatism, we now realize that we missed a large segment of the picture. Feminist scholar Julie Jung calls this synecdochic understanding: using part of something to represent the whole. As it turns out, many of us—including every major newspaper and pollster—were looking at the U.S. through this device. The election results lifted the shroud. Now we’re squirming in discomfort about two new sources of awareness: that which was underneath the shroud and the shroud itself. As long as there’s a shroud, the former cannot be helped. But we should question why we didn’t investigate our blind spots, why we overlooked the shroud. Often writers think of revision as a task grudgingly—or happily—undertaken to perfect our work. We reread our words seeking moments of disconnect for the bits that don’t seem to belong, and we assess their worthiness to the story. We want our work to make sense, so we seek a narrative arc. If something doesn’t propel the narrative or make consistent sense for a character, it falls to the cutting room floor. Smooth out the wrinkles, wash out the stains, turn in the essay, get an A. But what if we revised revision? What if instead of smoothing out the wrinkles, we held them to a magnifying glass? In this approach, so-called flaws would not to be brushed away but, rather, probed. As writers, artists, and activists, can we approach our work so that revising—that process of looking closely at our work for moments of disconnect—is not a process of glossing over but of examining more closely? Instead of manipulating truth in service of a smooth narrative, we should examine our motives for creating a smooth narrative to begin with. In this light, revision becomes not an act of making something flawless but, rather, making it more whole. As Annie Dillard writes in Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, “Go up into the gaps. If you can find them; they shift and vanish too. Stalk the gaps. . . This is how you spend this afternoon, and tomorrow morning, and tomorrow afternoon.” Given this approach to revision, what cultural material have we rushed to brush away before truly exploring? In our attempts to move toward equality and understanding, it’s now apparent that we’ve not fully attended to the underlying bigotry, misogyny, and xenophobic ills that this election season oozed to the surface. We have a country half-peopled by those who either resonate with or can overlook narratives of distrust and resentment for “the other.” Although it feels for many that we’ve now taken six decades’ worth of steps back, perhaps the reason we need to do so is because our progressive vision glossed over too many foundational cracks. While we were moving forward, half the country planned a revolt. If we’re committed to walking our talk of inclusion, then we need to hunker down in this new climate to revise our understanding of the United States and build something more tenable. It was with these thoughts that I have been turning the pages of our tenth issue, which is my last as editor. It appears to me that what we’ve put together here is a multi-layered, multi-genre conversation about gaps in cultural narratives, moments of disconnect or desire for connection, and an attempt to, as Dillard wrote, stalk the gaps. If anything, the eighty-two pieces in this Winter/Spring 2017 issue, from interviews to art to new and translated work in fiction, poetry, and nonfiction, point to the value and necessity of open discourse, of reading the white space between words along with the words themselves. In her interview for our Lunch Special, Maggie Nelson says “every draft is slathered with self-deceptions,” which we must examine in order to get to honesty. In a separate interview, artist Harry Dodge responds to Nelson’s The Argonauts by reminding us that “any piece of art, whether nonfiction or otherwise, is a construction” and asks “whether language is able to do the work of describing fluidity, or anything really.” In his interview, poet Fred Moten talks about how writing should not suppress what he calls the monstrous, the strange, the radically disruptive fundamental aspects of life. And Susan Southard says of Nagasaki, a braided nonfiction narrative about the U.S. bombing in WWII, “I felt it was so important to bring [the survivors], still hidden from view in our country, into visibility.” This theme of visibility is stitched throughout the issue. We could say the stitches are like sutures, repairing cultural wounds, but the stitches are also like hand-sewn needlepoint, each threaded with its own palette, in its own frame, its own unique picture. Gabo Prize winner Jim Pascual Agustin’s poem Danica Mae is about the recent mass killings in The Philippines. Diana Woods Memorial Prize winner Sarah Pape’s CNF piece Eternal Father & The Other Army brings to light a nuanced experience of depression. Call to Arms, Marine Lieutenant Lisbeth Prifogle’s featured essay, is about the need for publishing “stories that could alleviate the fear, isolation, depression, and anxiety of joining the old world after a deployment.” Grace Lynne’s featured art collection, The Exploration Series, seeks to show “Black culture in a new light, and open people up to a side of my culture that they haven’t seen.” I could, without reservation, list every single one of the eighty-two pieces in this issue. It is a beautiful, heartbreaking, mind-expanding collection, and an honor to publish this one as my last. After three issues as editor, this is a bittersweet goodbye as I now step away from the journal. My studies in the Antioch MFA program and, recently, as a Post-MFA in Pedagogy student are nearly complete, and Lunch Ticket has and always will be student-run. My work leading the editorial and production staff, reading our submissions, developing relationships with our writers and artists, and connecting with literary and art lovers who come to our pages has been humbling, inspiring, and invaluable for my personal growth as a writer and as a woman in this world. Thank you for being here, for sharing your stories, for reading ours. And take good care, Arielle Silver Editor-in-chief, Lunch Ticket

0 Comments

I ran off to Big Sur last week, and when I got home, this was waiting on the doorstep. I want to write a whole story about it - it's an MFA in Creative Writing, after all, and after 3 years' journey through my primary study in creative nonfiction and secondary in fiction and literary translation, I should be able to string together some delightful narrative. But, truth is, while I've earned the degree, I'm still in the story. This semester I'm concurrently enrolled in a Post-MFA Certificate in Creative Writing Pedagogy and a Professional Development Semester in online CW course development. And as long as this is CNF, let's be honest: I won't be done with my PMFA Certificate till June. Also, I'm still serving as editor-in-chief of Lunch Ticket (and completely honored to do so), and still deeply entrenched in grad school.

But I want to sit still long enough to look at this degree in my hands, because I've worked my booty off these past almost 3 years. I've grown tremendously as a writer, editor, and teacher. I've written and rewritten a book-length manuscript four times, started work on a historical novel, studied French and translated a book and a half and some poetry into English, really studied the art and considerations of translation, have researched and written (and published) about the wicked stepmother trope, learned a great deal about the literary world and publishing an online journal, and have published a bit of my own work. I'm still fired up, and all of this is due to my incredible mentors and the support of the whole AULA MFA community. Never ending gratitude for the guidance and influence of these writers and teachers: Brad Kessler (Birds in Fall, Goat Song) Hope Edelman (The Possibility of Everything, Motherless Daughters) Dan Bellm (Practice, Description of a Flash of Cobalt Blue) Peter Selgin (The Inventors, Confessions of a Left-Handed Man) Peter Nichols (The Rocks, A Voyage for Madmen) Bernadette Murphy (who gets all the credit for getting me to apply to this program) (Harley and Me, Zen and the Art of Knitting) Sharman Russell (Diary of a Citizen Scientist, Teresa of the New World) Christine Hale (A Piece of Sky, A Grain of Sand) Jenny Factor (Unraveling at the Name) Audrey Mandelbaum and MFA program director, Steve Heller (The Automotive History of Lucky Kellerman), who for some reason continues to trust me with the keys to Lunch Ticket, And, lastly but most importantly, my dear husband Darby Orr, who served as my first editor, married me in the middle of this whole mess, and who has encouraged me every word along the way. "Trust in the synergy of the things that are coming together, and don't fret about the rest." – Amy Sage Webb My AULA creative writing pedagogy mentor, Amy Sage Webb, said the above last December in an exciting seminar I attended during that particular MFA residency. They say when the student is ready, the teacher appears; in that moment, I knew I would enroll in the Post-MFA Program in Creative Writing Pedagogy just to have the opportunity to study with Amy, who is also Co-Director of Creative Writing at Emporia State University in Kansas. What I didn't realize at the time was that it was a two-for-one deal with co-mentor, Tammy Lechner, a teacher and Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist - talk about synergy. Since mid-June, with Amy and Tammy and my small Post-MFA cohort comprised of six other writer-teachers, I've been in constant discussion about what makes a great teacher, what the best college teachers do to create engaging and stimulating learning environments, and how to bring these macro-ideas into the composition and creative writing classroom. We've discussing questions about authority, gender issues, learning theory, teaching philosophies, how to evaluate creative work, what higher education politics mean to our budding careers in academia, and how to develop learning objectives that foster discipline-related intellectual growth alongside personal growth in our students. Concurrently, I opted in for a double-wammy of enrolling in a Post-MFA Professional Development semester focused on book coaching and online creative writing pedagogy. With author and teacher Kate Maruyama, and writer and pedagogy specialist, Curt Duffy, alongside guidance from Amy and Tammy, I've been developing a community online writing course to teach later this autumn. The course idea comes from something I've been fired up about lately: weird writing structures, a/k/a lyric essay, a/k/a where poetry and prose meet. The course is meant to inspire first drafts of new work for seasoned and new writers alike, and will explore non-traditional forms to find inspiration from the mundane moments of every day. Since the course will be in feast-centered November, with my lifelong interest in cooking and food I couldn't resist adding a little twist. The course is called "Feasting on Form: Noodling Around with Experimental Creative Nonfiction." That whole month (the course is 4 weeks), we'll explore bite-sized ideas taken from grocery lists to lonely snacks to shared meals -- all ripe for narrative discovery -- and share brief essays that we write inspired by these moments. I believe some students will leave the class with solid drafts close to submission-ready for literary journals. I’ve frequently thought of Amy's words about synergy since receiving my MFA degree in June. As I query literary agents for my memoir, continue to lead the editorial team on Lunch Ticket, work through my Post-MFA courses, occasionally squeak out a new essay or a few words in my novel-in-progress, and plan the yoga and creativity retreat in January, I could wonder if my head-down work ethic blinds me to the viability of making a professional career of writing and teaching. After all, one agent who recently turned me down wrote, “I really like your writing—I really do!... but, I’ll be honest with you, I’ve had the shittiest time placing memoir lately.” But after repeating the synergy mantra since December, it comes unbidden now, and I truly believe it. I’m not fretting very much. I trust in the synergy of the things that are coming together – the retreat! My studies! My writing! It all feels too good to fret about. And in any case, I’m having fun. The other night, my writing group gathered for our twice-monthly meeting at my house. We've been meeting together for more than a year. Lately, my increased pedagogy coursework leaves little time for creative writing, so I depend on these friends to keep me accountable to my artistic side. This week I only had three pages of new work for them to read, but they were three pages I wouldn't have written otherwise. Inspired by my group’s feedback, I’ve already redrafted the piece and shipped it off to a literary contest. Before we settled into the meeting, one writer in the group confessed to me about feeling concerned about her future job prospects. She's about ten years younger but we've shared some similar life paths through music, writing, communal living, and honest day jobs. She asked me about the coursework I've been doing. Will it guarantee a job, she wanted to know. How can I answer that, after my strange career life: a touring musician, a chef, a photographer, an artist model, a newsstand clerk, an administrative assistant, a yoga teacher, a production supervisor at a music label? How do you answer a question like that in today's gig economy in which universities depend on adjunct faculty the same way for-profit companies avoid benefit payouts with outsourced consultants? But Amy Sage Webb’s words come back to me. I need to remember to share them with my writing group. “Trust," Amy says. By its nature, trust is about the unknowable, the uncertain. Trust is about things just out of sight, just beyond the bend, though not as far away as, perhaps, faith. Trust reminds me of the E.L. Doctorow quote, "Writing is like driving at night in the fog. You can only see as far as your headlights, but you can make the whole trip that way." When I’m stuck midway through a chapter of my novel and start fretting about where it might be heading, I think back to this quote. But it helps me even more when I lift my head from my school work. “Trust in the synergy of the things that are coming together.” The road is beneath the tires, I can see as far as November to the month-long writing course, and as far as January to the yoga and creativity retreat. Ten years ago, I didn’t have this kind of trust that things will work out fine, but perhaps, more than anything, that’s what the decade has taught me. This time next year? I have no idea. But I’m not fretting. Where we put our attention is how we define our reality. And like I said, I’m having fun. These past five months I've been honored to serve on a literary journal - Lunch Ticket - as Blog Editor. This week, in particular, I am reflecting on how special the writer/editor relationship is, how much I've learned in this role, and how appreciative I am that my writers have been so willing to work with me (and each other) in this way. It is beautiful and humbling work.

All artists know the ego-challenge of handing their creation to someone who intends to review it with a critical eye. An editor searches for missing commas, redundant phrases, and awkward wording, but they're also reading closely to be sure all the sentences *belong*. Sometimes the opening line doesn't grab. Sometimes the last line is lukewarm. No matter how much time a writer has spent crafting it, sometimes an entire paragraph is simply in the wrong essay, the first page just a throat-clearing, a warm-up to get the ink and thoughts flowing. It's the editor's job to find these things, but not in the spirit of scorn or scolding. We are all flawed, and no one can know, without another's eyes on it, if the intent was successfully executed. We work in the privacy of our email exchanges and discussions in the hopes that by the time the piece is published, it is the best it can be. Both positions--writer and editor--feel vulnerable because both are invested in the work of helping the living-breathing-baby-creation-essay-story birth its way into the world. On the editor's side of it, working with writers of all different personalities and experience, I sometimes forget how fragile my own spirit gets when I'm in the writer's chair. And when I'm in the writer's chair, I sometimes forget what an honor it is that someone has spent so much time and thought reviewing my work. Neither chair is easy on the ego. It's hard to look at a work of art or writing -- really, someone's inner world becoming external -- with the mindset that it can very possibly be polished. And yet, this is the art and the craft. To say it not as an adjective/noun, but as a gerund/verb: growing pains. It is a spiritual journey of evolution, one essay at a time. Back East we had storms like "Andrew", "Bertha", "Katrina". Here on the West coast things are a bit less understated. We have the Pineapple Express. It roared into Los Angeles station around ten last night, right on schedule, creaking branches and roofs as it blew, throwing trash cans into the road, putting out traffic lights. I was up half the night huddled under three layers of bedcovers listening to the clanging wind chimes until Darby braved the downpour and took them down. The other half of the night I was awake in antsy anticipation for the first day of the new semester. Here, finally, I am.

Colleagues are trickling into the break room where I again sit blogging. It's a ritual now. I plan my daily arrival for an hour prior to the first seminar and type away. I wonder if this is partly my introverted way of eeking out a bit of non-social time in the morning before diving into twelve-hour clusters of interaction. The idea originated from a self-curiosity. At the start of my first residency last December I was interested to chronicle my MFA experience to see how my mindset changed over the course of the program. Now, on my third residency intensive (with at least another two to go), I wondered if I should bother with the early morning blog session. After all, we sit for such long seminar hours. Even in the rain, perhaps this time would be better spent walking. Or, now that my introverted self has grown accustomed to the faces and rooms, perhaps I could venture into early morning conversation. I wondered this aloud to a colleague as we picked up our registration packets and walked together to the break room. "I don't know. At this point your blogging is a tradition," she said. Ah, the magic word, tradition. Or, in Topol's voice, TRADITION!!!!!! Welp, it's true. So here I am. In the break room. Day 1 of the residency. Welcome back, Antioch. Today's schedule: Writing about illness Researching the 3rd semester academic paper Genre writing workshop (CNF) Evening graduating student readings This piece originally appeared in the online journal Lunch Ticket on September 12, 2014: http://lunchticket.org/courage-it-takes/ Sitting under a café umbrella recently, sipping iced tea with an MFA colleague, the conversation naturally, unsurprisingly, turned to writing. We’re both in our second semester of graduate school. As I’ve mentioned previously in this blog, I’m “Creative Nonfiction.” It’s a fact which never ceases to amuse my fiancé who takes it as an existential statement. My tea-sipping friend is “Fiction,” which amuses my fiancé even more.

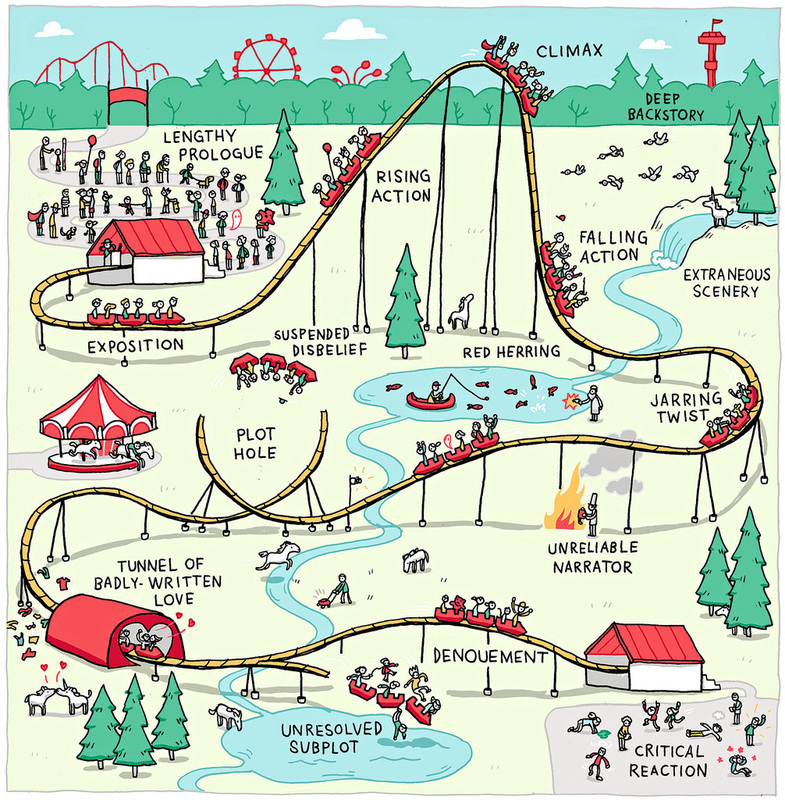

Regardless of fictive or nonfictive embodiment, my friend and I both agree that the monthly packets we are required to submit to our MFA mentors are very real. Troublingly so. My most recent packet of twenty creative writing pages and two book annotations was due to my mentor in mid-August. For two days afterwards I celebrated its completion by not writing a single word (status updates and margin notes inBehind the Beautiful Forevers, of course, aside). On the third day I intended to get back to writing, but—nearly a week earlier than expected—I received my mentor’s return email: a detailed letter, in-line track change comments, and lecture notes on a particular topic she suggested I study. I was paralyzed for a full week afterward. Could. Not. Write. Anything. I sat with my friend at the outdoor café during that time. It was one of those blazing hot Saturday afternoons when everything melts: ice in our drinks, lipstick in my purse, ego. We sat together, pulling our sweat-soaked shirts away from our backs, fanning cigarette smoke from the table next to ours. Inside the café, the A.C. was on full blast but the room was crowded with chatter, and she and I both had some things to get off our chests. She, too, had a hard time getting back to work after sending off her last packet. “I’m afraid of criticism,” she said. It was powerful to hear her express what I had been feeling. Of course criticism—particularly at the hands of a knowledgeable and supportive mentor—is meant to be helpful. Indeed, it’s a primary element of why we both came to this program: to receive critical feedback about our work. But the fear we associate with criticism is attached, I think, to shame. Shame that the basket we’ve put our eggs in is full of holes. Shame that we will fail. Shame that there is a right and wrong to writing and that, ultimately, it is just beyond our personal abilities to get it right. Fear that we are not capable of stepping into our highest creative self. My friend’s reflection of my own fears was enough to remind me of a time, years ago, when I had not allowed my fears to stop me. After years of studying classical music, sometime in college I ended up with an acoustic guitar and a book of folk songs. Joni Mitchell, Pete Seeger, etc. I had been raised on these songs by a guitar-strumming dad. My first concerts were folk festivals where my parents spread a blanket and we picnicked on my mom’s cold fried chicken and berry pies. The folk songs in the book hit a deeply personal spot from my earliest childhood memories. It was a place that classical music, as much as I loved it, had never tapped. The book was a doorway, and when I walked through it, I walked away from classical music, stepped onto a path of songs, and, shortly, started writing my own. Right away came the desire to sing for others. A moment later, my stomach clenched with fright. Stage fright, like fear of criticism, can be debilitating. It can also be exhilarating. I’m not a fan of roller coasters, but I wonder if the draw to them is similar. Do coaster-lovers shake in fear? Do they wonder if they can handle it? Do they get a rush from the courage it takes to ride? This is what it feels like, for me, when I send in my mentor packets. I silently beg, as I hit send, that my mentor’s feedback will be enough to kindly push my edge, an edge just shy of disablement. Often, to work out fears that arise in my new(ish) writing endeavors, I look back to my life in music. How did I overcome my life-long stage fright so that I could pursue my love of singing and songwriting? I showed up. Back then, I was up against all these same fears of failure and shame, but my desire to get better at my craft was larger than my fears. I knew the only way to improve was to do it. Perform. As much as possible. The solution? I joined the busking world. I didn’t have to wait for a club booker to let me in the door. I could pull up a piece of sidewalk and play every night, which I did throughout summer and fall until my fingers froze, and then again the following spring. There was a good community in my Boston busking world days—Amanda Palmer, Guster, Mary Lou Lord, and many others who passed through for a week or for years—but also, I learned to stand up in front of an audience. I learned to show up against my fears. After a few hours at the café, our iced teas were finished, our conversation spent, our backs sweaty. I drove my friend several blocks to where she had parked. “I made something for you,” she said as she unlocked her car. From the backseat she pulled out a pale green cotton bag with two wide shoulder straps and a red and white swath of cloth down the center. I can’t sew at all, but I appreciate the craft. Her stitches were perfect. The muted colors were imbued with my friend’s gentle spirit. The kindness was almost overwhelming. Fingering the stitches of my friend’s gift, I remembered something an old teacher used to say: How you do one thing is how you do everything. I haven’t read my friend’s writing, not yet. Nor has she yet read mine. But I am certain that when the day comes for us to exchange not just our trepidations but our art, we will find in each other’s writing the level of courage, commitment, and care that we bring to our other arts and crafts. As with everything, sometimes fear stops us for a few days or a week. But always, every time, our desire to do this—to explore questions, share stories, to write—leads us through the turnstile and back onto the ride. This post appeared in the online journal Lunch Ticket on June 27, 2014:

http://lunchticket.org/mfa-myths-artist/ They say cardio is the first to go, which I suppose explains last evening's huffing and puffing through my first run since the day before residency began. Normally I'm a runner - around 25 miles a week - but last night it was hard to tell. Each step on the asphalt was foreign. My lungs were weak. Despite what the passing cars may have seen, I was the Stay Puft Marshmallow man. The first time I heard "M.F.A.; My Fat Ass" was at a closing event at the end of last term where the graduating students spoke a few words reflecting on their journey through the program and, particularly, how they fared in the final semester. A fiction writer with a lighthearted countenance and an admittedly soft middle offered the above definition of the degree he would be awarded the following day. His cohorts chuckled in agreement. That's all I remember about him, but it struck a chord, and I made a silent note-to-self. We writers do, after all, sit a lot. But just like writing, exercise has been a savior for me. We could get into self-image and how women are depicted in the mass media, we could even get into childhood issues--blah blah blah--but the fact is, what's done is done. I am a woman in this culture, with this upbringing, with this mind chatter. The antidote has been physical activity. Running, yoga, cycling, hiking -- whatever it is, the mind chatter changes from This body is not good enough to Damn, I am grateful for this body. Physical movement quiets my mind chatter. Every time I hear "M.F.A. = My Fat Ass", I cringe. Admittedly, during the 10-day residency our schedules are tight. A single day at residency looks like this: hour commute, followed by an hour blogging, two in seminar, a (seated) lunch, another seminar, a workshop, perhaps dinner, and a two hour evening reading with four graduating student writers and one featured guest writer. Then the commute back home. Nine days of it. Thirty miles driving. My body moved barely an inch. I’m not whining though – the residency rocks – but what about the other five months of Project Period? For me at least, at times of my life when I’ve been particularly sedentary, it’s more of outlook than schedule. There are a ton of myths about being an artist. And just like the media's image of women, I have at times bought into those wonky narratives. Hook, line, sinker. * * * Myth #1: Poor artists. Ten years ago I was in another graduate program. (Some people buy cars; I collect almae matres.) Berklee College of Music gave me some scholarship money; I packed my bags. Instead of finding $75 for a soft-shell guitar bag, I bolted industrial-strength straps made to move pianos onto my hard-shell case and carried the weight on my back like a tortoise. Instead of picking up a long, warm coat for the Boston winter, I shivered in my leather motorcycle jacket, which was just long enough to assist the freezing rain in sliding down my back and soaking my jeans from belt to boots. I was broke. Adamantly broke. Myth #2: Starving artists. At Berklee, dinner was usually rice and beans; breakfast was rice pudding from the leftovers. My roommate and I split $200 for food each month. The mono-nutrient diet upset my belly and my energy was low but when I caught my roommate spending $2 for a slice of pizza between classes -- 1% of our food budget for the month on one meal -- I nearly slid into a rage. I stomped home and sulked over another Tabasco-doused rice bowl. Myth #3: You need to suffer for your art. I walked two miles to Berklee each day, through the snow, uphill both ways, barefoot. Okay, it’s a bit hyperbolic, but you get the gist. Each day my shoulders were burdened with instruments like my body was a pack mule. Every day that damn guitar case tried to kill me. Myth #4: Talent is innate and "making it" is a concept only available to a privileged few. All my classmates were rockstars or the offspring of rockstars. Talented. Beautiful. On their way to successful careers doing exactly what they were born to do. I, on the other hand, was a folk-singing daughter from a very normal family. I wasn't a prodigy, nor were my parents. My pedigree, I believed, would be my ultimate handicap. Not surprisingly, despite graduating with honors, then signing, recording, and touring, the way I burned out was less like a Bacchanalian feast of cocaine and backstage groupies, and more like a balloon flying through the air, coming untied, and simply dropping to the ground, useless, spent. It took me years to realize I had done it to myself: I had bought the myths. * * * Things are winding down here in low-residencyland. Those of us not graduating have already disappeared into an online world called Project Period. During the next five months we will strain to stay connected through Sunday check-ins, monthly reading conferences, Facebook groups, occasional coffee dates for the locals, and, most celebrated, through online magazines and literary journals where, hopefully, we'll see our colleagues' bylines. Writing is a solitary activity, but the residency stokes a warm campfire. The re-entry back to day jobs and family life is welcomed, but strange. Mostly, it is a welcome return to normalcy. I’m looking forward to reconnecting with my family, catching up on sleep, eating a simple meal at home. Basically, finding balance between mind, body, and spirit. And at the top of my to-do list is exercise. Over the past eight days, my thighs have become a wee bit bigger. My belly is somewhat more rotund. And oh, my hips, my hips, my hips. Thankfully, the mind chatter hasn’t started, but I’m not going to wait for it. I don’t buy into the artists myths anymore. It’s possible to live the creative life as an artist and the balanced life of a healthy human. Even as we make time to write, eat, sleep, we must make time to care for our physical bodies. They carry us through this creative life. They are the only true vehicle we’ll ever have. Family, home, paychecks. Heartbeat, breath, sweat. Body, mind, spirit. Out beyond ideas of wrongdoing and rightdoing,

there is a field. I'll meet you there. Jelaluddin Rumi - 13th century Middle school is full of toxic pre-teens. I know most of them are ultimately good people trying to work out their confused pre-teen crap, but it can be painful. You'd think that by graduate school toxic personalities would have softened, or at least melted into a puddle of nothing worthwhile, left by the dump behind the cafeteria. You'd think those personalities certainly wouldn't find their way into a program, at least not one like a Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing. You'd think that life would have thrown them enough curveballs to show them that a pattern of burning bridges, of writing publicly about petty personality judgments, of attempting to skewer the very community -- the MFA program, the greater literary community , etc -- that is in place to bolster us all up will not come to any good. You'd think. My oldest stepdaughter finished middle school a few weeks ago. I dare say, if she didn't finally learn quadratic equations, didn't run the P.E. mile in under 9 minutes, didn't memorize how to build a major triad or find the relative minor, I hope she learned how to walk away from drama llamas. Looking back on my own middle school years, I can hardly recall my own experiences with this. I had forgotten, I suppose, how cruel kids can be. No doubt my super bright, super cool, super gorgeous middle schooler was only attacked out of jealousy. Hell, if I were a middle schooler with her, she's the girl I'd want to be. But still, at thirteen how can she have this perspective? Even with her graceful confidence, how can she know, truly, how awesome she is? She's got thirteen years of life on this planet, eight years of school under her belt. Over the past three years, whenever she came home burning in the shame of careless words, stewing in anger at the latest antics of the mean girls, teary about shifting social groups, we tried to remind her that the only one who can truly assassinate her character is herself. We taught her to know her center, to know herself, to not worry about the negative energy others might try to pull her into. We tried to help her temper her fire, rise above, stand in the beauty of her own true nature. As her father says, Take the high road. There's less traffic up there anyway. And yet, there are some who manage to squeeze past the middle school graduation stage, manage to squeak through high school, college, perhaps employment. Perhaps they land, with a particularly wicked pen, in an MFA program in creative writing. There are some who carry their toxicity with them through their life, and I imagine that these particular people must find some benefit along the way. Perhaps they are of the camp that any attention -- even negative -- is good. Perhaps they think that they are honing their craft by dwelling on dark emotions. Perhaps they think that there is a place for them in this world. And perhaps, standing with colleagues at an MFA gathering, drinks in hand, schmoozing among their classmates, they believe that their fellow writers are unaware of their online blog posts. Perhaps they believe their classmates do not mind, or that they might even applaud the way they suck camaraderie out of a room. Maybe they believe there is a volley that can ensue: they throw toxic waste from their blog, and the writer who has been lambasted then throws toxic waste from their blog, back and forth like a tennis match. Perhaps they believe this is a way to make friends. And yet they are wrong. They are wrong because we have all been to middle school, and all of us (except this type) have learned that toxic waste dumps are no place to hang out. We all (except, of course, the drama llamas) choose to spend our lives being inspired, building community, focused on our work, finding writers who we admire, and reading their work. We choose to be the bolsters, because we trust the process and know that when we lift up others, others lift up us. We choose the high road, above the muck of people who prefer to wallow in waste. We find that despite the fact we are all on this road – the high road--, it does not feel crowded. There’s spaciousness. The path is clear because we are moving forward, helping each other along the way. And truly, the view from up here, at times, can simply take your breath away. I feel human again, a state I much prefer to the walking zombie version of myself that I've embodied the past two days. Sadly, though, to refind myself I had to miss last night's readings. These nightly events are a highlight of the residency, a time to listen to my colleagues' and some faculty work and match names with faces, but my Monday meltdown had run into Tuesday and classmates were beginning to ask if I was feeling sick. I wasn't, but I desperately needed rest. Ten hours in my darkened bedroom of sleeping/waking/sleeping seems to have been just the medication I needed. Today: bright eyed, bushy tailed, so to speak.

Despite my exhaustion, though, my mind has been clear. Like last term, my experience this time is that I am becoming a better writer by just being here at the residency. (Whether that is reflected in these rushed early morning posts is another story.) Even in seminars more geared to other genres -- Monday I sat in on Janet Fitch's seminar about dialog in fiction -- I am absolutely deepening my understanding of things I already do well and/or issues that come up in my writing that have not felt authentic. Authenticity, it seems, is perhaps the number one key to good writing. Yesterday, however, was less about craft and more about other aspects in a writers life. The day was filled with seminars on agents, developmental and copy editing, and literary citizenship. The latter was and is, to me, deeply interesting. I've previously written here about one of my MFA colleagues -- Allie Marini Batts -- and I want to properly celebrate her both as a writer and as a champion for vibrant literary communities. She is so prolific in her writing, and so passionate about wholeheartedly participating in the community, that it is difficult to know what link to provide. Here is a start. Allie is receiving her degree this term, and as a graduating student presented a twenty minute lecture at this residency. She could have discussed any aspect of poetry, fiction, and nonfiction writing, but, not surprisingly, instead delivered a passionate and well-prepared lecture on the imperative need, if we are to be writers in the world, for us all to read, buy, and promote other writers. We need to write, yes, but we need, desperately, to read. To encourage others. To connect. The act of writing is a solitary activity, but writing is not a one-way relationship. A writer needs readers. Readers need writers. Like in issues of craft, I believe authenticity is also the number one key to good literary citizenship. We must read what we like to read. Connect with other authors with whom we feel a connection. Frequent bookstores that we love. This is not high school, and there is no room for ego in a discussion of authentic relationships. We must applaud writing that moves us, send out links to our friends when we are touched, write letters of support to authors whose essays strike us in one way or another. In this day of online communication and social networking, we must go beyond our isolated laptop. While reading writers that we admire, we ourselves improve. And by reaching out to them, we begin to weave a web of interconnection of support, encouragement, growth. Yesterday was Meltdown Monday.

It was exactly the way it plays out in movies about high school when the list of who made the team or the spring play gets posted in the hallway. The hopefuls crowd around the post, straining their necks to see around their classmates. There are high fives and tears, celebrations and breakdowns. The equivalent here is the mentor selection. The list is taped to the wall outside the Program Office at 1pm. I actually missed the crowd since my seminar didn't get out until 2:30. I thought of sneaking out "to the bathroom", but skipping out of class or needing to hear news at the very moment it breaks is not my style. So at 1pm, I simply glanced at the clock on the wall and then turned my attention back to the discussion. At 2:34pm I read the news that I was selected to study with one of my top choices for mentor this semester. I got what I wanted. And then I proceeded to have a complete meltdown. As my eyes scanned the list once, then twice, I felt my mood plummet. There were some compounding circumstances having to do with almost no sleep since last Wednesday, low blood sugar, and a poorly made salad at the little sandwich shop here on campus. It's all ridiculous, really. There's no place I'd rather be than here, now, and the mentor I was assigned to is exactly the person I had been hoping for since attending her seminar and reading last semester. So, this is what it's like at a low residency MFA program. Months and months of silence, working alone, feeling disconnected to my fellow students between the monthly reading conferences. Reading reading reading, writing writing writing. And then an intense two weeks of running ragged, pressing inspiration and ideas into my mind like flower petals, hoping their vibrancy will linger at least until I have a chance to re-type my notes. Just now, on my way into the lounge to jot down these thoughts, I passed a colleague in the courtyard. She was resting on a bench under the stand of sequoias, reading. She offered a seat for me, but I was on my way here to write. I know how comforting the sequoias are. I know how peaceful I feel in the moments I steal to be outside in the soft breeze of the natural world. And yet I choose each morning to hole up in this fluorescent lit room, staring at my MacBook screen, typing out my moods and thoughts about the day before. I know how to nurture myself, and yet I put it aside because I am hungry to grow, thirsting to develop this craft, yearning to write in a way that reaches deep down through muck and pull up gems, to write in a way that heals my personal hurts while touching someone else, helping them to heal. When I teach yoga, I end every class with the same prayer: May I be at peace. May my heart remain open. May I know the beauty of my own true nature. May I be healed. May I be a source of healing in the world. It is a question of balance, and sometime balance does not mean standing on both feet. It means wobbling, leaning far out to the side, getting knocked off my center, and then finding my way back. I want to grow, and so need to reach beyond my normal range. Later, next week, I'll catch up on sleep, eat well, get to my yoga mat, go for a run at the park, and find my way back to normal. This, at least for me, is the beauty of my own true nature. I go out on limbs; I sometimes melt. May I be at peace. |

Archives

May 2019

Categories

All

|